2024/14 “Demographic Transitions in Southeast Asia: Reframing How We Think and Act About Ageing” by Maria Monica Wihardja and Reza Siregar

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

- Population ageing could be a sign of longer lives and healthier old ages, but this demographic factor poses both challenges and opportunities at the same time.

- Managing the ageing transitions will therefore critically shape the existential conditions of each demographic stage.

- This study maps the Southeast Asian economies into various demographic typologies and documents policy recommendations that these economies could adopt, for example, by drawing on the experiences and policy initiatives of other East Asian countries in navigating their ageing population.

* Maria Monica Wihardja is an economist and Visiting Fellow at ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute and Adjunct Assistant Professor at the National University of Singapore; and Reza Siregar is Head of the Indonesia Financial Group (IFG) Progress Indonesia.

ISEAS Perspective 2024/14, 21 February 2024

INTRODUCTION

The Southeast Asian (SEA) region is experiencing intense demographic changes. Unlike their counterparts in Europe and the United States, countries in East and Southeast Asia are ageing at record speed, (World Bank, 2019).[1] While countries in SEA are heterogeneous in their demographic profiles – from the already aged population in Singapore to the still very young population in Cambodia and Lao PDR – none of them is spared from the challenges brought by an ageing population.[2]

Although population ageing could be a sign of longer lives and healthier old ages, demographic transitions can be a ticking time bomb and turn out to be disastrous if countries fail to invest in necessary systems and reforms in time. This paper discusses the challenges faced, and suggests policy recommendations for SEA countries, focusing on the ten ASEAN countries at different stages of demographic transitions, with some comparisons with, and lessons to be learned from, Japan, South Korea and China.

DEMOGRAPHIC TYPOLOGY IN SOUTHEAST ASIA

Scholars have conceptualised three forms of “dividends” from demographic changes (World Bank, 2015). A ‘first demographic dividend’, associated with a growing share for the working-age population, presents opportunities for countries to reap the expanding working age population, which they can do by investing in human capital, creating enough productive jobs and building institutions conducive to savings and transfers. A ‘second demographic dividend’, associated with a declining share for the working-age population, presents the countries with the next group of opportunities to benefit from the more sophisticated workforce; this they can do by moving the workforce into higher productivity sectors and jobs and mobilising savings that the current cohorts of older people had squirrelled away and invested when they were younger. A ‘third demographic dividend’, associated with an already aged or super-aged population, presents further opportunities by ensuring that older people can live with dignity and security, for example, by reframing ageing from being a burden to being a blessing.

Evidence from East Asia during the 1970-2000 period suggests that the contribution on GDP growth from a ‘second demographic dividend’ through a higher productivity growth was 2.2 times larger than the contribution from a ‘first demographic dividend’ through a demographic change (a higher share of working-age population) (World Bank, 2015). Since human capital accumulation is cumulative, failing to reap an earlier demographic dividend could dent the long-term potential of a country. Table 1 summarises various demographic transitions and the channels through which demographic dividends can be reaped. Based on this typology, two countries, Singapore and Thailand, entered the ‘post-dividend’ demographic transition in 2023, associated with the third demographic dividend. Five countries, i.e., Indonesia, Brunei Darussalam, Malaysia, Myanmar, and Vietnam, have entered the ‘late-dividend’ demographic transition, associated with the second demographic dividend. Meanwhile, Lao PDR, the Philippines and Cambodia are still in the ‘early-dividend’ demographic transition, associated with the first demographic dividend.

Table 1: Southeast Asian countries in different stages of demographic transitions

Source: Table 5.1, World Bank, 2015; and authors’ analysis

*Note: This typology is used by the World Bank (2015) and we updated the calculation to year 2023 (see Annex 1).

It is not too late for lower- and upper-middle-income SEA countries to prepare and implement necessary reforms to reap the demographic dividends associated with their stages of demographic transitions, but the progress to reform so far in many of these countries has been slow. Accelerating reforms will be critical for the region and individual countries.

DEMMOGRAPHICS-SENSITIVE POLICIES

What types of policy reforms are needed to address demographic shifts? In the following sections, we will discuss three priority areas that are most salient for SEA countries: (i) facilitating intra– and inter-generational transfers and equity, (ii) maintaining economic growth and labour market dynamism, and (iii) supporting the well-being of the growing older population.

Facilitating intra- and inter-generational transfers and equity

The importance of intra- and inter-generational transfers and equity can perhaps be best analysed by looking at how consumption is financed across one’s lifetime, including through private and public transfers as well as asset-based reallocations (Annex Figure 1). People tend to be net recipients of transfers (consuming more than what is earned from labour income) when they are children and when they are in the post-retirement ages, while people tend to be net donors of transfers when they are in their productive ages (earning more from labour income than what is consumed).

Among the goals of such a life-cycle analysis are to be able to answer the question of how current and future older people (i.e., the young generation today) are being and will be supported, to estimate the potential impact of demographic changes on public finance including the pension and insurance systems, and to ensure inter-generational equity where the younger generation will be supported when they become old to the same extent that they support the older generation today. The pension and insurance systems, capital and financial markets (asset reallocations) and fiscal policies (taxes and social assistance programmes) will define inter- and intra-generational transfers and equity within a country.[3]

As a case in point, public transfers play a big role in supporting the older people in Germany while asset reallocation and private transfers play a more dominant role in the Philippines (Annex Figure 1). While public transfers can protect the more vulnerable older population, asset reallocation and private transfers alone may not, since not all older people, especially poor and vulnerable older people, own assets or have personal savings and/or family to rely on, highlighting the need in the Philippines to improve the social pension, insurance and assistance systems.

Most developing countries in SEA do not yet have mature and well-functioning pension systems (ILO-ASEAN, 2020; Park, 2012). Among ASEAN member states, only 31.5 percent of persons aged 60 years old or older are covered under some form of regular or one-time lump-sum pension payment, compared to 55.2 percent for the Asia Pacific region and 77.3 percent for the East Asian region. Moreover, there are high disparities among ASEAN countries, with more than 80 percent coverage in Thailand and Brunei Darussalam and less than 20 percent coverage in Malaysia, Indonesia, Cambodia and Lao PDR (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Old-age pension beneficiaries in ASEAN member states as percentage (%) of reference population

Source: Table 10, ILO-ASEAN 2020

Note: Data is based on the latest available year.

As a result, they are ill-prepared to provide economic security for the large number of retirees who loom large on the region’s horizon, risking high poverty incidences among their old-age populations in the near future. Social changes such as changing women’s aspirations, including working in nine-to-five formal jobs accompanying the region’s robust growth, have also weakened traditional family-based old-age support, suggesting that formal pension systems will have to play a bigger role in economic security for the growing older population.

There are five policy reforms for developing SEA countries to embrace if they are to establish more mature and well-functioning pension systems (Park, 2012). The first is to strengthen the institutional and administrative capacity of pension systems to enable them to perform their core functions effectively, including collection of contributions. The second is to improve the governance and regulatory framework of pension systems. The third policy reform is to broaden the pension coverage especially since the biggest failure of pension systems is their limited coverage. The fourth is to enhance the financial sustainability of pension systems. This will require bold adjustments in certain parameters, such as retirement ages, contribution rate, coverage rate and benefits. The fifth lesson is the need to generate higher returns for pension assets and deepening domestic financial and capital markets, particularly for long-term maturity assets. Related to the last point on pension assets, Table 2 shows the pension funds’ assets as a percentage of GDP in East and Southeast Asian countries in the period 2001–2021 where data are available.[4] While this rate is as high as 105 percent in total OECD countries and 93.8 percent for Singapore in 2021, it is as low as 8.3 percent in the rapidly ageing Thailand, and 1.9 percent in the soon-to-be-ageing Indonesia.

Table 2: Ratio of pension funds’ assets to GDP (%) in selected countries[5]

Source: OECD Global Pension StatisticsNote: Pension funds’ assets are defined as assets bought with the contributions to a pension plan for the exclusive purpose of financing pension plan benefits.

The case of Indonesia shows that among the challenges to broadening coverage of pension systems are the large informal sector in the economy and the relatively low income per capita of the country (Siregar et al, 2021, Siregar et al, 2022).

The case of Vietnam shows that the financial sustainability of pension systems is crucial to ensuring inter- and intra-generational equity. Currently suffering from two “missing middles”, namely older population who receive neither monthly retirement benefits, national merit benefits nor social pension benefits, and workers in their productive age who are not poor enough to be covered by social assistance but not rich enough to benefit the social insurance system, pose serious challenges to Vietnam’s social protection system. Social assistance (non-contributory cash and in-kind transfers) only covers less than 20 percent of the workforce while social insurance (contributory pensions and health) covers only about 15 percent of the workforce (Hosny and Sollaci, 2022).

Vietnam’s unsustainable pension fund, which is partly due to the large informal sector (estimated at 68.5 percent in 2021), will become a large deficit in about three decades and this may necessitate higher taxes in the future, makes the system unfair both within and across generations (Leung, 2024; Giang, 2012). Besides increasing contribution rates and increasing normal retirement ages to improve the financial balance, in the longer term, the current defined-benefit pension system needs to transit into a more financially sustainable defined-contribution system. A voluntary contributory scheme introduced by the government in 2006 may need better incentives such as tax-funded matching contributions, to attract the more informal workforce into the pension system.

Productivity-led economic growth and labour market dynamism

After a country exits its early-dividend stage and slowly enters into the late- and post-dividend stage, the focus of an economy should be on boosting productivity growth to substitute for the losses in the economically active population. This effort could be complemented with efforts to increase the employment rate and the labour force participation rate, especially among female workers traditionally more disadvantaged than their male workers. Productivity measures such as Incremental Capital Output Ratio (ICOR) and Total Factor Productivity (TFP) can be used to measure labour and firm productivity along with a simple output per labour ratio. However, strengthening human capital by improving early childhood education and health including addressing high chronic malnutrition (stunting) issues should be prioritised.

Table 3 and Table 4 show how over the years (2000-2010 and 2010-2017), a decline in the growth of working-age population aged 15 years old and above (‘demographic change’) in ASEAN countries such as Singapore, Vietnam and Thailand between 2010 and 2017/8 are dragging down growth in per capita value added. This is in contrast to the positive contribution of demographic change to growth in per capita value added in these countries between 2000 and 2010. In Vietnam and Cambodia, declines in the growth of the working-age population were partly compensated by higher productivity growth rates. In Singapore, however, a decline in working-age population was not compensated by a higher productivity growth rate, bringing annual per capita value-added growth rate from 3.4 percent between 2000 and 2010 down to 2.7 percent between 2010 and 2018.

Table 3: Decomposition of Growth in Per Capita Value Added in Japan and Selected SEA Countries, 2000-2010

Source: World Bank’s Jobs Diagnostic Tool, authors’ calculations

Table 4: Decomposition of Growth in Per Capita Value Added in Japan and Selected SEA Countries, 2010-2017

Source: World Bank’s Jobs Diagnostic Tool, authors’ calculations

Demographic differences in the ASEAN+3 region have not only facilitated capital and technological flows but also the flows of labour (Menon, 2009). Although international migration policies could help slow down the rate of ageing, at least in the short run, it is unlikely to structurally reverse the age structure in the long run while managing the consequences of migration policies long after the economy was opened up to international migrants is critical (Magnus, 2015).

Social well-being of the older population

As a country enters its post-dividend phase, one policy focus will be to sustain a decent standard of living for the whole population and maintain the well-being of the older population. There are three specific policy recommendations related to this: flattening the cost of old-age health care and services, harnessing technologies for the older population, and targeting social assistance for vulnerable older population.

(1) Flattening health care costs

As labour force shrinks, soaring old-age health care costs could overstretch the capacity of the government’s budget and aged care system. As an example, South Korea’s health spending as a percentage of GDP was only 3.9 percent in 2000, but increased to 8.1 percent in 2019 (before the COVID-19 pandemic) and 9.7 percent in 2022.[6] Burgeoning health spending easily crowds out other types of spending including other public goods such as education especially in a political setting where citizens over 65 years old form a significant voting bloc such as in the case of Japan (Kuhn, 2023).

The increase in health spending as a percentage of GDP in rapidly ageing Southeast Asia countries is however more muted. Singapore’s GDP share of health expenditure has increased from 3.3 percent in 2000 to 4.4 percent in 2019; Vietnam from 3.8 percent to 5 percent and Thailand from 3.1 percent to 3.9 percent in the same period.

Policies to help flatten old-age health care costs for both the current and future older populations is therefore key. Among policies that could be prioritised include (i) facilitating investment and new research and development to spur innovation for cheaper health services and products, (ii) reforming the often highly concentrated market structure in the pharmaceutical industries, (iii) the use of (AI) technologies and big data including to monitor health and detect illnesses early before they turn chronic as a preventive instead of curative measures, (iv) increase health care resilience by diversifying supply chains (as the COVID-19 has taught us), and (v) buttressing regional cooperation in health and care industries, including, for example, with Japan, which has a dominant share in the production of many advanced medical technologies such as MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging) machines.

It is also well documented that those who remain economically and socially engaged are relatively healthier than those who do not. Positive perceptions of ageing are correlated with a survival advantage, with individuals harbouring such views living approximately eight years longer and exhibiting better memory (Ng, 2024). Conversely, ageism – prejudice against older persons – is identified as a contributor to stress and social isolation, leading to an annual health cost estimate of USD63 billion (Ng, 2024). Therefore, to reduce health care costs, governments could support the older population to remain economically and socially engaged including by creating an age-friendly environment, helping them engage in ‘silver entrepreneurship’ (start-up entrepreneurship by people over the age of 50) and voluntary works while increasing the retirement age and the re-employment age.(7)

(2) Harnessing technologies for an ageing population

Although there have been scepticisms over the use of robots to address a care crisis—including those that arise from the ethical concern of ‘dehumanising care’ (Henwood, 2019) to the disconnection between state-driven vision of robotic care and the intricate everyday realities of care provision (Wright, 2023)—, AI, robots and automated solutions are commonly deployed in the healthcare eco-system and will continue to play a critical role in managing the care crisis in an ageing or aged society.

The wide application of digital technology may, however, leave behind older people who have no or low digital literacy. Ng and Idran (2022 & 2023) and Wright (2023) show how having older adults and care givers as the centre of addressing the care crisis using (digital) technologies is key. For example, Ng and Idran (2022) explore how older adults engaging on TikTok platforms could help reframe the perception on ageing and challenge socially constructed notions of old age by creating TikTok micro-videos that help fight stereotyping and discrimination against older people.

(3) Targeting vulnerable older population with social assistance

In many developing SEA countries, many still earn low incomes and cannot rely on their pension savings, medical insurance and old-age care as old-aged supports. Old-aged social assistance or safety nets are needed. The definition of ‘vulnerability’ itself could vary across countries but with regard to policy design, both the academic and policy communities have reached a consensus that given a limited budget, targeted social assistance is crucial for social policy making in general and for aging policy in particular. Kong and Yang (2018) provide a good example of how a pre-screening tool to identify vulnerable older population is done in the case of China; this is simple enough for policy makers to use and is effective in screening at-risk older population and estimating the appropriate amount of assistance required by the vulnerable older population.

CONCLUSION

In this paper, we focus on three key policy reform areas for SEA namely: (i) ensuring intra– and inter-generational transfers and equity, (ii) maintaining productivity-led economic growth and labour market dynamism, and (iii) supporting the well-being of the older population.

We need also to keep in mind the changing contexts in which countries are ageing today, including the emergence of big data and AI that enable health monitoring in innovative ways, more frequent and intense extreme weather events such as heat waves and natural disasters to which older people are most vulnerable, and changing aspirations of women and older adults with regards to labour force participation (Berd, 2023).

Since Southeast Asian countries are not ageing all at the same time, there is room for regional cooperation. However, of greater concern than protectionist policies on trade flows are the restrictions on cross-border labour mobility, capital and technology. Regional cooperation could ensure more seamless flows to help the region adapt to the inexorable demographic transition towards more aged population. Importantly, we need to reframe how we think and act about ageing, and to see how expenditure on older population can become an investment. Hence, we have to focus our policy making from minimising the costs to maximising the return on investment (Berd, 2023). For developing SEA countries, the time to invest is now.

REFERENCES

Berd, John. 2023. ‘Asia’s Future in the Face of Dramatic Demographic Shifts and their Impact on Healthcare.’ Presentation at the International Forum on the Super Aging Challenge. https://channel.nikkei.co.jp/wass2023e/ifsace231121_03.html

Giang, Thanh Long. 2024. ‘Vietnam’s Aging Population: Challenges and Policy Responses.’ Presentation at the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute webinar, ‘Demographic Transitions in Southeast Asia: Reframing How We Think and Act about Ageing’, January 25. /media/event-highlights/webinar-on-demographic-transitions-in-southeast-asia-reframing-how-we-think-and-act-about-ageing/

Giang, Thanh Long. 2012. ‘Viet Nam: Pension system overview and reform directions.’ Chapter 9 in Park (2012).

Henwood, Melanie. 2023. ‘Why the idea of ‘care robots’ may be bad news for the elderly.’ World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2019/11/care-robots-ai-4ir-elderly-social/?DAG=3&gad_source=1&gclid=Cj0KCQiA4NWrBhD-ARIsAFCKwWtfeolUxCC-DXbEnUOImZUWWFg031WVqsQ7CbC8Nra6xHqUJ6BxuxsaAkMMEALw_wcB

Hosny, Amr, and Alexandre Sollaci. 2022. ‘Digitalization and Social Protection: Macro and Micro Lessons for Vietnam.’ International Monetary Fund Working Paper, WP/22/185. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2022/09/15/Digitalization-and-Social-Protection-Macro-and-Micro-Lessons-for-Vietnam-523399

International Labour Organization (ILO) – Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). 2020. ‘Old-age Income Security in ASEAN Member States – Policy Trends, Challenges and Opportunities’. ASEAN Secretariat Publication. https://asean.org/wp-content/uploads/FINAL_old-age-2021.pdf

Kong, Tao, and Po Yang. 2018. ‘Finding the vulnerable among China’s elderly: identifying measures for effective policy targeting.’ Journal of Aging and Social Policy, Vol. 31, No. 3, pp. 271-290.

Kuhn, Anthony. 2023. ‘The growing concern of Japan’s ‘silver democracy’.’ NPR news. https://www.npr.org/2023/06/28/1184894573/the-growing-concern-of-japans-silver-democracy

Leung, Suiwah. 2024. ‘Solving Vietnam’s social protection sustainability problem.’ East Asia Forum. https://eastasiaforum.org/2024/01/12/solving-vietnams-social-protection-sustainability-problem/

Magnus, George. 2015. The Age of Aging: How Demographics are Changing the Global Economy and Our World. Wiley publication.

Menon, Jayant, and Anna Melendez-Nakamura. 2009. ‘Aging in Asia: Trends, Impacts and Responses.’ Working Paper Series on Regional Economic Integration No.25. https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/28500/wp25-aging-asia.pdf

Ng, Reuben. 2024. ‘Ageism’. Presentation at the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute webinar, ‘Demographic Transitions in Southeast Asia: Reframing How We Think and Act about Ageing’, January 25. /media/event-highlights/webinar-on-demographic-transitions-in-southeast-asia-reframing-how-we-think-and-act-about-ageing/

Ng, Reuben, and Nicole Idran. 2022. ‘Not Too Old for TikTok: How Older Adults Are Reframing Aging.’ The Gerontologist, Vol. 62, Issue 8, pp. 1207-1216. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnac055

Ng, Reuben, and Nicole Idran. 2023. ‘Innovations for an Aging Society through the Lens of Patent Data.’ The Gerontologist. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnad015

Park, Donghyun. 2012. Pension Systems and Old-Age Income Support in East and Southeast Asia. Overview and reform directions. Asian Development Bank & Routledge.

Siregar, Reza, Mohammad Alvin Prabowosunu, and Rizky Rizaldi Ronaldo. 2021. ‘Public Pension Fund Potential in Indonesia.’ IFG Progress Economic Bulletin – Issue 2.

Siregar, Reza, Ibrahim Kholilul Rohman, Mohammad Alvin Prabowosunu, Nurkholis, and Daffa Harafandi. 2022. ‘Income Threshold Estimation Needed to Increase Pension Fund Penetration in Indonesia.’ IFG Progress Economic Bulletin – Issue 19.

World Bank. 2015. ‘Global Monitoring Report 2015/2016: Development Goals in an Era of Demographic Change.’ World Bank Group and International Monetary Fund publication.

World Bank. 2019. ‘Approach Paper. World Bank Support to Aging Countries.’ Independent Evaluation Group. World Bank Group.

Wright, James Adrian. 2023. Robots Won’t Save Japan. Cornell University Press.

ANNEXE

Annex 1: Demographic Typology in Southeast Asia

This typology is used by the World Bank (2015) and we have updated the calculation to year 2023.

Annex Table 1: Criteria of demographic typology

Source: World Bank, 2015 (Table C.2)

Using this typology, we break down countries into two types: those with an increasing share of working-age population and those with a declining share of working-age population (which is usually irreversible). We further break down each of the two types.

We call a country ‘pre-dividend’ if the share of working-age population is increasing and the fertility rate is still above 4, which almost doubles the replacement rate of 2.1.[8] These countries are yet to reap the ‘first demographic dividend’ since the child dependency ratio is yet to decline, a necessary condition that enables countries to harness the first demographic dividend.

We call a country ‘early-dividend’ if the share of working-age population is increasing but the fertility rate has fallen below 4, where the share of young population is expected to rapidly decline. These countries are ripe to reap the ‘first demographic dividend’.

We call a country ‘late-dividend’ if the share of working age population is declining but their fertility rate was still above the replacement rate of 2.1 thirty years ago (a ballpark length from the birth of a parent to a child).[9] These countries are likely to be in the final phase of their ‘first demographic dividend’.

We call a country ‘post-dividend’ if the share of working-age population is declining and the fertility rate has already started to go below the replacement rate of 2.1 in the last three decades. These countries are likely to have passed (or missed) their ‘first demographic dividend’.

Based on this typology, two countries, Singapore and Thailand, have entered ‘post-dividend’ demographic transition. Five countries, i.e., Indonesia, Brunei Darussalam, Malaysia, Myanmar and Vietnam, have entered ‘late-dividend’ demographic transition, while Lao PDR, the Philippines and Cambodia are still in ‘early-dividend’ demographic transition. Compared to eight years ago, some of these countries have transitioned into a different demographic typology, such as Indonesia, Malaysia and Myanmar (from early- to late-dividend) and Thailand (from late-dividend to post-dividend) (Annex Table 2). From Annex Table 2, we can also see how socioeconomic development and ageing go hand in hand.

Annex Table 2: Economies by demographic typology

Source: UN projections, authors’ calculations

Note: Greyed areas mark changes in demographic typology. Countries are ordered based on their income status.

Annex Figure 1: A life-cycle model of private and public financing of lifetime consumption: The Philippines vs. Germany

Source: World Bank (2015), Figure B5.4.1 Note: It is expected that an average person experiences a life-cycle deficit (what is consumed is higher than what is earned) when he or she is still a non-productive child or young adult and when he or she retires from work. When he or she is a non-productive child or young adult, this deficit is commonly financed by his or her parents (through private transfers) and/or the government (through public transfers), e.g., social assistance programmes for poor households with children. This group of population is usually a net recipient of transfers. As he or she starts working, and throughout his or her productive ages, he or she will start earning (labour and non-labour) income and paying taxes while saving part of his or her income (including through pension funds) and/or investing in assets, e.g., buying a house. This group is usually a net donor of transfers. When an individual retires, his or her consumption will again be financed by private and public transfers plus savings and earnings from capital gains. This group is also a net recipient of transfers. Intra- and inter-generational transfers take place from net donors to net recipients.

ENDNOTES

For endnotes, please refer to the original pdf document.

| ISEAS Perspective is published electronically by: ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute 30 Heng Mui Keng Terrace Singapore 119614 Main Tel: (65) 6778 0955 Main Fax: (65) 6778 1735 Get Involved with ISEAS. Please click here: /support/get-involved-with-iseas/ | ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute accepts no responsibility for facts presented and views expressed. Responsibility rests exclusively with the individual author or authors. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form without permission. © Copyright is held by the author or authors of each article. | Editorial Chairman: Choi Shing Kwok Editorial Advisor: Tan Chin Tiong Editorial Committee: Terence Chong, Cassey Lee, Norshahril Saat, and Hoang Thi Ha Managing Editor: Ooi Kee Beng Editors: William Choong, Lee Poh Onn, Lee Sue-Ann, and Ng Kah Meng Comments are welcome and may be sent to the author(s). |

2024/13 “Vietnam and the Russia-Ukraine War: Hanoi’s ‘Bamboo Diplomacy’ Pays Off but Challenges Remain” by Ian Storey

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

- Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Vietnam adopted an essentially neutral position in a thus-far largely successful effort to insulate itself from major power disputes arising from the conflict.

- Vietnam’s response to the Russia-Ukraine War has been conditioned by three factors: the importance of international law; the country’s historical relationship with Russia; and the need to defend its national interests.

- The Kremlin’s attack on Ukraine, and Western responses to it, have exacerbated Hanoi’s concerns about the reliability of Russia as a defence partner.

- To reduce its dependence on Russia, Hanoi has introduced a three-pronged strategy: retrofit existing Soviet/Russian kit; promote the development of a domestic arms industry; and diversify its arms imports.

- The strengthening of the Russia-China strategic nexus affects Vietnam more than any other Southeast Asian country. Hanoi is concerned that Beijing may use its leverage with Moscow to undermine Vietnam’s interests in the South China Sea.

* Ian Storey is Senior Fellow at ISEAS – Yusof Ishak and editor of Contemporary Southeast Asia. He specialises in security issues in Southeast Asia with a particular focus on the South China Sea dispute

ISEAS Perspective 2024/13, 16 February 2024

INTRODUCTION

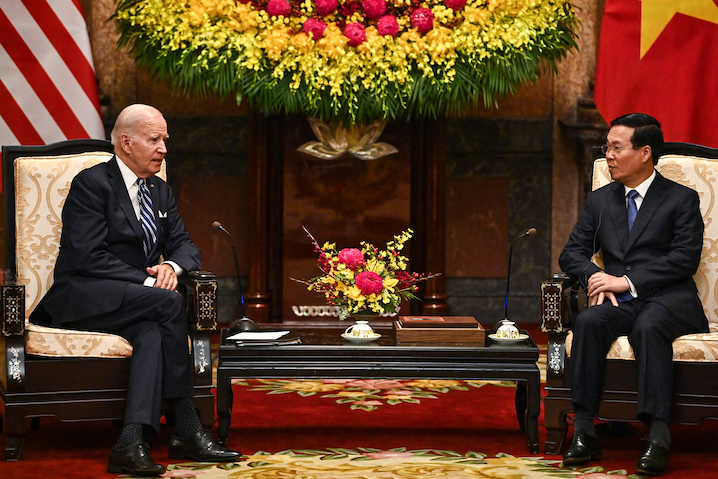

As Vietnam endeavours to navigate an increasingly contested international environment, the country’s leadership has taken pride in its multidirectional ‘bamboo diplomacy’. The idea, promoted by Communist Party of Vietnam (CPV) General-Secretary Nguyen Phu Trong since the mid-2010s, is that by balancing Vietnam’s relations with the major powers – never taking sides, being self-reliant and demonstrating flexibility – it can maintain its agency and interests, while taking advantage of economic opportunities created by major power competition.[1] In late 2023, in a major coup for its bamboo diplomacy, Vietnam hosted visits by both US President Joe Biden and Chinese President Xi Jinping.

Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 was a stress test on Vietnam’s bamboo diplomacy. The Kremlin’s attack on Ukraine elevated tensions between Hanoi’s old partner Russia and its new partners in the West, as well as between the West and Vietnam’s traditional rival, China. In response to the invasion, Vietnam adopted an essentially neutral position so as to insulate itself from major power disputes arising from the war, preserve stable relations with all the main players and stakeholders, and defend its national interests.

While it can be argued that Hanoi’s response to the Russia-Ukraine War has been largely successful in achieving the CPV’s aims, the conflict poses mid-to-long challenges for Vietnam’s Soviet/Russian-centric armed forces and the government’s long-running dispute with Beijing in the South China Sea due to Russia’s growing dependence on its strategic partner, China.

VIETNAM’S RESPONSE TO RUSSIA’S INVASION

For some of Vietnam’s diplomatic elite, the outbreak of the war in Europe can be attributed to the catastrophic failure of the three main players’ foreign policies: the West, for provoking Russia through the eastward expansion of NATO, including the prospect of Ukrainian membership; Russia, for overplaying its hand in the post-Soviet space; and Ukraine, for its failure to address Russia’s legitimate security concerns and properly manage relations with its larger neighbour (which Hanoi considers it has done much more adeptly with China than Ukraine did with Russia).[2]

In the aftermath of the invasion, Hanoi adopted a neutral stance. Vietnam abstained on four of the UNGA resolutions condemning Russia’s attack on Ukraine -on 2 and 24 March 2022, 10 October 2022 and 23 February 2023 -and voted against the motion to remove Russia from the UN Human Rights Council on 7 April 2022. Unlike Singapore, it did not impose unilateral sanctions on Russia.

Vietnam’s response to the outbreak of the conflict was conditioned by three factors: principles, history and interests.

The Kremlin’s invasion was a clear violation of Ukraine’s sovereignty, independence and territorial integrity. Vietnam holds these principles to be sacrosanct because its own sovereignty, territorial integrity and independence have been violated by other countries in the past, including France, Japan, the United States and China. Moreover, Hanoi continues to accuse Beijing of violating its sovereignty in the Paracel and Spratly Islands in the South China Sea.

On 2 March 2022, at the emergency session of the UNGA which had been called to discuss the conflict, Vietnam’s permanent representative, Ambassador Dang Hoang Giang, tried to thread the needle between the importance his country placed on international law and not condemning Russia by name. In his speech before the assembly, Dang stressed how the founders of the UN had enshrined “fundamental principles” in the Charter which had become the “foundation for contemporary international law and friendly relations and cooperation among nations”.[3] Without mentioning Russia directly, he went on to say that “actions not in line with these principles continue to pose serious threats to international peace and security” and “challenge the very relevance and legitimacy of the UN”. Recalling his own country’s history, he argued that wars and conflicts “stem from obsolete doctrines of power politics, the ambition of domination and the imposition and the use of force in settling disputes”. Such disputes, he went on, should only be resolved by “peaceful means, based on the fundamental principles of international law and the UN Charter”. He reiterated the Vietnamese foreign ministry’s line that the “concerned parties” should exercise restraint, cease fighting, resume dialogue and respect international law.

Vietnam’s reluctance to condemn Moscow was due in part to its historical relationship with Russia. Military assistance from the Soviet Union was critical in the CPV’s victory over France and the United States in the First and Second Indochina Wars. During Vietnam’s occupation of Cambodia in the 1980s, the USSR provided Hanoi with vital military, economic and diplomatic support. CPV leaders remain deeply indebted to Moscow, and consistently express their gratitude when meeting their Russian counterparts. As Deputy Prime Minister Tran Hong Ha told his visiting Russian counterpart Dmitry Chernyshenko in April 2023, “Our relations have been through so many challenges, and is filled with loyalty and gratitude [emphasis added]. Vietnam will never forget the support of the Russian people.”[4]

The third and most important factor which determined Vietnam’s response to the invasion was the need to protect the country’s national interests. Russia is not a major source of trade and investment for Vietnam, but it is an old friend and, as described later, an important source of military assistance and a valued partner in the country’s energy sector. As such, since the outbreak of the conflict, Vietnam has endeavoured to preserve cordial ties with Russia, hosting visits by senior Russian officials and even inviting President Vladimir Putin to visit the country.[5]

But more important than keeping on good terms with Russia has been keeping on better terms with the United States, Europe and Japan, Vietnam’s most important trade and investment partners. As such, so far, Hanoi has not undertaken any actions that could be perceived as undermining Western sanctions, including restoring direct flights with Russia after the COVID-19 pandemic (the Russian airline Aeroflot uses both Boeing and Airbus aircraft). Nor did it agree to the Kremlin’s request to re-export Soviet/Russian-made military hardware, munitions and spare parts to replenish the Russian armed forces’ battlefield loses in Ukraine, as Vietnam’s ASEAN partner Myanmar has.[6]

Between the two combatants, keeping Moscow onside was obviously Vietnam’s priority. But in keeping with its bamboo diplomacy, Hanoi has been careful not to offend Kyiv either. After all, Ukraine was once part of the Soviet Union, and therefore played a role in Vietnam’s wars of national liberation. Military equipment manufactured in Ukraine was transferred to North Vietnam; Ukrainian officers in the Soviet Red Army served as advisers to the Vietnam’s People’s Army (VPA); and Vietnamese troops learned to drive tanks at the Malyshev Factory in Kharkiv (scene of some of the heaviest fighting between Russian and Ukrainian forces in the first few months of the war).[7]

This shared history has led Vietnam to refrain from publicly criticising the government of President Volodymyr Zelenskyy for its perceived mishandling of relations with Russia. Moreover, there is clearly some empathy in Vietnam for Ukraine. In the first year of the war, the Vietnamese government provided humanitarian aid to Ukraine by donating US$500,000 to international relief organisations.[8] Vingroup, Vietnam’s largest conglomerate, provided 135 tons of instant noodles to Kharkiv Regional State Administration. Several private educational institutions in Vietnam granted scholarships to Ukrainian students affected by the war.[9] At the G7 summit in Hiroshima in May 2023 – to which Japan invited both Vietnam and Ukraine – Prime Minister Pham Minh Chinh made a point of meeting with President Zelenskyy. The state-run Vietnam News Agency reported that Chinh told Zelenskyy that Vietnam valued its relationship with Ukraine, and that on the issue of the ongoing conflict, Hanoi’s stance was to respect international law and the UN Charter. Tellingly, he added “As a country that has experienced many wars, Vietnam understands the value of peace”.[10]

VIETNAM’S DEFENCE RELATIONS WITH RUSSIA

Since the early days of the Cold War, defence cooperation has been a central pillar of Vietnam-Russia relations. As noted earlier, Soviet (and Chinese) military assistance to the VPA was instrumental in Hanoi’s defeat of French and American forces. Post-Cold War, Vietnam continued to rely on Russia as its primary source of arms. Between 1995 and 2015, Vietnam bought US$5.68 billion worth of Russian arms, or 90 per cent of the country’s defence imports.[11] Most of the VPA’s inventory today-including fighter aircraft, tanks, submarines and surface warships-consists of Soviet and Russia-manufactured kit.

Russia’s occupation of Crimea in 2014 was a turning point in Vietnam-Russia defence relations. Vietnam became concerned that Western sanctions and export controls targeting Russia’s defence industrial sector would affect the quality of Russian weapon systems and disrupt delivery schedules. Those concerns have been greatly exacerbated since the outbreak of the Russia-Ukraine War and the tightening of Western sanctions against Russia. Moreover, the Russian military’s lacklustre performance in Ukraine has unnerved the VPA’s senior leadership.[12] If the Russians failed to defeat a weaker foe, how would the Russia-equipped and trained VPA fare against a much stronger opponent like China’s People’s Liberation Army? This point was underscored most recently when two Russian Navy Taruntul-class missile patrol boats were destroyed by Ukrainian drones in December 2023 and February 2024 respectively.[13] The Vietnamese Navy operates 12 of these vessels.

Since 2014, Vietnam’s need to reduce its military dependency on Russia has been clear. But transitioning away from a major arms supplier is costly and time-consuming. Vietnam will therefore remain dependent on Russia’s defence sector for one or two more decades. To address the problem, Vietnam has implemented a three-pronged strategy: retrofit, indigenise and diversify.

The first prong is to retrofit existing Russian-made equipment to upgrade their capabilities with assistance from other countries that operate Soviet/Russian kit, including India and former Warsaw Pact members such as the Czech Republic.[14]

The second prong is to support the development of an indigenous defence industry so Vietnam can reduce its dependence on other countries for retrofitting support and new acquisitions. Vietnam’s fledgling defence industry, led by state-owned entities such as the telecommunications company Viettel, now produces reconnaissance drones, radars, light arms and missiles.[15] However, Vietnam is still decades away from self-sufficiency in the defence sector.

The third prong is to procure military hardware from countries other than Russia. In fact, Vietnam had already begun a gradual policy of arms diversification before 2014, making purchases from Israel, South Korea, France and Japan. But the Russia-Ukraine War has forced Vietnam to accelerate this policy. Hanoi will likely increase its defence partnership with South Korea and several European countries, including the UK and France. Buying arms from the United States, including fighter aircraft such as second-hand F-16s, remains a possibility, though a number of obstacles stand in the way of a closer US-Vietnamese defence relationship.[16]

Despite the problems facing Russia’s defence industrial sector, a continued role for it in Vietnam’s defence procurement plans cannot be ruled out. The VPA leadership has grown comfortable with its decades-old relationship with Russia and is much less trusting of other countries, especially its former enemy the United States. Moreover, integrating non-Russian equipment with the VPA’s existing inventory will be problematic. In September 2023, it was reported that Vietnam and Russia had agreed to a US$8 billion arms deal using profits from their joint energy venture in Siberia.[17] However, it remains to be seen whether Vietnam follows through with any big-ticket purchases from Russia in the near future.

VIETNAM AND THE RUSSIA-CHINA NEXUS

The Russia-Ukraine War has strengthened the Sino-Russian strategic nexus. Moscow and Beijing share similar worldviews, especially the need to oppose US hegemony. It is not in China’s interests for Russia to lose the war nor see Western sanctions succeed. While Beijing has not explicitly endorsed Russia’s aggression, it has expressed empathy for Moscow’s rationales for launching the invasion, abstained on votes at the UNGA condemning Moscow, increased economic engagement with Russia and provided limited military assistance. However, the war has amplified the power asymmetry in Russia-China relations as Moscow’s political and economic dependence on Beijing has deepened. No other country in Southeast Asia is as affected by this dynamic as Vietnam. It has important implications for Vietnam’s ongoing dispute with China in the South China Sea as well as its defence cooperation with Russia.

Russia has a significant stake in Vietnam’s oil and gas sector. Two state-run Russian energy companies, Zarubezhneft and Gazprom, are currently involved in upstream projects in Vietnam’s 200-nautical mile exclusive economic zone (EEZ). Vietsovpetro (VSP) – a joint venture established by the Soviet Union’s Zarubezhneft and Vietnam’s state-owned PetroVietnam in 1982 – has drilling projects in five offshore oil and gas fields in Vietnam. According to VSP, by the end of 2017, the company had produced 228 million tons of crude oil and 32.5 billion cubic metres of gas, generating revenues of US$77 billion, of which the Vietnamese government received US$48 billion.[18] In 2010, the two companies agreed to extend cooperation until 2030.[19] In 2021, Russia’s largest oil company, Rosneft, sold its interests in two energy fields in the Nom Con Son Basin to Zarubezhneft.[20] Russia’s largest gas company, Gazprom, formed a joint venture with PetroVietnam in 1997, Vietgazprom (VGP), to develop offshore energy projects. These include the Hai Thach and Moc Tinh gas fields which in 2017 accounted for 21 per cent of Vietnam’s overall natural gas production.[21]

Several of the energy blocks in which VSP and VGP operate fall within China’s nine-dash line. Beijing claims jurisdictional rights to maritime resources within that line including oil and gas reserves. In 2016, China rejected a UN-backed arbitral tribunal’s award which ruled the nine-dash line incompatible with the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) and therefore invalid. Russia does not recognise China’s nine-dash line but empathised with its decision to reject the 2016 arbitral tribunal ruling.[22]

Beijing asserts its claims by using vessels from the China Coast Guard (CCG) and the maritime militia to harass survey ships and drilling rigs operating in Southeast Asian states’ EEZs which often overlap with the expansive nine-dash line. Despite tightening relations between Russia and China over the past decade, Beijing has not made an exception for vessels chartered by the Vietnam-Russia joint ventures. Over the past five years, for instance, CCG cutters, often accompanied by Chinese survey ships and fishing boats, have repeatedly intruded into Vietnam’s EEZ, on occasions passing very close to Russian-chartered drilling platforms, resulting in a tense cat-and-mouse game between Vietnamese and Chinese coast guard ships.[23] It was harassment by the CCG which led Rosneft to sell its interests in the Nam Con Son Basin to Zarubezhneft in 2021 in order to protect its commercial interests in China, the company’s largest single customer.[24]

The purpose of China’s intimidation tactics is twofold. First, to create a hostile operating environment for foreign energy companies in the South China Sea, thus forcing them to end their commercial operations (as Repsol from Spain and Marudaba from the United Arab Emirates did in 2020, and Rosneft a year later).[25] Second, to coerce the Southeast Asian claimants into cancelling contracts with foreign energy corporations and enter into new development projects with Chinese corporations.[26]

Neither Vietnam nor Russia is willing to concede to China’s wishes. Indeed, in their 2021 Joint Statement on 2030 Vision for the Development of Viet Nam-Russia Relations, both countries pledged to strengthen cooperation between their oil and gas companies “in accordance with international law, including UNCLOS and Vietnamese and Russian domestic laws’.[27]

Hanoi welcomes the participation of foreign energy companies in its upstream projects not only because they are a source of vital technical expertise and capital, but also because it is Vietnam’s sovereign right under UNCLOS to decide how the hydrocarbon reserves in its EEZ should be developed, and with whom.

Russia too places great importance on the continued operation of its energy companies in Vietnam’s EEZ. The joint ventures with PetroVietnam are highly profitable and generate an important revenue stream at a time when Russian oil and gas exports to Europe have been drastically cut following the imposition of EU sanctions. Moreover, were Russia to acquiesce to China’s demands and end its energy cooperation with Vietnam, it would suffer reputational damage in Vietnam and the rest of Southeast Asia. Regional states would likely conclude that Russia was China’s junior partner and subservient to Beijing’s interests in Southeast Asia. This would undermine Moscow’s claim that it acts as an independent pole in global politics.

Vietnam is concerned that as a result of Russia’s growing dependence on China, Beijing could use its leverage with Moscow to undermine Vietnamese interests. This would include increased pressure on the Kremlin to withdraw its state-owned energy companies from Vietnam’s EEZ and cease arms sales to the VPA, especially offensive weapons that could be used against China in a military confrontation in the South China Sea.

However, Vietnam assesses that in the short term, the strengthening of Russia-China relations may not have a major impact on Vietnamese interests, for two reasons.[28] First, China understands the economic and geopolitical importance of Russia’s operations in Vietnam’s EEZ and is willing to tolerate their continuation for a while longer for the sake of their strategic partnership. Moreover, the power dynamics in Sino-Russian relations are not yet so lopsided that Beijing can force Moscow to do its bidding. Second, China also understands that if it pushes Vietnam too hard, including via its relationship with Russia, it might force Hanoi into a closer relationship with the United States. Nevertheless, a stronger Sino-Russian strategic nexus poses medium to long-term challenges for Vietnam and provides an added incentive for Hanoi to reduce its military dependency on Russia.

ENDNOTES

For endnotes, please refer to the original pdf document.

| ISEAS Perspective is published electronically by: ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute 30 Heng Mui Keng Terrace Singapore 119614 Main Tel: (65) 6778 0955 Main Fax: (65) 6778 1735 Get Involved with ISEAS. Please click here: /support/get-involved-with-iseas/ | ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute accepts no responsibility for facts presented and views expressed. Responsibility rests exclusively with the individual author or authors. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form without permission. © Copyright is held by the author or authors of each article. | Editorial Chairman: Choi Shing Kwok Editorial Advisor: Tan Chin Tiong Editorial Committee: Terence Chong, Cassey Lee, Norshahril Saat, and Hoang Thi Ha Managing Editor: Ooi Kee Beng Editors: William Choong, Lee Poh Onn, Lee Sue-Ann, and Ng Kah Meng Comments are welcome and may be sent to the author(s). |

2024/12 “Being a Member of an Online Group Can Make You More Accepting of Fake News: The Case of Thailand” by Surachanee Sriyai and Akkaranai Kwanyou

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

- In Thailand, various online political communities have emerged since the 2014 coup d’état, as the traditional public sphere became constricted. Since then, every major Thai political party has built an active presence on at least one social media platform.

- Despite their large memberships, little scholarly attention has been given to the role of online groups and how they contribute to the circulation of fake news and disinformation during the campaigning season.

- This paper explores the dynamics of information sharing in online political groups. It tests whether being a member of an online group can make individuals more susceptible to fake news. Preliminary findings from a nationwide survey of 1,225 respondents suggest that membership in an online group can heighten susceptibility to fake news from both the believability and the shareability perspectives.

- However, this survey alone cannot determine why dis/misinformation is more prevalent in online pages and groups. Rather, we can only conclude that there is something about being a member of online political communities that is associated with individuals’ tendency to believe and share fake news.

* Surachanee Sriyai is Visiting fellow at ISEAS Yusof – Ishak Institute, while Akkaranai Kwanyou is PhD candidate at the Computational Social Science Lab, The University of Sydney, and Associate Professor in the Faculty of Sociology and Anthropology at Thammasat University.

ISEAS Perspective 2024/12, 15 February 2024

INTRODUCTION

In Thailand, various online political communities have emerged since the 2014 coup d’état, as the traditional public sphere for freedom of expression became constricted. In the 2020s, more such groups are flourishing and garnering public attention, coinciding with the advent of the youth-led, pro-democracy movement. A remarkable example of such an influential online political group is the Royalist Marketplace founded by political-exile scholar Pavin Chachavalpongpun. This private Facebook group, originally with over 2 million members, has been catching the attention of the public from both sides of the ideological spectrum, through frank and sometimes satirical discussions about the monarchy, a longstanding institution with an exalted position in Thai society. When the first version of the group was geo-locked by the government, Pavin created another, and this gained over 1.1 million members within the course of its first week.5 Presently, the group has 2.3 million members and sees many active discussions on its platform.

Every major Thai political party has now built an active presence on at least one social media platform. For instance, Move Forward Party (MFP), an opposition party, has over a million followers on their Facebook page, while Pheu Thai Party (PTP), a leading part of the governing coalition, has close to 939k followers. Some political candidates have developed their own fanbase and communicate with their supporters via separate online platforms. Pita Limcharoenrat, for instance, has a total of over 2 million followers on all his social media outlets. Rukchanok “Ice” Srinork, an MFP’s parliamentarian, is also known to be communicating with her half-a-million followers about her daily life as an MP via TikTok and Facebook. In addition, many more unofficial online sites have emerged, set up by supporters of parties and candidates, both paid and organic, which have established themselves as influential information channels.

Despite their large memberships, little scholarly attention has been given to these groups and how they contribute to the information ecosystem during campaigns. This paper explores the dynamics of information sharing in online political groups, with the hypothesis that there is a relevant difference in terms of the behaviour of members on one hand, and of non-members on the other, when they receive and process information. We test whether being a member of an online group can make individuals more willing to believe or share fake news. Our preliminary findings suggest that membership of an online group is indeed associated with a tendency to believe and share fake news.

METHODOLOGY AND FINDINGS

Using data from a nationwide survey conducted by Hicken, Sinpeng, and their team about media consumption behaviour during the 2023 Thai general elections,[1] we explore the linkage in Thailand between group membership and fake news. To ensure the representativeness of the study sample relative to the overall population, the researchers conducted a comprehensive field data collection initiative covering all regions of the country, encompassing both urban and rural areas. The total number of participants was 1,225. Furthermore, the sampling strategy aimed through stratification to encompass all age groups in proportion to their representation in the population.

The questionnaire comprises four principal sections and encompasses (1) general information pertaining to the sample group; (2) behaviour in the reception of media and information concerning elections; (3) experiences related to encountering fake news in the media; and (4) political stances and voting behaviours during elections. We derived data from section 2 and 3 that address experiences of encountering fake news in the media by designing the questions to be in a quasi-experimental fashion. During the survey, respondents were exposed to fabricated news posts on Facebook encompassing political and general topics, followed by inquiries such as “How true do you think the content in this post is?” and “How likely would you be to share this content on your own social media?” The former question aims to gauge the perceived believability, while the latter focused on the propensity for shareability. To account for the possibility of a priori exposure to the information, the prompted news posts were completely fabricated by the research team and were never circulated outside the survey.

Based on the individuals’ responses to those questions, we then constructed two scale variables, ranging from 0 to 5, to be used as dependent variables: believability and shareability of fake news. Our decision to separately gauge the effect of believability and shareability aligns with the commonly utilized approach in political communication. As demonstrated in a study conducted by Halpern, Valenzuela, Katz, et al., the phenomenon of receiving fake news is delineated into three primary components: exposure, belief, and sharing of fake news.[2] The mathematical model employed in their investigation elucidated that the measurement of believability and shareability established an intricate relationship referred to as “trust in others”. A believability score of 5 indicates a high level of confidence in the authenticity of fake news, suggesting unquestionable belief in its accuracy. Similarly, for the shareability variable, a score of 5 signifies a strong inclination to share fake news.

Regarding the independent variable, we constructed a dichotomous variable, group membership, based on respondents’ answers to the following question: “Do you belong to a group of supporters of candidates or parties on social media (i.e., LINE group, Facebook group)?” The variable took a value of 1 if the respondent admitted to being a group member; and 0 if otherwise. Then, we ran an Independent Sample T-Test to examine whether there is a statistically significant mean difference in believability and shareability between members and non-members of a political Facebook page and/or Line group. To get a sense of how widespread membership in these groups is among the Thais, we looked at the descriptive statistics concerning the sample’s engagement in online groups. The table below demonstrates the result from our T-Test analysis, showing the difference between the means of the two groups to be statistically significant. In other words, it is supportive of our initial hypothesis that joining an online group has a direct influence on the tendency to both believe and share fake news.

| [Dependent Variables] Response to fake news | [Independent Variables] Membership in a support group for a candidate or political party on social media | N | Mean | S.D. | t-test for Equality of Means | Sig. (2-tailed) |

| a. believability | (1) Yes (2) No | 357 868 | 3.34 3.14 | 1.21 0.98 | 2.84 | 0.005* |

| b. shareability | (1) Yes (2) No | 357 868 | 3.31 2.82 | 1.25 1.19 | 6.29 | 0.000* |

* Significant at level p < 0.01

Furthermore, the box plot shown below also indicates a significant difference in the likelihood of believing and sharing fake news among the two groups of respondents, since the mean value for the believability of fake news was higher for the “YES” group (members) compared to the “NO” group (non-members). The averages were 3.34 and 3.14, respectively. Correspondingly, the average shareability of fake news among the members was also considerably higher than that of the non-members, with average values of 3.31 and 2.82 respectively.

Box plot diagram: The distribution of the believability and shareability of fake news score, classified by group membership

In summary, the data analysis corroborated our hypothesis about information sharing in online groups: There is indeed something significantly different between the behaviour of members and of non-members; it appears that being a member of an online group can make one more susceptible to both believing and sharing fake news. Since the questions that we used to construct the variables in the analysis asked specifically about individuals’ membership to an online group supporting a political party or candidate, we can also infer that the impact of believability and shareability of false information here can potentially affect one’s electoral behaviour too. However, it is also imperative to note that there are at least two key constraints intrinsic to the data used in this analysis. One, the nature of the survey questionnaires only allows us to scratch the surface of the dynamics of information sharing in online groups. A deeper study is needed for a better understanding of the taxonomy of contents that are being shared in these online communities (i.e., what types of content shared). Through this survey alone, we cannot deterministically infer that dis/misinformation are more prevalent in online pages and groups; thus, making their members more susceptible to fake news. Rather, we can only say that there is something about being a member to online political communities which one can associate with an individual’s tendency to believe and share fake news. Two, the survey question did not ask about membership to a Facebook page and a Line group separately, inhibiting us from distinguishing the different nature of the platforms and their varying ability to monitor and moderate contents, albeit that there is anecdotal evidence suggesting that end-to-end encrypted messages can become a hotbed for disinformation propagation and a potential threat to electoral integrity.[3]

CONCLUSION: EXCLUSIVE COMMUNITIES, BIASES, AND TRIBALISM

Our interest in the effect of membership of online groups, especially political ones, is based on the premise that members can gain access to exclusive content that may not be publicly available to non-members. At the very least, subscribing to a political page or account will enable the person to gain “first access” to the content since most platforms’ algorithms tend to prioritize posts from inner circles such as friends, family members, and followed lists. Moreover, becoming a part of such an exclusive community can also serve as a heuristic cue that reinforces the sense of solidarity and belonging among members.

As our findings indicate, being a member of an online group is in fact associated with a stronger tendency to both believe and share fake news. We suggest that this could be due to two reasons: confirmation bias and tribalism. Online platforms tend to function as an “echo chamber” that perpetuates confirmation bias; that is a known global phenomenon. Individuals are likely to believe information that aligns well with their existing beliefs and ideology, thus, reinforcing the perceived credibility and veracity of the information. This concept, however, only partially explains the dynamics of information sharing wherein people share information that they believe in (e.g., high level of believability).

But what leads people to share information that they know is false, especially in the member-only settings? We suggest that tribalism can be one explanation. Once a person joins an online group, subscribing to an exclusive community, they feel that they gain access to things that they would otherwise not have access to; and to some, this even serves as a badge of privilege. This membership thus comes with social costs, and deviating from the constructed norms of the “tribe” may lead to negative consequences. A study of Lawson, Anand and Hakkar in the context of Indian netizens found that group members who do not conform to the behaviours of other group members by sharing the information propagated within the group can be subjected to reduced social interaction over time.[4] So, it is also possible that a group member will share fake news despite having doubts about the veracity, for fear of losing access to future information shared within the group.

Using the concepts of biases and tribalism allows us to move beyond focusing on the direct impact of content on behaviours. In the final analysis, it may not be the regular exposure to false contents per se that contributes to one’s susceptibility to fake news, but rather it is the venue in which they are shared which strengthens that tendency.

REFERENCES

- Clegg, N. How Meta Is Planning for Elections in 2024. Meta https://about.fb.com/news/2023/11/how-meta-is-planning-for-elections-in-2024/ (2023).

- TikTok. TikTok’s Stance on Political Ads. https://www.tiktok.com/creators/creator-portal/en-us/community-guidelines-and-safety/tiktoks-stance-on-political-ads/ (2024).

- O’Carroll, L. & Milmo, D. Musk ditches X’s election integrity team ahead of key votes around world. The Guardian (2023).

- M. Asher, L., Shikhar, A. & Hemant, H. Tribalism and Tribulations: The Social Costs of Not Sharing Fake News. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 152, 611–631 (2023).

- Prachathai. ‘Royalist Marketplace’ geo-blocked in Thailand, unblocked an hour later. Prachathai English (2023).

- Hicken, A. & Sinpeng, A. Thai Political Survey. (2023).

- Halpern, Daniel Valenzuela, S., Katz, J. & Miranda, J. P. From Belief in Conspiracy Theories to Trust in Others: Which Factors Influence Exposure, Believing and Sharing Fake News. In Social Computing and Social Media. Design, Human Behavior and Analytics (ed. Meiselwitz, G.) (Springer, 2019).

- Sriyai, S. The Postings of My Father: Tradeoff Between Privacy and Misinformation. Fulcrum https://fulcrum.sg/the-postings-of-my-father-tradeoff-between-privacy-and-misinformation/ (2023).

ENDNOTES

For endnotes, please refer to the original pdf document.

| ISEAS Perspective is published electronically by: ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute 30 Heng Mui Keng Terrace Singapore 119614 Main Tel: (65) 6778 0955 Main Fax: (65) 6778 1735 Get Involved with ISEAS. Please click here: /support/get-involved-with-iseas/ | ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute accepts no responsibility for facts presented and views expressed. Responsibility rests exclusively with the individual author or authors. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form without permission. © Copyright is held by the author or authors of each article. | Editorial Chairman: Choi Shing Kwok Editorial Advisor: Tan Chin Tiong Editorial Committee: Terence Chong, Cassey Lee, Norshahril Saat, and Hoang Thi Ha Managing Editor: Ooi Kee Beng Editors: William Choong, Lee Poh Onn, Lee Sue-Ann, and Ng Kah Meng Comments are welcome and may be sent to the author(s). |

2024/11 “The Cultural Power of Chinese Herbal Medicine Resulting from the Southeast Asian Belt and Road Corridors” by Khun Eng Kuah

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

- This paper explores the use of Chinese herbal medicine (TCM) as cultural power along the Southeast Asian Belt and Road corridors. It examines both the Mainland Chinese state and the Diaspora Chinese TCM corporations in utilising Chinese herbal medicine to exert influence on each other.

- The Mainland Chinese state expanded TCM into Southeast Asia (SEA) through a series of strategies, including setting up its flagship TCM corporation, the Beijing Tongrentang in SEA countries, establishing joint ventures with SEA Diaspora Chinese TCM corporations and offering joint TCM programmes in educational institutions.

- TCM companies in SEA not only offer herbal products and medication to the local population but also to Mainland Chinese tourists who buy these products in bulk due to the latter’s superior quality.

- TCM as cultural power goes both ways and is tapped upon by different players, not only for instrumental purposes but also to facilitate prospects for collaboration.

* Khun Eng Kuah is a former Visiting Senior Fellow at ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute. She is Distinguished Professor at the School of International Studies/Academy of Overseas Chinese Studies, Jinan University (Guangzhou, China) and Adjunct Professor, Department of Chinese Studies, National University of Singapore. The author is grateful to the Collaborative Center for the Promotion of Chinese Culture in Hong Kong, Macau, Taiwan, and Overseas, Jinan University for partial funding of this project.

ISEAS Perspective 2024/11, 14 February 2024

INTRODUCTION

This paper[1] seeks to demonstrate, using the case of Chinese herbal medicine (TCM), that ‘cultural power’ works multi-dimensionally. While Mainland China may use TCM as soft power to further its socioeconomic interaction with Southeast Asia, the Diaspora Chinese TCM corporations, in turn, extend their presence and influence on Mainland Chinese TCM consumption patterns through the superior quality of their products. This study solely focuses on the two way exchange of TCM products.

In 2013, President Xi Jinping launched the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) as part of China’s economic strategy to expand and widen China’s economic sphere of influence.[2] It specifically targeted six economic corridors that are within its reach of friendly influence. These are (a) New Eurasia Land Bridge Corridor; (b) China-Mongolia-Russia Economic Corridor; (c) China-Central Asia-West Asia Economic Corridor; (d) China-Pakistan Economic Corridor; (e) Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar Economic Corridor; and (f) China-Indochina Peninsula Economic Corridor. The focus of this monumental project is for China to become involved in the port, transportation lines and infrastructure development of these countries. Throughout Central Asia and Central Europe, within the Indian sub-continent to Africa, and in Southeast Asia, a flurry of activities has impacted the macro and micro-economy of those affected by BRI.

Table 1: Export Markets of China’s TCM Products by Regions

| Export Market | Export Quantity (‘000) | Export Amount (‘000 US$) | Export Quantity (%) | Export Amount (%) |

| Asia | 185.4 | 971430.70 | 82.95 | 85.28 |

| Europe | 18.6 | 91020.19 | 8.32 | 7.99 |

| North America | 9.6 | 48970.65 | 4.30 | 4.30 |

| Africa | 7.4 | 13370.16 | 3.31 | 1.17 |

| Asia Pacific | 1.2 | 9320.69 | 0.54 | 0.82 |

| Latin America | 1.3 | 5000.73 | 0.58 | 0.44 |

| Global Total | 223.5 | 1139140.13 | 100 | 100 |

Source: Adapted from 2016 Report on the Developmental Flow of Chinese Herbal Medicine, Department of Market Order, Ministry of Commerce, p.8; and Khun Eng Kuah. 2021. “Traditional Chinese Herbal Medicine as Cultural Power along the Southeast Asian Belt and Road Corridor”. Asian Journal of Social Science 49: 230.

Aside from this, there is also a focus on investments and the types of goods and services that China wishes to import from and export out of these countries. To expand TCM as an important export, the Chinese government targeted countries along the BRI corridors, especially the China-Indochina Peninsular Economic Corridor, commonly known as the BRI Southeast Asian Corridor, where half the ethnic Chinese population residing outside China lives. In December 2016, the State Council formulated the White Paper for China’s Traditional Chinese Medicine; this was followed by the National People’s Congress Standing Committee promulgating the Chinese Medicine Law and the Ministry of Commerce announcing the National Drug Circulation Industry Development Plan (2016−2020).[3] Firstly, it is estimated that the global consumption of TCM will reach USD 50 billion dollars in the years to come,[4] TCM is a lucrative venture for China, which is the biggest producer of such medicinal products and herbs. Asia is the biggest importer of TCM herbs and products and in 2017, it received 85% of the total Mainland Chinese TCM exports. Of the 85%, 54% was exported to ASEAN countries. There was also a 54% increase in export to Southeast Asia, South Asia and the Middle East at the same time, totalling US$760 million.[5]

Secondly, TCM is regarded as an important component of soft power for China to compete as an important humanitarian player in developing nations along the Belt and Road corridors. A report by Xinhua News agency titled “Xinhua Headlines: Traditional Chinese Medicine Gaining Popularity in Africa Amid COVID-19 Outbreak”, revealed that Chinese medical teams have seen a surge in patients seeking TCM treatment and consumption of TCM products to treat Covid-19 infections since early 2020.[6] Another Xinhua News agency reported that “Xinhua Headlines: Traditional Chinese Medicine Aids Global Fights Against COVID-19”. This amply demonstrates that in addition to ‘mask diplomacy’, TCM also became part of the geopolitical contest during the COVID-19 pandemic in countries, especially in Africa and Asia.

Apart from the sale of TCM products, China has also been pushing for the transmission of TCM knowledge through partnerships with various TCM colleges and universities. To name a few, Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman in Malaysia, and Nanyang Technological University and Singapore College of TCM in Singapore, now offer TCM courses at certificate, diploma and degree levels to train local TCM practitioners.[7] In this respect, China has the advantage of producing well-developed TCM training programmes to offer to educational institutions in Southeast Asia and other parts of the world.

Furthermore, Beijing’s flagship TCM corporation Beijing Tongrentang (同仁堂) has been aggressively opening up branches throughout the Asia-Pacific, including 4 branches in the already crowded TCM market in Singapore and 3 branches in Kuala Lumpur, and partnering Hai-O, which has 54 branches for the distribution of its TCM products and herbs.[8] In Indonesia and Thailand, there are standalone Beijing Tongrentang shops selling its products in local TCM shops. In Vietnam, it functions as a joint venture. In Australia, there are 9 integrated Tongrentang stores-clinics in the major cities of Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane, Perth and Cairns.[9] These Tongrentang stores-clinics compete with the local TCM stores for customers and patients. In Singapore and Malaysia, the local ethnic Chinese customers patronize their familiar local TCM stores for TCM products and herbs; likewise, they go to their familiar TCM physicians for treatment purposes. Some of the larger TCM clinics hire mainland Chinese TCM physicians to remedy the shortage of locally-trained TCM physicians.

SOUTHEAST ASIAN KNOWLEDGE OF TCM AND CULTURAL POWER

Southeast Asia houses around 30 million of the 60 million global Diaspora Chinese, and many of them regard TCM as an important alternative treatment for health and illness. There are many TCM halls that sell traditional Chinese herbs and herbal drinks, in addition to the numerous TCM clinics. This attests to the continued importance of TCM within the Diaspora Chinese universe. In fact, 85.5% of China’s TCM products are exported to Asia, including Southeast Asia. In 2017, the export share of TCM and herbal products to ASEAN countries was around 34%.[10]

Traditionally, TCM products have been consumed regularly in Southeast Asia, and countries such as Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia, the Philippines and Thailand have many local established TCM institutions that offer TCM training programmes. Their TCM corporations and factories produce and package TCM products and treatments according to the needs of the local communities. At the same time, they have expanded into the global market.

Especially in Singapore and Malaysia, there are several big local companies such as Eu Yan Sang and Hai-O Group which specialise in traditional Chinese medicine, Chinese herbs, as well as herb-based health supplements. Eu Yan Sang also produces globally sought-after Chinese herb-based health supplements and medicated oil. They also specifically produce a range of women-oriented products catering to menstruation, pregnancy and post-natal treatment.[11] In recent years, Eu Yan Sang expanded globally and into Mainland China, but there has been less success in the latter case, given the stringent Mainland Chinese laws with regards to pharmaceutical products. Nevertheless, the company is scaling up its presence in China.[12] Other TCM companies expanding in the Singapore market include ZTP, established in 1997 and now has at least 40 retail outlets,[13] and Wong Yiu Nam Medical Hall, an old brand TCM company that was first established in 1935 in Singapore. Wong Yiu Nam was acquired in 2009 by the Taiwanese healthcare group, Ma Kuang Healthcare Group. It continues to provide TCM products and herbs to the local population and also tourists as well as patients of the Ma Kuang TCM clinics in Singapore. Ma Kuang TCM clinics are also found in China and Taiwan.[14]