2024/10 “Vietnam-U.S. Security Cooperation Prospects under the Comprehensive Strategic Partnership” by Phan Xuan Dung and Hoai Vu

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

- In the past decade, Vietnam and the United States have incrementally strengthened security cooperation across various areas, including maritime security, defence sales, search and rescue, humanitarian and disaster relief, war legacy issues, and peacekeeping.

- Hanoi and Washington have pledged to enhance and broaden their security relations under the recently established comprehensive strategic partnership (CSP).

- Several conducive factors support the advancement of Vietnam-U.S. security cooperation in the upcoming years. These include growing strategic convergence, a deepening network of shared defence partners, and Vietnam’s military modernization efforts.

- However, sudden leaps or dramatic breakthroughs in Vietnam-U.S. security cooperation are unlikely due to certain constraints. These include Vietnam’s cautious approach, defence cooperation not being the top priority under the CSP, defence interoperability gaps, and lingering trust deficits.

- Therefore, despite the recent upgrade in diplomatic status, Vietnam-U.S. security cooperation has not reached a new level. Nonetheless, expanded defence collaboration in soft areas could help overcome some of the existing constraints and advance mutual strategic interests.

* Phan Xuan Dung is Research Officer in the Vietnam Studies Programme of the ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute. Hoai Vu is Research Assistant at the Institute for Foreign Policy and Strategic Studies under the Diplomatic Academy of Vietnam.

ISEAS Perspective 2024/10, 6 February 2024

INTRODUCTION

Since establishing a ‘comprehensive partnership’ in 2013, Vietnam and the United States have incrementally expanded their security relations, a domain that was hitherto sensitive and limited in scope. In 2015, the two countries adopted the Vietnam-U.S. Joint Vision Statement on Defence Cooperation, which codified activities already undertaken under the 2011 Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) on Advancing Bilateral Defence Cooperation.[1] Vietnam and the U.S. also engage in two dialogue mechanisms — the Political, Security, and Defence Dialogue and the Defence Policy Dialogue. Guided by these bilateral frameworks, Vietnam-U.S. security cooperation has progressed significantly across various areas, including maritime security, defence sales, search and rescue (SAR), humanitarian assistance and disaster relief (HADR), war legacy issues and peacekeeping.

Despite these remarkable strides, Vietnam-U.S. security cooperation remains at a low level, and primarily involves soft forms of engagement.[2] The recent upgrade of bilateral ties to a comprehensive strategic partnership (CSP) raises the question of whether this will change.

This article examines the recent progress in Vietnam-U.S. security cooperation and discusses its prospects under the CSP. It argues that given the current facilitators and constraints, the two countries will continue to advance defence collaboration at a measured pace, focusing on areas of low sensitivity.

RECENT PROGRESS IN VIETNAM-U.S. SECURITY COOPERATION

Maritime Security and Defence Articles

Maritime security and defence articles are key components in Vietnam-U.S. growing defence links. From 2017 to 2023, the U.S. State Department granted Vietnam approximately US$104 million in security assistance through the Foreign Military Financing (FMF) programme, aiming to bolster Vietnam’s maritime security and law enforcement capabilities.[3] Additionally, Vietnam received a separate US$81.5 million from FMF in 2018 as part of the U.S. Indo-Pacific Strategy.

A notable aspect of bilateral maritime security cooperation is U.S. port calls to Vietnam and joint naval exercises. After Vietnam opened the Cam Ranh Bay Military Port to all foreign naval vessels in 2010, the USNS Richard Byrd transport ship became the first to use the port’s logistical services in 2011.[4] Since then, U.S. ships have docked at the port for logistics and maintenance services almost every year. Three U.S. aircraft carriers — USS Carl Vison, USS Theodore Roosevelt, and USS Ronald Reagan — made port calls and held exchange activities in Vietnam in 2018, 2020 and 2023, respectively. Several U.S. naval vessels have visited Vietnamese ports and conducted non-combatant drills known as Naval Engagement Activity (NEA), with the Vietnam People’s Navy. The latest iteration of NEA, conducted in 2017, focused on diving, search and rescue operations, and undersea medicine.[5] Moreover, since 2016, Vietnam has participated in U.S.-led multilateral maritime exercises, including the Southeast Asian Maritime Law Enforcement Initiative (SEAMLE), the ASEAN-U.S. Maritime Exercise, and the Rim of the Pacific Exercise (RIMPAC).[6]

The U.S. fully lifted its lethal arms embargo on Vietnam in 2016, enabling Vietnam to procure U.S. equipment to modernize its military. From 2016 to 2021, the U.S. authorized the permanent export of more than US$29.8 million in defence articles to Vietnam.[7] The U.S. Defence Department’s active Foreign Military Sales with Vietnam has also surpassed US$118 million. Key U.S. arms transfer to Vietnam includes the handover of two decommissioned Hamilton-class cutters, currently the largest cutters in the Vietnam Coast Guard (VCG). In 2023, the U.S. promised the delivery of the third one,[8] making Vietnam and the Philippines the only countries to receive three U.S. Hamilton-class cutters (other recipients have received either one or two).[9] The U.S. has also supplied the VCG with six Boeing Insitu ScanEagle tactical drones and 24 Metal Shark patrol boats.[10] Additionally, Vietnam has bought 12 Beechcraft T-6 Texan II trainer planes as part of a package that comes with logistical and technical support.[11]

SAR and HADR

Given Vietnam’s vulnerability to natural disasters and climate change impacts, enhancing disaster preparedness and recovery capabilities is crucial. Thus, cooperation with the U.S. in SAR and HADR activities plays a vital role in augmenting Vietnam’s security. In 2014, the USS John S. McCain conducted a SAR exercise with the VPN off the coast of Da Nang as part of its NEA with Vietnam.[12] This marked the first SAR training activity between the two navies. Subsequent NEAs also included exercises on SAR and HADR. In 2016, the two countries signed a letter of intent to form a working group to explore the possibility of storing supplies in Vietnam for HADR purposes.[13] Vietnam has also participated in multilateral cooperation projects on HADR and joint HADR exercises under the Pacific Partnership and Pacific Angel engagements.

War Legacy Issues

Collaboration to address the consequences of the Vietnam War, including unexploded ordnance (UXO), Agent Orange, and soldiers missing in action (MIA), continues to serve as the foundation of Vietnam-U.S. defence relations. The U.S. has provided over US$230 million for UXO mitigation efforts in Vietnam.[14] In 2018, the two governments celebrated the completion of the six-year joint dioxin remediation project in Da Nang. A year later, joint cleanup efforts commenced at Bien Hoa Air Base, the largest remaining dioxin hotspot in Vietnam. The U.S. government’s financial contribution for this project currently stands at US$218 million, including US$90 million from the U.S. Defense Department.[15] In addition, as of 2023, the U.S. has provided US$139 million to fund health programmes that support Vietnamese with disabilities linked to Agent Orange exposure.[16] Regarding the search for American MIAs, as of June 2023, 151 unilateral and joint remains evacuation missions have been conducted, leading to the repatriation of the remains of 734 American soldiers.[17] In 2021, Washington officially began assisting Hanoi in identifying the remains of Vietnamese MIAs through a programme funded by the U.S. Defense Department.[18] Since then, the U.S. has provided Vietnam with more than 30 sets of documents related to Vietnamese MIAs, along with many war artifacts.[19]

Peacekeeping

In recent years, Vietnam has actively participated in United Nations peacekeeping missions, with support from several partners, including the U.S. In 2015, the two countries signed an MOU on peacekeeping, cementing their cooperation in experience sharing, personnel training, technical assistance, equipment, and infrastructure support.[20] Such cooperation lays the groundwork for future bilateral cooperation on peacekeeping missions. Under the Global Peace Operations Initiative (GPOI), the U.S. has spent US$10.87 million to support Vietnam’s peacekeeping contributions, including the deployment of a level-2 field hospital to the UN Mission to South Sudan in 2018.[21]

VIETNAM-US SECURITY COOPERATION UNDER THE CSP: FACILITATORS AND CONSTRAINTS

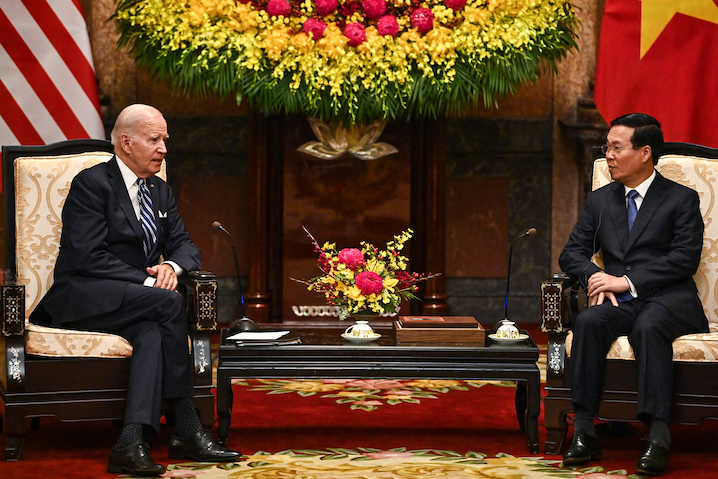

Over the past decade, Vietnam-U.S. security cooperation has witnessed substantial growth under the comprehensive partnership. This positive trajectory is expected to continue under the CSP established during President Joe Biden’s visit to Hanoi in September 2023. The joint leaders’ statement on the Vietnam-U.S. CSP reaffirms continued cooperation on maritime security, SAR, HADR, war legacy issues, and peacekeeping operations.[22] On defence industry and trade cooperation, the statement underscores the U.S. commitment to assist Vietnam in developing self-reliant defence capabilities. A new development is the establishment of a Law Enforcement and Security Dialogue between relevant law enforcement, security, and intelligence agencies.[23]

This section discusses the facilitators and constraints that will shape Vietnam-U.S. security cooperation under the CSP in the upcoming years.

Facilitators

First, the two countries share growing strategic convergence, aligning on key bilateral and regional security issues. As stated in the joint statement on the CSP, the U.S. supports a strong, independent, self-reliant, and prosperous Vietnam in safeguarding its sovereignty and territorial integrity.[24] Regionally, the U.S. envisions a unified and robust ASEAN where Vietnam plays an active role in promoting the group’s centrality in addressing regional security issues. The joint statement also reiterates the two countries’ mutual interests in promoting freedom of navigation and upholding international law in the South China Sea. Moreover, the importance of Vietnam’s geostrategic position in the U.S. Indo-Pacific strategy has been increasingly stressed by U.S. officials and U.S. national security documents.[25] This underscores Washington’s commitment to work with Hanoi in promoting a shared vision of regional security.

Second, Vietnam-U.S. security cooperation stands to benefit from a deepening network of shared defence partners. Vietnam has been strengthening bilateral ties with key U.S. allies and partners in Asia, many of which are its comprehensive strategic partners (India, Japan, South Korea) or soon-to-be comprehensive strategic partners (Australia,[26] Indonesia,[27] Singapore,[28] and Thailand[29]). In 2022, ASEAN also upgraded its relations with the U.S. to a CSP, paving the way for new maritime and defence initiatives.[30] These developments position Vietnam and the U.S. to expand the scope of their defence cooperation, particularly on maritime security and peacekeeping, under trilateral, quadrilateral, and multilateral frameworks.[31]

Third, Vietnam’s military modernization efforts present opportunities for further collaboration on defence articles and technology. After the 13th Party Congress in 2021, Vietnam approved a plan to build a streamlined and strong army by 2025 and a revolutionary, regular, elite, and modern army by 2030.[32] Vietnam has also strived to diversify its arms imports and boost domestic defence production capabilities to become more self-sufficient. The U.S. is recognized as a key partner in these efforts. This was made evident in the presence of several major American defence firms at Vietnam’s first international defence expo in December 2022. U.S. Ambassador to Vietnam, Marc Knapper, said that the event “represents a new stage in Vietnam’s efforts to globalize, diversify, and modernize, and the United States wants to be part of it.”[33] Indeed, following the expo, Lockheed Martin, Boeing, Raytheon, and Textron reportedly held discussions with top Vietnamese government officials regarding the possible sales of helicopters and drones to Vietnam.[34]

Constraints

Despite these conducive factors, sudden leaps or dramatic breakthroughs in Vietnam-U.S. security cooperation are unlikely due to several constraints.

The first is Vietnam’s cautious approach to deepening ties with the U.S. in order to avoid negative reactions from China. Despite concerns over China’s maritime ambitions, Hanoi prioritises maintaining a stable and peaceful relationship with its northern neighbour. China might feel threatened by bolstered Vietnam-U.S. defence ties and respond with punitive actions against Vietnam. Thus, Hanoi has made efforts to reassure Beijing that its CSP with Washington is not an anti-China security pact. During recent Vietnam-China high-level meetings that occurred around the upgrade, Vietnamese leaders repeatedly reaffirmed positive bilateral ties with China and Vietnam’s ‘four nos’ defence policy.[35] Notably, Vietnam hosted President Xi Jinping in December 2023, just three months after Biden’s visit. On this occasion, Vietnam elevated ties with China by establishing a “community of a shared future”,[36] seemingly to balance the upgrade with the U.S.

Given its sensitivities to rising tension between the two great powers, Vietnam might scale back on joint naval activities and military training with the U.S. to keep a low profile. This could explain why Vietnam cancelled 15 defence engagement activities with the U.S. in 2019[37] and did not participate in RIMPAC in 2022, despite having participated in 2018.[38] Vietnam will also be hesitant to engage in combat military exercises with the U.S. in the South China Sea.

A second related constraint is that defence cooperation is not the top priority under the CSP. In the joint statement on CSP, economic and technological cooperation are clearly the main focus, while defence and security ties receive less attention. Moreover, the statement leans towards non-traditional security issues that the two countries have already been collaborating on.

This makes sense as Vietnam’s primary motivation for seeking a CSP with the U.S. was not defence needs. The upgrade aligned with Vietnam’s desire to create a robust and diverse network of strategic partners to ensure three key long-term objectives — security, prosperity, and international status. While the U.S. is seen as an important partner in all three aspects, Vietnam currently emphasizes economic development goals.[39] Hence, for Vietnam, the CSP is more about economics than defence and security.[40]

Washington initially expected that a strategic partnership with Hanoi would result in stronger bilateral defence ties to counter Beijing’s maritime ambitions. However, leading up to the establishment of the CSP, the U.S. had progressively understood that Vietnam would not be comfortable with making the CSP all about defence and security. In various official and unofficial exchanges, U.S. officials and scholars recognized Vietnam’s delicate approach, as well as the need for more patience on the U.S. side.[41]

The third constraint are the defence interoperability gaps between Vietnamese and American forces. A major obstacle is the language barrier. Proficiency in English is still a challenge for the Vietnamese military, and few American personnel can speak Vietnamese.[42] Another obstacle is the low level of cooperation on defence sales, exemplified by Vietnam’s limited import of U.S. weapons. Some scholars have suggested that Vietnam could elevate bilateral defence ties with the U.S. by concluding large-scale arms deals.[43] However, since the lifting of the U.S. arms embargo in 2016, no such deal has transpired. The U.S. is reportedly in talks with Vietnam on the possible sale of F-16 fighter jets.[44] Vietnam has yet to confirm this information, and the deal might not materialize. In the past, Vietnam has shown reluctance to buy major U.S. weapons, such as a second-hand F-16 fighter jet and a P-3C Orion maritime patrol aircraft.[45] Hanoi worried that purchasing major offensive weapons from the U.S. could irk Beijing, especially after the high-profile CSP upgrade. Moreover, there are interoperability concerns over Vietnam’s limited capacity to acquire and integrate U.S. military technology. These include high costs, a steep learning curve, and incompatibility with Russian-made equipment, which currently forms the majority of Vietnam’s weapon systems.[46]

Last but not least, trust deficits between the two countries remain. Despite the increased U.S. recognition of Vietnam’s one-party state system, political differences could still impede defence cooperation. In particular, Hanoi fears that the U.S. Congress might reject equipment sales due to concerns over human rights conditions in Vietnam.[47] Divergent stances on the Russian-Ukraine war, along with Vietnam’s continued reliance on Russia for major arms supplies, also hinder greater strategic trust. Vietnam is cognizant of potential sanctions under the U.S. Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act for buying Russian weapons.[48] Finally, Hanoi has reasons to doubt Washington’s commitments to the region in the upcoming years, given the U.S. ongoing preoccupation with conflicts in Europe and the Middle East.

CONCLUSION

Despite the recent upgrade in diplomatic status, Vietnam-U.S. security cooperation has not reached a new level. Instead, bilateral military relations will continue to concentrate on areas of low sensitivity, including maritime law enforcement, SAR, HADR, war legacy issues, and peacekeeping. Nonetheless, expanding collaboration in these fields could mitigate some of the existing constraints in Vietnam-U.S. defence ties and advance mutual strategic interests.

The US should provide more funding and equipment for Vietnam to enhance its self-reliant defence capabilities, as stated in the CSP. However, it is imperative that the U.S. consider Vietnam’s post-upgrade sensitivities and refrain from pushing for large-scale arms trade that could alarm China. The priority should be to help Vietnam modernize the VCG and improve its maritime domain awareness through equipment transfers and technical assistance. This serves the mutual interests of both countries by promoting freedom of navigation and upholding international law in the South China Sea.

In addition, boosting education and training for Vietnamese military officers will help bridge interoperability gaps between US and Vietnamese military forces. This could include more opportunities for Vietnamese officers to join English language training programmes and study in U.S. institutions. The U.S. should also invite Vietnam to join more non-combat bilateral and multilateral naval exercises. This will foster professional and operational relations between the two countries and with other defence partners.

Finally, increased U.S. efforts to address Agent Orange and UXO, as well as assisting Vietnam in the search for its MIAs, can play an important role in reducing trust deficits. Vietnamese leaders have consistently indicated that greater U.S. efforts to address war consequences are a prerequisite for bilateral cooperation in other areas.[49]

ENDNOTES

For endnotes, please refer to the original pdf document.

| ISEAS Perspective is published electronically by: ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute 30 Heng Mui Keng Terrace Singapore 119614 Main Tel: (65) 6778 0955 Main Fax: (65) 6778 1735 Get Involved with ISEAS. Please click here: /support/get-involved-with-iseas/ | ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute accepts no responsibility for facts presented and views expressed. Responsibility rests exclusively with the individual author or authors. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form without permission. © Copyright is held by the author or authors of each article. | Editorial Chairman: Choi Shing Kwok Editorial Advisor: Tan Chin Tiong Editorial Committee: Terence Chong, Cassey Lee, Norshahril Saat, and Hoang Thi Ha Managing Editor: Ooi Kee Beng Editors: William Choong, Lee Poh Onn, Lee Sue-Ann, and Ng Kah Meng Comments are welcome and may be sent to the author(s). |

2024/9 “Advancing the ASEAN Outlook on the Indo-Pacific Beyond Indonesia’s Chairmanship” by Joanne Lin

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

- Indonesia’s Chairmanship in 2023 has advanced the AOIP’s implementation through tangible projects and activities, thereby elevating the AOIP as a pivotal platform for promoting ASEAN’s central role.

- Beyond Indonesia’s Chairmanship, ASEAN needs to prioritise a consistent and impactful implementation of the AOIP across successive Chairmanships. This is essential to solidify the AOIP’s standing as a strategic document to reinforce ASEAN’s central role in the region.

- To advance the AOIP and ensure its ongoing strategic relevance, ASEAN can adopt some key strategies. These include assuming a leadership role in implementation, formulating a multi-year work plan, maintaining a commitment to quality-focused approaches, transforming bilateral activities into regional projects, and establishing a dedicated fund.

- While the AOIP alone may not fully address escalating strategic competition, leveraging ASEAN-led mechanisms for its implementation positions the organisation as a “bridge-builder”. This role allows ASEAN to actively contribute to inclusive multilateral solutions, and foster dialogue and cooperation among regional powers.

* Joanne Lin is Co-coordinator of the ASEAN Studies Centre at ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute, and Lead Researcher (Political-Security) at the Centre.

ISEAS Perspective 2024/9, 2 February 2024

INTRODUCTION

ASEAN embraced the ASEAN Outlook on the Indo-Pacific (AOIP)[1] in 2019 as a strategic response to escalating geopolitical tensions[2] and the growing influence of major powers in the region. The Outlook reflects ASEAN’s commitment to maintaining its centrality and leading role in the region by promoting its mechanisms and adhering to key principles such as inclusivity, openness, and a rules-based framework.

Specifically, the Outlook aims to foster practical and tangible cooperation with ASEAN’s external partners in four key areas: maritime cooperation, economic, connectivity, and sustainable development. Despite Indonesia’s advocacy and support from ASEAN’s dialogue partners, the initial implementation faced criticism for its sluggish progress and perceived lack of concrete initiatives during the first four years.

Apart from discussions and sporadic activities[3] with dialogue partners, there was no course of action for the implementation of the AOIP until November 2022, when ASEAN leaders adopted the Declaration on Mainstreaming Four Priority Areas of The ASEAN Outlook on The Indo-Pacific within ASEAN-Led Mechanisms.[4] The declaration acknowledged the need for collective leadership with ASEAN to proactively address emerging challenges in the region. It also endorsed a List of Criteria on Mainstreaming the AOIP (an internal document) to implement the four priority areas of the AOIP through ASEAN-led mechanisms such as the ASEAN Plus-One, ASEAN Plus Three (APT), East Asia Summit (EAS), the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF) and the ASEAN Defence Ministers’ Meeting Plus (ADMM-Plus).

This development helped set the stage for Indonesia’s Chairmanship in 2023 to advance AOIP’s implementation through tangible projects and activities. A notable achievement was the inaugural ASEAN Indo-Pacific Forum in September 2023[5] focusing on green infrastructure and resilient supply chains, sustainable and innovative financing, digital transformation and the creative economy. The Forum brought together ASEAN member states and external partners and reportedly identified 93 cooperation projects worth US$38.2 billion, with an additional 73 potential projects amounting to US$17.8 billion.[6]

For the first time since the AOIP’s adoption, the initiative seems to yield tangible benefits to the region, attracting new commitments by ASEAN’s external partners. As a result, regional leaders increasingly recognise the AOIP as a pivotal platform for promoting ASEAN’s central role and mechanisms.[7] The initiative has also been praised by Singapore Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong, who commended it for being “omnidirectional and inclusive”.[8]

Despite the success of the Forum, questions linger regarding the AOIP’s effectiveness in shaping the regional architecture as well as in addressing current and future geostrategic challenges. There are also uncertainties in the prospect of advancing the AOIP beyond Indonesia’s Chairmanship. This Perspective addresses these questions and explores potential strategies for ASEAN to ensure the continued relevance and successful implementation of the AOIP across all chairmanships.

ASSESSING THE IMPACT AND LIMITATIONS OF THE AOIP

Despite its lack of a strategic dimension, the AOIP has been deemed successful in securing buy-ins from ASEAN’s external partners, mainly owing to its mild and apolitical nature, and for focusing on cooperation rather than rivalry.[9] The document’s neutrality (which differs from most Indo-Pacific strategies) makes it possible for most countries to accept the AOIP’s values and cooperation.

The overwhelming support from ASEAN’s dialogue and external partners, including China (a target of various Indo-Pacific strategies) has led to an increasing recognition of the AOIP’s benefits by more ASEAN countries. Currently, seven dialogue partners, namely India, Japan, the US, Australia, China, the Republic of Korea (ROK) and New Zealand have issued standalone statements with ASEAN regarding AOIP cooperation. While Canada and the EU have not issued separate statements, they have incorporated similar language in joint leaders’ statements with ASEAN. This has therefore enabled ASEAN to be a norm-setter and to play a leading role in the Indo-Pacific.

Beyond dialogue partners, most other external partners of ASEAN have committed to various forms of concrete cooperation across AOIP’s priority areas, enhancing the prospects for sustained implementation and for more partners in the long run.

While the AOIP has increased ASEAN’s standing in the regional architecture through the support of external partners, its strategic impact in addressing or mitigating the negative consequences of major power strategic competition in the region remains in question.

Despite garnering support from ASEAN’s partners, the AOIP’s lack of a strategic thrust hampers its ability to effectively manage external threats, particularly those posed by China. The inclusive nature of the AOIP makes it challenging for ASEAN to be viewed as a “like-minded” partner by countries that have a vested interest in the Indo-Pacific, such as the US, Japan, Australia and India (QUAD members), as well as countries such as the ROK, UK, Canada, France and Germany. This is especially so when ASEAN refuses to speak out against China for its aggression in regional flashpoints such as the South China Sea and the Taiwan Strait.

Essentially, the AOIP’s limited strategic perspective and its absence of a hard power component constrain its efficacy in addressing conflicts. Apart from preventive diplomacy, it is unable to deter security threats or provide a strategic balance[10] in the region. This has prompted Indonesia’s former Foreign Minister Marty Natalegawa to claim that the AOIP was more of a defensive and programmatic approach than a bold one seeking to actively confront geopolitical challenges.[11]

The proliferation of non-ASEAN security groupings like the QUAD and AUKUS demonstrate that ASEAN-led initiatives such as the AOIP may not adequately meet the region’s security needs. Opinion polls, as reflected in surveys like the State of Southeast Asia Survey reports,[12] suggest that major powers’ security initiatives may weaken ASEAN’s centrality, despite their rhetorical support for the AOIP and ASEAN centrality.

Although there is increasing interest for ASEAN to take on a greater responsibility in managing major power rivalries, the region is far from being a provider of regional security.[13] Notwithstanding the AOIP being created to address geostrategic tensions, the defence sector, in particular, has been hesitant to adopt the Indo-Pacific concept. The ASEAN Defence Ministers’ Meeting (ADMM) has only recently adopted a concept paper on the implementation of the AOIP from a defence perspective,[14] four years after the AOIP was published. Moreover, despite the expansive scope of maritime cooperation, the ADMM can only approve one AOIP activity each year and the activity should be one-off and informal in nature – signalling a lack of enthusiasm to mainstream the AOIP in the defence sector.

As such, under Indonesia’s leadership, the AOIP’s implementation has focused on softer cooperation and easier objectives like green infrastructure, digital developments, sustainable development, and the promotion of trade and investment.

This has led some observers to argue that the AOIP primarily symbolises the group’s aspirations rather than offering a concrete pathway to achieve specific outcomes.[15] Therefore, the Outlook may only be sufficient to kickstart and support more processes, dialogues, and lower-hanging cooperation rather than achieving tangible strategic outcomes, particularly those pertaining to security.

AOIP’S IMPLEMENTATION BEYOND INDONESIA’S CHAIRMANSHIP

The significant advancement of the AOIP’s implementation in 2023 was not surprising. Indonesia’s fervent push for extensive implementation was notably in line with President Joko Widodo’s priority of establishing the country as a Global Maritime Fulcrum. However, the enthusiasm for the AOIP’s continued progress beyond Indonesia’s Chairmanship remains uncertain.

During the early stages of formulating this Outlook, ASEAN countries were not unified in their perspectives on the narratives surrounding the Indo-Pacific or their level of support for the concept.[16] As such, despite the ultimate endorsement of the AOIP by all ASEAN countries, one of the significant challenges in its implementation is the varying degree of ownership among the member countries, along with their willingness and ability to allocate resources for its implementation.

Encouragingly, the AOIP is gradually becoming internalised within ASEAN as an instrument that brings tangible benefits to the grouping. As noted in the ASEAN Leaders’ Declaration on ASEAN As an Epicentrum of Growth[17] adopted in September 2023, ASEAN leaders have committed to further efforts in operationalising the AOIP by expediting AOIP projects and activities initiated by ASEAN or jointly with external partners, and to support the list of concrete projects identified at the inaugural ASEAN-Indo-Pacific Forum[18].

The Foreign Minister of Laos as the Chair of ASEAN in 2024 has given the reassurance that Laos will continue the implementation of ASEAN’s initiatives, including the AOIP.[19] Similar to Indonesia’s priorities in 2023, it is expected that Laos will strengthen the connectivity and sustainable development aspects of the AOIP by focusing on integrating and connecting economies, digital transformation, and climate change resilience.[20] Additionally, the Secretary-General of ASEAN Kao Kim Hourn has expressed hope that Laos might consider convening the 2nd ASEAN-Indo-Pacific Forum this year, with a theme that is in line with Laos’ Chairmanship priorities.

Importantly, Indonesia’s efforts in pushing for the mainstreaming of the AOIP has resulted in some level of institutionalisation through the creation of processes such as the “List of Criteria on Mainstreaming the AOIP”. Systematic processes have been put in place to identify, evaluate, track and monitor programmes, projects and activities under the AOIP undertaken by the ASEAN Secretariat. This form of tracking is expected to persist across Chairmanships, irrespective of the levels of motivation and aspiration that each Chair may have towards the Indo-Pacific and the Outlook. Overall, these developments suggest a growing recognition of the AOIP’s significance within ASEAN.

POTENTIAL STRATEGIES IN ADVANCING THE AOIP

In advancing the implementation of the AOIP, ASEAN may consider the following strategies. Firstly, a multi-year work plan encompassing a list of activities is crucial for maintaining a consistent trajectory of progress and ensuring a more impactful implementation. While external partners may propose recommendations for joint activities, ASEAN should also assess its own needs to prioritise specific areas of cooperation to align with frameworks such as the ASEAN Maritime Outlook (AMO),[21] which can offer a clearer direction for ASEAN’s maritime efforts in the Indo-Pacific.[22]

Secondly, to reinforce ASEAN centrality, the grouping should take the lead in proposing programmes and projects under the AOIP that will contribute to ASEAN community building and meet sectoral bodies’ priorities. ASEAN should identify the most appropriate partners to implement specific projects based on the strength of each country. ASEAN should also ensure synergies in the activities across ASEAN-led mechanisms. This approach will prevent overlaps in activities or workshops proposed by external partners for a more streamlined implementation.

Thirdly, the identification of AOIP initiatives should involve meaningful efforts rather than a mere re-packaging of existing cooperation under various Plans of Action. ASEAN should focus on innovative initiatives that can enhance AOIP’s strategic value across ASEAN-led mechanisms including the EAS, ADMM-Plus, and the ARF, prioritising quality over quantity. Quantity-focused approaches may lead to competition among dialogue partners and undermine the strategic essence of the AOIP. ASEAN should shift its focus from an obsession with numbers or statistics to activities that yield not only output but meaningful outcomes that can increase its members’ capabilities in a strategic competition.

Fourthly, although ASEAN has identified an extensive list of concrete projects, predominantly of a bilateral nature, as seen at the inaugural ASEAN-Indo-Pacific Forum, there is a crucial need to transform these isolated initiatives into cohesive ASEAN strategic objectives. The transformation can be achieved through the process of “connecting the connectivities”[23] or fostering collaboration and knowledge-sharing among member states to produce innovative projects. Moving forward, a concerted effort should be made to ensure that AOIP projects or activities deliver benefits to as many ASEAN member states as possible, thereby solidifying their status as true “ASEAN” initiatives.

Lastly, there is a pressing need to establish a dedicated fund to implement AOIP activities. This will allow ASEAN to rely more on internal funding for its neutrality and centrality, and to assert more control over its priorities. While cooperation with external partners should persist, having an independent funding mechanism will let ASEAN determine the nature and execution of projects. Furthermore, this will ease the burden of the current and future Chairs in organising larger-scale events such as the ASEAN-Indo-Pacific Forum, and provide more incentives for them to host more such activities.

CONCLUSION

The AOIP has experienced significant success during the Indonesia Chairmanship. However, achieving consistent and impactful implementation of the AOIP across successive Chairmanships is imperative to solidify the Outlook as a strategic document that can bolster ASEAN’s central role. The analysis above highlights crucial factors for ensuring AOIP’s success, emphasising the importance of ASEAN’s leadership, developing a multi-year work plan, ensuring commitment to quality-focused approaches, transforming bilateral activities into regional projects, and establishing a dedicated fund. These will not only foster a sustained momentum in advancing the AOIP but also ensure its strategic relevance.

The analysis also underscores that relying solely on the AOIP may prove inadequate in addressing the rising strategic competition and the multitudes of initiatives led by major powers. However, leveraging ASEAN-led mechanisms, particularly the EAS (the region’s premier leaders-led forum) in the implementation of the AOIP, has the potential to position ASEAN as a pivotal “bridge-builder”. Secretary-General of the United Nations Antonio Guterres has emphasised ASEAN’s crucial role in ‘building bridges of understanding’ and advancing multilateral solutions.[24] This approach empowers ASEAN to facilitate extensive dialogue among regional powers and foster interactions between countries like China and the US. Furthermore, it allows ASEAN to actively contribute to shaping guiding principles and norms, advocating for multilateralism, and working towards a more inclusive regional architecture.

ENDNOTES

For endnotes, please refer to the original pdf document.

| ISEAS Perspective is published electronically by: ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute 30 Heng Mui Keng Terrace Singapore 119614 Main Tel: (65) 6778 0955 Main Fax: (65) 6778 1735 Get Involved with ISEAS. Please click here: /support/get-involved-with-iseas/ | ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute accepts no responsibility for facts presented and views expressed. Responsibility rests exclusively with the individual author or authors. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form without permission. © Copyright is held by the author or authors of each article. | Editorial Chairman: Choi Shing Kwok Editorial Advisor: Tan Chin Tiong Editorial Committee: Terence Chong, Cassey Lee, Norshahril Saat, and Hoang Thi Ha Managing Editor: Ooi Kee Beng Editors: William Choong, Lee Poh Onn, Lee Sue-Ann, and Ng Kah Meng Comments are welcome and may be sent to the author(s). |

Temasek Working Paper No. 7: 2024 – The Changing Fortunes of the Raja Negara and the Orang Laut of Singapore in the 18th Century by Benjamin J.Q. Khoo

2024/8 “Understanding Indonesia’s 2024 Presidential Elections: A New Polarisation Evolving” by Max Lane

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

- The coalition developing around the candidacy of Prabowo shows characteristics of being a regrouping of core elements from Suharto’s New Order. Incumbent President Joko Widodo is also supporting this coalition. One of Widodo’s sons is Prabowo’s vice-presidential running mate.

- While polls put Prabowo in the lead, scoring in the mid-40 percentages, support for him may nevertheless be stagnating.

- A polarisation is developing between this coalition and the other parties, especially the PDI-P, and some elements of civil society, especially the liberal media and students. This polarisation is connected to tensions between modes of politics: one strongly influenced by Suharto era cronyism and one connected to those disadvantaged for being outside that elite.

- A differentiation between an approach emphasising policy discussion and one emphasising rhetorical image-making has become sharper. This is paralleled by stronger criticism by the two other candidates, Anies Baswedan and Ganjar Pranowo, of Prabowo’s support for Widodo’s dynasty-building manoeuvres, his accumulation of wealth, and alleged mismanagement of the defence equipment procurement.

- As this polarisation is still in its early stages, it is not clear how significant it will be in the thinking of Indonesia’s 200 million voters. But while it develops, there is increasing potential for collaboration between the Baswedan and Pranowo camps, and more support from civil society for them.

ISEAS Perspective 2024/8, 31 January 2024

*Max Lane is Visiting Senior Fellow at ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute. He is the author of “An Introduction to the Politics of the Indonesian Union Movement” (ISEAS 2019) and the editor of “Continuity and Change after Indonesia’s Reforms: Contributions to an Ongoing Assessment” (ISEAS 2019). His newest book is “Indonesia Out of Exile: How Pramoedya’s Buru Quartet Killed a Dictatorship” (Penguin Random House, 2022).

INTRODUCTION

According to almost all recent polls, Indonesia’s Defence Minister Prabowo. Prabowo is the leading presidential candidate, scoring always over 40%[1] for “electability”. He has the support of the incumbent President, Joko Widodo, whose eldest son is Prabowo’s vice-presidential candidate and whose youngest son is chairperson of the fanatically pro-Prabowo Indonesian Solidarity Party (PSI). Prabowo also has the support of former two-term president Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, and prominent New Order military figure General Wiranto. There is also a kind of blessing from well-known members of the Suharto family, with Prabowo elevating his former wife, Titiek Suharto, to vice-chair of his party Gerindra’s Advisory Board.[2]

What is surprising is that despite all the support, his poll results less than a month out from the election on 14 February are considerably lower than those of candidate Widodo in the lead-up to the 2019 presidential election. At that time, Widodo was polling at over 50% with his opponent then, Prabowo, at 33%.[3] Today, even with Widodo’s and Yudhoyono’s ostensible support, Prabowo is scoring around 43%, up only 10% from 2019.

A NEW DIFFERENTIATION OR EVEN POLARISATION IN THE ELITE

The 20-year period after the fall of President Abdurrahman Wahid has been characterised by the theatre of rhetorical polarisation among the Indonesian political elite. Although there is still some time left for campaigning, the contestation between the three presidential candidates – Baswedan, Prabowo and Pranowo – is revealing new cleavages which may reframe Indonesia’s political life. On the other hand, a consensus over the fundamentals of the status quo, as defined by government policies of the last ten years, may see a relapse into the politics of unanimity.

There are two types of political differentiation being revealed in the current electoral process.

The first relates to the nature of the coalition formed in support of Prabowo. As indicated above, this coalition comprises many elements associated with the New Order. Apart from Prabowo, Yudhoyono and Wiranto, there is also former Coordinating Minister Luhut Panjaitan, Widodo’s business partner since at least 2008.[4] Another is General Moeldoko, former Commander of the Armed Forces between 2013-2015, who Widodo appointed his Chief of Staff. Also appearing is long-term Golkar figure and oligarch, Aburizal Bakrie, the Mentor of Prabowo’s campaign team. While Widodo successfully portrayed himself in 2013-2014 as a novelty from outside the New Order elite, this image was belied by his immediate appointment of Luhut as a de facto ‘prime minister’, who was assigned more than 14 crucial policy implementation tasks.[5] This was followed later by Widodo’s rapid appointment of Moeldoko as his Chief of Staff and then his total rapprochement with Prabowo. Prabowo further indicated the process of Widodo’s integration into this milieu. His association with figures from Suharto’s New Order was further emphasised when Golkar recently posted an AI-generated video of the long-dead Suharto speaking for the Prabowo campaign.[6]

While there are also big business supporters of both the Anies Baswedan and Ganjar Pranowo candidatures,[7] this combination of ex-generals, Golkar figures and the Suharto family exposes Prabowo’s coalition as harking back to the Suharto era’s New Order. There is even talk of Prabowo and Titiek Suharto remarrying to bring a Suharto back into the presidential palace.[8] The Baswedan coalition and the Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (PDI-P) both receive support from business figures who came into prominence during the New Order. Baswedan is supported by former Golkar figure and oligarch businessman, Surya Paloh. However, it can be argued that the latter supporters do not represent core New Order elements in the way that Prabowo’s coalition does.

The PDI-P itself, under the leadership of chairperson and former president Megawati Sukarnoputri, had opposed Suharto when he was moving towards a dynastic approach to politics. Suharto’s government intervened in the internal affairs of Megawati’s party to stop her from becoming its leader, and in 1998 Suharto appointed his daughter, Tutut, to the Cabinet in a clear attempt to pave the way for a dynastic succession.[9] For ten years, during the two presidential terms of Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, the PDI-P was outside of government. The party is not based on or embedded in cronyism with the oligarchs at the level of national government. During the two terms of Widodo’s presidency, Widodo prioritised positions for his own cronies, especially Luhut Panjaitan but also others such as the academic, Pratikno. In the process, PDI-P has been kept out of the most important business-linked ministries.[10]

Baswedan, as a politician and an academic prior to that, has not been embedded in any party or other institution. He courted the Democrat Party (PD) in 2013, then the PDI-P during Widodo’s 2014 campaign, and was nominated by the Justice and Welfare Party (PKS) and Gerindra when he stood for Governor of Jakarta in 2017, prior to being supported by the National Democratic Party (Nasdem) and the National Awakening Party (PKB), as well as the PKS for his presidential campaign now. This is the history of an ambitious politician, but one not embedded within the core of the elite coming out of the New Order.

This new polarisation between core New Order elite elements, now including Joko Widodo, and those outside has meant that the polarisation is creating concern beyond the political parties, among some elements of civil society. This is most visible in sections of the media – led by the liberal TEMPO magazine[11] – as well as human rights NGOs and students opposing the Prabowo-Gibran Rakabuming Raka (read: Widodo) camp. There are two reasons for these concerns. First is the use of Widodo’s incumbency to build a dynasty for his family, and second is the displayed impunity (Prabowo’s) for past human rights violations. The liberal media has led in expressing these worries, but in early January 2024, the first signs appeared of what may well become a student protest movement.[12]

This polarisation also envelopes the political parties. The Widodo-Prabowo camp has alienated the key party outside the New Order core, the PDI-P. Widodo and Prabowo owe their access to the national political stage to Megawati and her PDI-P.[13] For 2024, however, they have united to defeat the PDI-P’s candidate, Ganjar Pranowo. In Widodo’s case, the betrayal may be seen to have begun with the rapprochement with Prabowo in 2019, although Widodo kept up a semblance of loyalty to the PDI-P until 2023. The alienation from the PDI-P was underlined by Widodo’s absence at the party’s recent 51st anniversary celebrations while other major figures such as Vice-President Ma’ruf Amin, Finance Minister Sri Mulyani as well as Basuki Tjahaja Purnama (“Ahok”), now a member of the PDI-P, were in attendance. At this event, Megawati referred to all the ministers who attended as “those willing to attend”, an obvious implied sneer at Widodo who arranged to be overseas at this time.[14]

The alienation of the PDI-P by and from Prabowo and Widodo now aligns that party with the media and some civil society elements whose primary orientation is “Asal Bukan Prabowo” (Anybody but Prabowo) – a theme often reported as “trending”.[15] It should be noted that there are significant civil society elements who are not supporting any of the three presidential candidates. Even so, that alignment adds to the dynamic of polarisation.

The position of the Anies Baswedan campaign in this new polarisation is also clear, although its origins are different. Baswedan is now solidly situated as key to the opposition against Prabowo. Unravelling the nature of the oppositional relationship requires also considering the political culture of the New Order core. The basis for an alliance between the three parties – Nasdem, PKB and the Prosperous Justice Party (PKS) – may seem to be primarily opportunistic, although all three can claim to be outside of the New Order core. While Surya Paloh was a significant figure in Golkar in the last years of the New Order, his small Nasdem party has kept itself at arm’s length from the New Order elements. A prominent spokesperson for Nasdem in the current campaign is Surya Tjandra, who is historically associated with civil society criticism of the New Order. Tjandra was a human rights lawyer close to the trade unions until he joined the Indonesian Solidarity Party (PSI) in 2018, when it was still perceived as a party with a democratic ideology. He became a deputy minister (agrarian affairs and spatial planning) in Widodo’s Cabinet. Now, in Nasdem, he is campaigning for Baswedan as a candidate who can propound development and ideology against a purportedly hapless Prabowo on that score.[16]

Both through the televised presidential debates (12 December 2023 and 7 January 2024; 4 February forthcoming) as well as general campaigning, Baswedan presents himself as a candidate with deep ideas and who can explain the concepts involved. He is considered a technocratic intellectual. Symbolic of this approach, although not the only example of it, is Baswedan’s proposals for alternatives to a new national capital in Kalimantan, the latter being depicted as a glamour project, and at the same time pushing his team’s proposal for developing 40 other cities throughout Indonesia to a higher level.[17]

However, it is not so much the content of Baswedan’s policies that differentiates him from the Prabowo campaign but the very notion of a serious policy discussion. This contrasts totally with Prabowo’s strategy of creating a new image for himself as the “adorable grandpa” who can joget (dance), and spreading the message that politics should be “fun”.[18] His campaign has flooded social media with animations of the “adorable grandpa” in the form of a dancing Prabowo.[19] Running a election campaign as entertainment can be said to contain an element of “Jokowism”. Candidate Jokowi would use political rallies to entertain the crowd with quizzes, with prizes being given out to audience members who could answer simple questions.

Another key aspect of Baswedan’s campaign are the “desak Anies” (“Press Anies”) meetings where constituents are invited to press (question) Baswedan on any issue, face to face. This seems particularly popular among young people;[20] the sessions can be watched live on YouTube[21] and some excerpts can be viewed on TikTok.

This aspect of the polarisation – a technocratic vision for managing Indonesia versus the personalised character of Jokowi-ism and Prabowoism – came across in the third (second for the presidential aspirants) round of the televised debates on 7 January. Baswedan and Ganjar Pranowo critically questioned Prabowo on his implementation of policies as minister of defence, to which the latter reacted defensively.[22] Prabowo seemed not to be armed with the data needed to defend himself, lamenting afterward that he did not expect to be quizzed in this way. Almost ten years of rhetorical polarisation rather than real polarisation means he was equipped only with rhetoric, expressed sometimes with somewhat uncontrolled emotions.[23]

On 7 January, Baswedan tested Prabowo on issues underlying this polarisation, especially in relation to Widodo’s political dynasty-building. In an exchange on ethics, Baswedan asked Prabowo whether it was ethical for him to continue with his current vice-presidential running mate even after the Constitutional court process which cleared the way for Gibran to be nominated was judged to be ethically flawed. Prabowo reacted defensively and emotionally, declaring that Baswedan did not have the moral authority to talk about ethics.[24]

Baswedan also raised issues aimed at depicting Prabowo as being guilty of New Order style wrongdoing, including his alleged accumulation of 340,000 hectares of land – a figure disputed by Prabowo – and procurement of military equipment “using middle-men”, implying possible corruption.[25] This latter issue had been reported by TEMPO newsmagazine.[26]

Almost all polling following this debate rated Baswedan and Ganjar much higher that Prabowo in terms of performance.[27] Ganjar had clearly prepared himself to be technically well-informed, and his confident and combative interrogation of Prabowo saw some polls rating him the winner.[28] The debate went some ways towards contouring the differentiation between the candidates.

HOW WIDE IS THE NEW POLARISATION?

The 2014 and 2019 elections were marked by rhetorical rather than real polarisations.[29] The current polarisation is different in that it has a base in the legacy of the 32 years of the New Order, with its mode of governance built around dynastic power, cronyism, and a right to rule presumed by members of the New Order elite. This legacy is also characterised by the division between those integrated into that culture or hankering to be a part of it, and those excluded from it. Over time, the latter, as the consequence of different personal/political histories, have attained starkly different political outlooks.

Be that as it may, this new polarisation does not reflect fundamental variances based on basic economic or social divides. Rather it is a differentiation around mode of governance. Should governance be subordinated to personal ambition and dynasty-building or to the technocratic management of society and of its economic growth?

While this appears to be a genuine differentiation, it is important to note two factors. First, this differentiation is still in an early stage. Second, it is not yet clear to what extent this differentiation is important to the political players involved – especially the parties supporting Baswedan and Ganjar. It is no doubt a differentiation closely connected to Baswedan’s academic/intellectual background and ideology, but the dynamics go beyond that. Even the PDI-P, together with the smaller political parties, will benefit from a more regulated form of governance, where the personal wealth of political players and their oligarchical connections, are a lesser determinant of electoral success.

At the same time, the strength of commitment to a modern, technocratic management of society and economic growth among all the major parties – the PDI-P, the United Development Party (PPP), Nasdem, PKB and PKS – is still untested.

Unlike the rhetorical polarisations of 2014 and 2019, this new polarisation so farappears to be primarily confined to and visible within the political elite. This elite is defined here as going beyond political parties to include to a significant extent the mainstream media, civil society and its social media. To what extent these differences are being discussed or being perceived as important among Indonesia’s 204 million voters[30] is still unknown. Prabowo was scoring 43-46 per cent for his electability in December 2023 – early January 2024 in polls, but according to survey firm Indikator Politik Indonesia, his numbers possibly stagnated thereafter.[31]

It is worth noting, however, that some polls are recording high numbers for undecided voters. A Kompas poll recorded 28.7 per cent of respondents as being undecided in early December 2023.[32] Another poll on party support for the legislative elections (also on 14 February) noted a 5.9 per cent increase in undecided voters from August 2023, up to 17.3 per cent.[33] There are no polls yet that show what the conscious abstainer or spoiled vote (called golput in Bahasa) might total.[34] The reported stagnating of support for Prabowo in more recent poll results raises questions over what is going on in the minds of voters.

As of 24 January, there are limited signs of the Baswedan and Pranowo campaigns coordinating their efforts, with this scenario being discussed by former vice president Jusuf Kalla, who supports Baswedan.[35] Their immediate aim would be to ensure that Prabowo’s level of support does not exceed the crucial level of 50 per cent, thus ensuring a run-off second round in late June 2024. It is possible that the two coalitions will work together to increase the vote for their individual parties by directing their supporters to vote for each other’s parties in some districts.[36] Baswedan’s running mate, PKB chairperson Muhaimin Iskandar, in his formal greeting at the PDI-P’s 51st anniversary celebration, spoke positively about cooperating with PDI-P, including in a run-off.[37]

The novelty of the current differentiation makes it harder to predict an outcome for the elections. The assumption that Prabowo, with the support of the incumbent Widodo, was assured of a clear win is now being questioned. Has Prabowo’s support stagnated or will some unforeseen element revitalise it? Or has support for him peaked, and will henceforth move downwards?

ENDNOTES

For endnotes, please refer to the original pdf document.

| ISEAS Perspective is published electronically by: ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute 30 Heng Mui Keng Terrace Singapore 119614 Main Tel: (65) 6778 0955 Main Fax: (65) 6778 1735 Get Involved with ISEAS. Please click here: /support/get-involved-with-iseas/ | ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute accepts no responsibility for facts presented and views expressed. Responsibility rests exclusively with the individual author or authors. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form without permission. © Copyright is held by the author or authors of each article. | Editorial Chairman: Choi Shing Kwok Editorial Advisor: Tan Chin Tiong Editorial Committee: Terence Chong, Cassey Lee, Norshahril Saat, and Hoang Thi Ha Managing Editor: Ooi Kee Beng Editors: William Choong, Lee Poh Onn, Lee Sue-Ann, and Ng Kah Meng Comments are welcome and may be sent to the author(s). |

“China as a Rising Norm Entrepreneur: Examining GDI, GSI and GCI” by Manoj Kewalramani

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

• This paper discusses Chinese President Xi Jinping’s flagship global initiatives’ normative implications for the world order.

• It argues that the Global Development Initiative (GDI), Global Security Initiative (GSI) and Global Civilization Initiative (GCI), which are key pillars of China’s proposal to build a community of common destiny for mankind, are driven by Beijing’s desire to cultivate authority in the international system.

• Analysing the speeches by Chinese leaders, policy documents, media and analytical discourse in China, along with policy decisions, this study provides an assessment of the Chinese leadership’s worldview. It places the launch of GDI, GSI and GCI within this context, before detailing the elements of each initiative and offering a critical analysis.

• This study concludes that through GDI, GSI and GCI, the Chinese leadership hopes to shape an external environment that not only ensures regime security but is also favourable to China’s development and security interests. In doing so, however, it is reshaping key norms of global governance towards a fundamentally illiberal direction.

Trends in Southeast Asia 2024/2, January 2024

“TIMOR-LESTE IN ASEAN: Is It Ready to Join?” by Joanne Lin, Sharon Seah, Sithanonxay Suvannaphakdy and Melinda Martinus

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

• After more than a decade of deliberations, ASEAN leaders agreed on 11 November 2022 in principle to admit Timor-Leste as the eleventh member of the regional organization and to grant Timor-Leste observer status to attend all ASEAN meetings. Timor-Leste has demonstrated positive developmental progress, and fact-finding missions across the three ASEAN Community pillars have returned generally optimistic results.

• However, an assessment of Timor-Leste’s ability to fulfil its commitments and obligations reveals that the country will need to close the gap with the ten existing members on matters such as the ratification and implementation of legally binding agreements and derivative work plans. Creating enforcement mechanisms and finding ways to implement commitments at the local level will be important.

• Timor-Leste has put in place institutional structures and implementing agencies for advancing cooperation with ASEAN. It is also moving towards harmonizing its laws with ASEAN instruments. However, its capacity remains in question due to a lack of substantive knowledge and technical expertise among government officials, as well as inadequate infrastructure, logistics and facilities for hosting ASEAN meetings.

• Strengthening human capital will be a top priority for Timor-Leste. This includes not only enhancing its personnel’s knowledge and technical expertise on ASEAN processes and procedures but also skills such as English language proficiency and negotiation. Coordinated capacity-building assistance from ASEAN and dialogue partners will be important. These efforts must also be met with economic diversification and growth of its nascent private sector.

• Apart from bridging gaps, ASEAN needs to grapple with its reservations that Timor-Leste’s economic limitations may slow down the realization of the ASEAN Economic Community. There are also concerns that Timor-Leste’s membership may entrench differences within the bloc, particularly with regard to geopolitical issues, and dilute the organization’s effectiveness or further complicate the consensus-based decision-making process.

Trends in Southeast Asia 2024/1, January 2024

2024/7 “Mohd Na’im Mokhtar: Business as Usual in JAKIM?” by Mohd Faizal Musa

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

- Mohd Na’im Mokhtar was appointed by Anwar Ibrahim to be Minister in the Prime Minister’s Department in charge of Religious Affairs, although he is not an elected politician nor a member of any political party.

- Unknown to many, Na’im had previously served as Chief Judge of the Shariah Court, and was also Director-General of the Shariah Judiciary Department (Jabatan Kehakiman Syariah Malaysia, JKSM) during Pakatan Harapan’s administration from 2018 to 2020.

- According to regulations stipulated by the National Islamic Religious Affairs Council (Majlis Keagamaan Islam, MKI) in 2022, any Prime Minister’s choice for the role of Minister of Religious Affairs requires special consent from the Council of Rulers. This has therefore given rise to some speculation that Na’im’s appointment might not have been due to Anwar’s sole discretion.

- Although credited for various reforms within the Shariah legal system, Na’im also faces criticisms from conservative circles. Furthermore, growing public criticism of the Department of Islamic Development Malaysia (Jabatan Kemajuan Islam Malaysia, JAKIM) makes his leadership of the institution all the more challenging.

- This paper argues that, judging from his track record in handling various episodes, Na’im is likely to navigate a delicate balance between the conservatives and the progressive advocates in the country. With the legacy of revivalist ideals moderated with pragmatism by previous administrations within Malaysia’s multi-racial context, Na’im can be expected to proceed very cautiously on reforms while keeping at bay the extremist voices on both ends of the conservative-liberal spectrum.

* Mohd Faizal Musa is Visiting Fellow at ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute and Research Fellow at Institute of the Malay World and Civilisation (ATMA), National University of Malaysia (UKM).

ISEAS Perspective 2024/7, 29 January 2024

INTRODUCTION

On 2 December 2022, Malaysian Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim unveiled a 28-member Cabinet for his unity government. Of the 28 members, four of them were not Members of Parliament (MP), and had instead been made Senators in order to be appointable as ministers. One of these four was Mohd Na’im Mokhtar, a figure unknown to most; he was chosen by Anwar to be Minister in the Prime Minister’s Department in charge of Religious Affairs.[1] What made his appointment intriguing is that he is the sole Cabinet member who is not with a political party. While he may be unknown to many political enthusiasts, law practitioners—those working in Shariah law—know him very well.

During Pakatan Harapan’s (PH) administration in 2018, Na’im served as Chief Judge of the Shariah Court, as well as Director-General of the Shariah Judiciary Department (Jabatan Kehakiman Syariah Malaysia, JKSM). Given his experience in dealing with Islamic affairs, it was unsurprising that immediately after the announcement of Na’im’s ministerial appointment, Mujahid Yusof Rawa—the individual who previously held Naim’s position during PH’s administration and who was in charge of the Department of Islamic Development Malaysia (Jabatan Kemajuan Islam Malaysia, JAKIM), praised Anwar’s choice.[2]

Na’im is not the first non-political figure to hold the portfolio. The former Federal Territories Mufti, Dr Zulkilfi al-Bakri, held the same portfolio from March 2020 to August 2021 under Muhyiddin Yassin’s administration. However, what makes Na’im’s position unique is that according to the new regulations stipulated by the National Islamic Religious Affairs Council (Majlis Keagamaan Islam, MKI) in 2022, a prime minister’s choice for this particular position requires special consent from the Council of Rulers.[3] JAKIM, which is headed by the minister in question, reports to the MKI which is chaired by the Selangor Ruler, Sultan Sharafuddin Idris Shah.[4] Consequently, the perception arose among political activists that Na’im’s appointment was a privileged decision which was not necessarily made by Anwar himself.

Na’im’s parachuting into the Cabinet therefore calls for an examination of his professional background and its relevance to his portfolio. As the man who has been given a lavish allocation of Malaysia’s 2024 Budget amounting to RM 1.9 billion,[5] it is crucial to analyse how he may perform as minister. While conservative Muslims such as those in Parti Islam SeMalaysia (PAS), right-wing Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs) and even professionals and netizens who are close to the party have claimed he is weak, those in progressive circles are paying careful attention to how he plans to deal with extremist groups and ideas. This paper will look at Naim’s background, his approach to various issues, and perceptions of his performance thus far. In doing so, I will refer to some of the remarks he has made, and also include findings from my engagements with ten Shariah law practitioners from Klang Valley, Negeri Sembilan, and Kelantan. These engagements—which occurred between October and November 2023—reveal observers’ predictions and perceptions of his current and future performance as minister, and whether or not he will undo old religious trends, or even set a new one. Overall, it is believed to be unlikely that Na’im will spark new religious trends or undo old ones, and changes are high that he will maintain the status quo.

GETTING TO KNOW MOHD NA’IM MOKHTAR

Right after being elected as Minister of Religious Affairs, Na’im said that he had an enormous task ahead of him, especially since he did not have a deputy minister to assist him. He was also quick to assure people that he would lead JAKIM as a neutral civil servant, and that any decisions made would be free from political interference.[6] This could be interpreted as his commitment to not entertaining political tantrums in a post-GE15 Malaysia which saw the rise of conservatism and non-violent extremism among segments of the Muslim community. His intended neutrality as a civil servant also implies that he would be answerable to the King (Agong) who is the Head of the Religion, and not necessarily to the government of the day. His neutrality was evident in his handling of various issues including the management of the hajj pilgrimage in 2023, calling out a government agency for not acting quickly enough in taking down dangerous social media content, reprimanding Perikatan Nasional’s (PN) leader Muhyiddin Yassin, and various affairs related to Shariah law, including standardising it as instructed by the Council of Rulers.[7] Na’im also gave strict warnings to the opposition not to use and exploit mosques and prayer halls (surau) to propagate their political agenda.[8]

Born on 25 November 1967, Mohd Na’im Mokhtar graduated with a Bachelor’s degree from the International Islamic University of Malaysia (IIUM), after which he obtained a Masters in Laws from the University of London, and subsequently a PhD in Shariah Law from the National University of Malaysia (Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, UKM). Prior to his entry into the civil service, Na’im started his career as law lecturer at IIUM from 1990 to 1997, after which he practised as a Shariah lawyer in Negeri Sembilan, Melaka and the Federal Territories from 1997 to 1998. Later in 1998, Na’im was elected as a Shariah judge in Petaling Jaya, Selangor, and also sat on the advisory board of several Islamic banks such as CIMB Islamic Bank, Salihin Trustee Bhd, Sun Life Insurance and the American and British Investment Bank Mauritius.[9] On 1 July 2017, Na’im was promoted to be a judge in the Shariah Court of Appeal. Other notable achievements include his receipt of a Chevening Scholarship from the University of Oxford from 2008 to 2009, and a Visiting Fellowship at Harvard Law School from 2012 to 2013.[10] In 2016, Na’im gave a speech on Shariah law in Selangor at an official dinner hosted by the Trial Court of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, United States.[11] This positioned him at the centre of attention and earned him praise from many Shariah practitioners.

BALANCING MINISTERIAL DUTIES AND POLITICAL COMPETITION

As Na’im’s previous appointment was as Director-General of the Shariah Judiciary Department (Jabatan Kehakiman Syariah Malaysia, JKSM) during the time Mujahid was minister, it was soon perceived that Na’im was either friendly towards Parti Amanah Negara (Amanah) and PH, or that his policies would be similar to that of Mujahid’s. Mujahid praised Na’im for a few reasons. First, during Mujahid’s leadership of JAKIM from 2018 to 2020, it was Na’im who played an important role in introducing Gagasan Negara Rahmah (A Vision of a Merciful Country) and Dasar Rahmatan Lil Alamin (Mercy to All Policy). Second, Mujahid observed that Na’im was instrumental in implementing reform within the Shariah legal system by standardising Shariah laws, establishing the Mahkamah Hadhanah (Custody Court), ensuring the strict enforcement of Shariah court decisions regarding alimony for divorcees, and improving the quality of Shariah judges and the Syarie Legal Profession Act (Akta Profesion Guaman Syarie).[12]

Prior to the Cabinet reshuffle on 12 December 2023, there were rumours that Na’im’s position might be affected. Nevertheless, he was quick to master the political game, and given the above-mentioned achievements, he stated that he will continue to carry on his responsibility to the best of his capabilities.[13] Ministers often tend not to make such statements when a Cabinet reshuffle is due, as it is understood that one’s position in the Cabinet is entirely the prime minister’s choice. After the reshuffle, Na’im’s position was safe and he was even given a deputy minister in the form of Dr Zulkifli Hasan, a Malaysian Islamic Youth Movement (Angkatan Belia Islam, ABIM) strongman to assist him. Similar to Na’im, Zulkifli was made a Senator before his ministerial appointment.

However, despite his success in keeping himself in Cabinet, many political activists have claimed that he has failed to stifle PAS’ attacks against the Madani administration, especially during the intense campaign period before the 2023 state elections.[14] Thus, in recent months, Na’im has been trying to gain political credit by actively signalling to Islamic authorities to investigate and quell the allegations surrounding Anwar’s past sodomy charges. Since a recent row in Parliament between Anwar and Bersatu MP Radzi Jidin, PH supporters have taken to the Internet to argue that Anwar has been a victim of qazaf (false accusations), which is considered a crime punishable by Shariah and Hudud law, which is in turn enforced by the relevant state government.[15]

Na’im has also been trying hard to respond to Abdul Hadi Awang’s claims that the government has been helpless in countering the challenges posed by those who are against Islamic law.[16] In responding to these claims and countering the challenges listed below, and to assist JAKIM with the implementation of the vision for Malaysia Madani, Na’im has sought help from four Muslim NGOs namely, Persatuan Wadah Pencerdasan Umat Malaysia (Malaysian Association of Enlightenment Platforms, Wadah), Pertubuhan Ikram (Ikram), ABIM, and Pertubuhan Himpunan Lepasan Institusi Pendidikan Malaysia (Organization of Graduates of Educational Institutions Malaysia, Haluan).[17] However, this move is arguably ambiguous. While Ikram and ABIM are often cited as relatively progressive groups (Hew 2018), Wadah and Haluan tend to be more right-wing. For example, the latter two are intolerant of religious minorities such as the Shi’as.[18] Thus, his working relationship with right-wing groups proves that Na’im is simply continuing what previous administrations always dd. In fact, if one were to focus on his close circle as minister, one might notice that his special officer is Dr Mohd Razak Idris, who was formerly the president of ABIM from 2009 to 2011.[19] This is in addition to the newly elected Deputy Minister Dr Zulkifli Hasan.[20] This strongly indicates that ABIM-like policies on Islamic issues could come to be imposed.

Thus, it is safe to say that interms of administering Islamic affairs, Na’im has been maintaining the status quo. For instance, he has not stopped JAKIM from overstepping boundaries in advising art practitioners about what they can or cannot do. Na’im is behind the banning of a film entitled Mentega Terbang, alleging that it promotes pluralism. He was also critical of the television drama Surat Dari Tuhan which allegedly featured the actors uttering words of vulgarity.[21] To further maintain his authority, Na’im reproached Ipoh Timur’s Democratic Action Party (DAP) MP Howard Lee for quoting Qur’anic verses on his social media platform.[22]

In terms of dealing with LGBT issues, Na’im has maintained the position that JAKIM will not recognise their rights as a community, but that their rights as citizens will not be violated.[23] He also stated that JAKIM will be stern towards Muslims involved in LGBT activities.[24] Even outside of the LGBT community, Muslims are subject to state regulation and scrutiny. For example, JAKIM has been mulling over the idea to send some of its staff to the Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commission to assist in monitoring “deviant postings” on social media. There has also been great scrutiny on Muslims visiting graveyards.[25]

As for non-Muslims, there have been doubts among them with regard to Na’im’s plan to form an out-of-court mediation centre to resolve disputes involving Muslims and non-Muslims, especially in custody cases.[26] In fact, Na’im’s call to harmonise Shariah and civil law has been met with scepticism, especially given his intention to “dignify syariah law to its rightful sovereign position”, thus evoking doubt amongst proponents of the Federal Constitution and Malaysia’s civil laws.[27]

RESPONSES FROM SHARIAH PRACTITIONERS

My interactions with Shariah practitioners show that there are mixed feelings about Na’im. While many have positive sentiments about his legacy and the work that he has done for the legal system, there are those who doubt that he can implement the reforms which they feel are most needed for the country. By reform, these Shariah lawyers refer to the need to ensure that the Shariah court is more powerful than the civil court. In other words, these lawyers would like to see the decisions made by the Shariah court surmount the decisions made by civil judges, especially in cases relating to custody and inheritance.

In terms of politics, most of the Shariah practitioners think Na’im should not bow down to the “liberals”. For example, Yuslan Yusoph, a Shariah lawyer, is critical of Na’im for being too idealistic and believes that the standardisation of Shariah law is not a great achievement. To him, it would be a greater feat to ensure that Shariah law emerges victorious in its potential clashes with civil law. Another lawyer, Mohd Solahuddin, said that Na’im should be “courageous enough to dignify the Islamic agenda and not be too cautious”.[28] While there are those who hope that Na’im will be more aligned with progressive ideas, they are in the minority. For example, Raja Mohamad Haziq expressed his hopes that Na’im will “control religious teachers who have extremist ideas and prevent them from teaching in mosques”.[29] In saying so, he expressed his concerns about the links between PAS and the growing spread of extremist ideas.

The main grievance which many Shariah lawyers share have to do with the challenge brought up by Kelantan-born lawyer Nik Elin Abdul Rashid and her daughter Tengku Yasmin Natasha Tengku Abdul Rahman, who have argued that as many as 20 provisions under the Kelantan Syariah Criminal Code (I) Enactment 2019 are unconstitutional. Some of these provisions address false claims (Section 5), destroying places of worship (Section 11), giving away a Muslim child to a non-Muslim or a morally corrupt Muslim (Section 13), sodomy (Section 14), necrophiliac sexual intercourse (Section 16), bestiality (Section 17), words that break the peace (Section 30), and sexual harassment (Section 31). The Shariah lawyers feel that Na’im has not done enough to address this challenge. Similarly, PAS has also expressed that Na’im is not taking the matter seriously and is putting the primacy of Shariah law at risk. They have also blamed the unity government for not intervening, and have threatened to hold rallies to defend the Shariah, as was done in 2017.[30]