EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

- In the past decade, Vietnam and the United States have incrementally strengthened security cooperation across various areas, including maritime security, defence sales, search and rescue, humanitarian and disaster relief, war legacy issues, and peacekeeping.

- Hanoi and Washington have pledged to enhance and broaden their security relations under the recently established comprehensive strategic partnership (CSP).

- Several conducive factors support the advancement of Vietnam-U.S. security cooperation in the upcoming years. These include growing strategic convergence, a deepening network of shared defence partners, and Vietnam’s military modernization efforts.

- However, sudden leaps or dramatic breakthroughs in Vietnam-U.S. security cooperation are unlikely due to certain constraints. These include Vietnam’s cautious approach, defence cooperation not being the top priority under the CSP, defence interoperability gaps, and lingering trust deficits.

- Therefore, despite the recent upgrade in diplomatic status, Vietnam-U.S. security cooperation has not reached a new level. Nonetheless, expanded defence collaboration in soft areas could help overcome some of the existing constraints and advance mutual strategic interests.

* Phan Xuan Dung is Research Officer in the Vietnam Studies Programme of the ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute. Hoai Vu is Research Assistant at the Institute for Foreign Policy and Strategic Studies under the Diplomatic Academy of Vietnam.

ISEAS Perspective 2024/10, 6 February 2024

INTRODUCTION

Since establishing a ‘comprehensive partnership’ in 2013, Vietnam and the United States have incrementally expanded their security relations, a domain that was hitherto sensitive and limited in scope. In 2015, the two countries adopted the Vietnam-U.S. Joint Vision Statement on Defence Cooperation, which codified activities already undertaken under the 2011 Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) on Advancing Bilateral Defence Cooperation.[1] Vietnam and the U.S. also engage in two dialogue mechanisms — the Political, Security, and Defence Dialogue and the Defence Policy Dialogue. Guided by these bilateral frameworks, Vietnam-U.S. security cooperation has progressed significantly across various areas, including maritime security, defence sales, search and rescue (SAR), humanitarian assistance and disaster relief (HADR), war legacy issues and peacekeeping.

Despite these remarkable strides, Vietnam-U.S. security cooperation remains at a low level, and primarily involves soft forms of engagement.[2] The recent upgrade of bilateral ties to a comprehensive strategic partnership (CSP) raises the question of whether this will change.

This article examines the recent progress in Vietnam-U.S. security cooperation and discusses its prospects under the CSP. It argues that given the current facilitators and constraints, the two countries will continue to advance defence collaboration at a measured pace, focusing on areas of low sensitivity.

RECENT PROGRESS IN VIETNAM-U.S. SECURITY COOPERATION

Maritime Security and Defence Articles

Maritime security and defence articles are key components in Vietnam-U.S. growing defence links. From 2017 to 2023, the U.S. State Department granted Vietnam approximately US$104 million in security assistance through the Foreign Military Financing (FMF) programme, aiming to bolster Vietnam’s maritime security and law enforcement capabilities.[3] Additionally, Vietnam received a separate US$81.5 million from FMF in 2018 as part of the U.S. Indo-Pacific Strategy.

A notable aspect of bilateral maritime security cooperation is U.S. port calls to Vietnam and joint naval exercises. After Vietnam opened the Cam Ranh Bay Military Port to all foreign naval vessels in 2010, the USNS Richard Byrd transport ship became the first to use the port’s logistical services in 2011.[4] Since then, U.S. ships have docked at the port for logistics and maintenance services almost every year. Three U.S. aircraft carriers — USS Carl Vison, USS Theodore Roosevelt, and USS Ronald Reagan — made port calls and held exchange activities in Vietnam in 2018, 2020 and 2023, respectively. Several U.S. naval vessels have visited Vietnamese ports and conducted non-combatant drills known as Naval Engagement Activity (NEA), with the Vietnam People’s Navy. The latest iteration of NEA, conducted in 2017, focused on diving, search and rescue operations, and undersea medicine.[5] Moreover, since 2016, Vietnam has participated in U.S.-led multilateral maritime exercises, including the Southeast Asian Maritime Law Enforcement Initiative (SEAMLE), the ASEAN-U.S. Maritime Exercise, and the Rim of the Pacific Exercise (RIMPAC).[6]

The U.S. fully lifted its lethal arms embargo on Vietnam in 2016, enabling Vietnam to procure U.S. equipment to modernize its military. From 2016 to 2021, the U.S. authorized the permanent export of more than US$29.8 million in defence articles to Vietnam.[7] The U.S. Defence Department’s active Foreign Military Sales with Vietnam has also surpassed US$118 million. Key U.S. arms transfer to Vietnam includes the handover of two decommissioned Hamilton-class cutters, currently the largest cutters in the Vietnam Coast Guard (VCG). In 2023, the U.S. promised the delivery of the third one,[8] making Vietnam and the Philippines the only countries to receive three U.S. Hamilton-class cutters (other recipients have received either one or two).[9] The U.S. has also supplied the VCG with six Boeing Insitu ScanEagle tactical drones and 24 Metal Shark patrol boats.[10] Additionally, Vietnam has bought 12 Beechcraft T-6 Texan II trainer planes as part of a package that comes with logistical and technical support.[11]

SAR and HADR

Given Vietnam’s vulnerability to natural disasters and climate change impacts, enhancing disaster preparedness and recovery capabilities is crucial. Thus, cooperation with the U.S. in SAR and HADR activities plays a vital role in augmenting Vietnam’s security. In 2014, the USS John S. McCain conducted a SAR exercise with the VPN off the coast of Da Nang as part of its NEA with Vietnam.[12] This marked the first SAR training activity between the two navies. Subsequent NEAs also included exercises on SAR and HADR. In 2016, the two countries signed a letter of intent to form a working group to explore the possibility of storing supplies in Vietnam for HADR purposes.[13] Vietnam has also participated in multilateral cooperation projects on HADR and joint HADR exercises under the Pacific Partnership and Pacific Angel engagements.

War Legacy Issues

Collaboration to address the consequences of the Vietnam War, including unexploded ordnance (UXO), Agent Orange, and soldiers missing in action (MIA), continues to serve as the foundation of Vietnam-U.S. defence relations. The U.S. has provided over US$230 million for UXO mitigation efforts in Vietnam.[14] In 2018, the two governments celebrated the completion of the six-year joint dioxin remediation project in Da Nang. A year later, joint cleanup efforts commenced at Bien Hoa Air Base, the largest remaining dioxin hotspot in Vietnam. The U.S. government’s financial contribution for this project currently stands at US$218 million, including US$90 million from the U.S. Defense Department.[15] In addition, as of 2023, the U.S. has provided US$139 million to fund health programmes that support Vietnamese with disabilities linked to Agent Orange exposure.[16] Regarding the search for American MIAs, as of June 2023, 151 unilateral and joint remains evacuation missions have been conducted, leading to the repatriation of the remains of 734 American soldiers.[17] In 2021, Washington officially began assisting Hanoi in identifying the remains of Vietnamese MIAs through a programme funded by the U.S. Defense Department.[18] Since then, the U.S. has provided Vietnam with more than 30 sets of documents related to Vietnamese MIAs, along with many war artifacts.[19]

Peacekeeping

In recent years, Vietnam has actively participated in United Nations peacekeeping missions, with support from several partners, including the U.S. In 2015, the two countries signed an MOU on peacekeeping, cementing their cooperation in experience sharing, personnel training, technical assistance, equipment, and infrastructure support.[20] Such cooperation lays the groundwork for future bilateral cooperation on peacekeeping missions. Under the Global Peace Operations Initiative (GPOI), the U.S. has spent US$10.87 million to support Vietnam’s peacekeeping contributions, including the deployment of a level-2 field hospital to the UN Mission to South Sudan in 2018.[21]

VIETNAM-US SECURITY COOPERATION UNDER THE CSP: FACILITATORS AND CONSTRAINTS

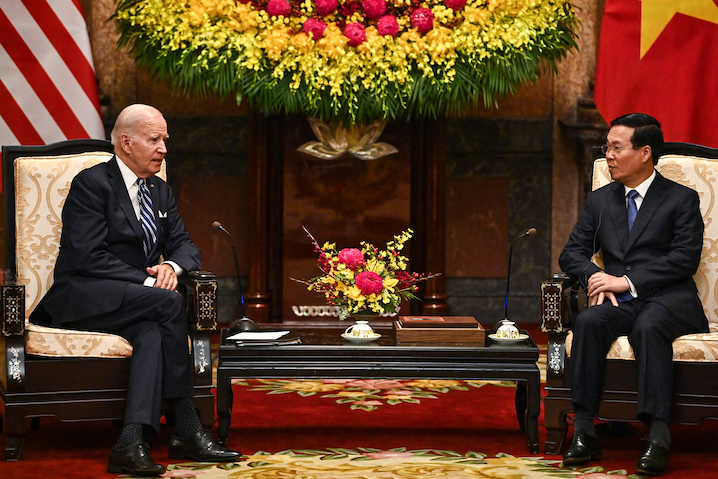

Over the past decade, Vietnam-U.S. security cooperation has witnessed substantial growth under the comprehensive partnership. This positive trajectory is expected to continue under the CSP established during President Joe Biden’s visit to Hanoi in September 2023. The joint leaders’ statement on the Vietnam-U.S. CSP reaffirms continued cooperation on maritime security, SAR, HADR, war legacy issues, and peacekeeping operations.[22] On defence industry and trade cooperation, the statement underscores the U.S. commitment to assist Vietnam in developing self-reliant defence capabilities. A new development is the establishment of a Law Enforcement and Security Dialogue between relevant law enforcement, security, and intelligence agencies.[23]

This section discusses the facilitators and constraints that will shape Vietnam-U.S. security cooperation under the CSP in the upcoming years.

Facilitators

First, the two countries share growing strategic convergence, aligning on key bilateral and regional security issues. As stated in the joint statement on the CSP, the U.S. supports a strong, independent, self-reliant, and prosperous Vietnam in safeguarding its sovereignty and territorial integrity.[24] Regionally, the U.S. envisions a unified and robust ASEAN where Vietnam plays an active role in promoting the group’s centrality in addressing regional security issues. The joint statement also reiterates the two countries’ mutual interests in promoting freedom of navigation and upholding international law in the South China Sea. Moreover, the importance of Vietnam’s geostrategic position in the U.S. Indo-Pacific strategy has been increasingly stressed by U.S. officials and U.S. national security documents.[25] This underscores Washington’s commitment to work with Hanoi in promoting a shared vision of regional security.

Second, Vietnam-U.S. security cooperation stands to benefit from a deepening network of shared defence partners. Vietnam has been strengthening bilateral ties with key U.S. allies and partners in Asia, many of which are its comprehensive strategic partners (India, Japan, South Korea) or soon-to-be comprehensive strategic partners (Australia,[26] Indonesia,[27] Singapore,[28] and Thailand[29]). In 2022, ASEAN also upgraded its relations with the U.S. to a CSP, paving the way for new maritime and defence initiatives.[30] These developments position Vietnam and the U.S. to expand the scope of their defence cooperation, particularly on maritime security and peacekeeping, under trilateral, quadrilateral, and multilateral frameworks.[31]

Third, Vietnam’s military modernization efforts present opportunities for further collaboration on defence articles and technology. After the 13th Party Congress in 2021, Vietnam approved a plan to build a streamlined and strong army by 2025 and a revolutionary, regular, elite, and modern army by 2030.[32] Vietnam has also strived to diversify its arms imports and boost domestic defence production capabilities to become more self-sufficient. The U.S. is recognized as a key partner in these efforts. This was made evident in the presence of several major American defence firms at Vietnam’s first international defence expo in December 2022. U.S. Ambassador to Vietnam, Marc Knapper, said that the event “represents a new stage in Vietnam’s efforts to globalize, diversify, and modernize, and the United States wants to be part of it.”[33] Indeed, following the expo, Lockheed Martin, Boeing, Raytheon, and Textron reportedly held discussions with top Vietnamese government officials regarding the possible sales of helicopters and drones to Vietnam.[34]

Constraints

Despite these conducive factors, sudden leaps or dramatic breakthroughs in Vietnam-U.S. security cooperation are unlikely due to several constraints.

The first is Vietnam’s cautious approach to deepening ties with the U.S. in order to avoid negative reactions from China. Despite concerns over China’s maritime ambitions, Hanoi prioritises maintaining a stable and peaceful relationship with its northern neighbour. China might feel threatened by bolstered Vietnam-U.S. defence ties and respond with punitive actions against Vietnam. Thus, Hanoi has made efforts to reassure Beijing that its CSP with Washington is not an anti-China security pact. During recent Vietnam-China high-level meetings that occurred around the upgrade, Vietnamese leaders repeatedly reaffirmed positive bilateral ties with China and Vietnam’s ‘four nos’ defence policy.[35] Notably, Vietnam hosted President Xi Jinping in December 2023, just three months after Biden’s visit. On this occasion, Vietnam elevated ties with China by establishing a “community of a shared future”,[36] seemingly to balance the upgrade with the U.S.

Given its sensitivities to rising tension between the two great powers, Vietnam might scale back on joint naval activities and military training with the U.S. to keep a low profile. This could explain why Vietnam cancelled 15 defence engagement activities with the U.S. in 2019[37] and did not participate in RIMPAC in 2022, despite having participated in 2018.[38] Vietnam will also be hesitant to engage in combat military exercises with the U.S. in the South China Sea.

A second related constraint is that defence cooperation is not the top priority under the CSP. In the joint statement on CSP, economic and technological cooperation are clearly the main focus, while defence and security ties receive less attention. Moreover, the statement leans towards non-traditional security issues that the two countries have already been collaborating on.

This makes sense as Vietnam’s primary motivation for seeking a CSP with the U.S. was not defence needs. The upgrade aligned with Vietnam’s desire to create a robust and diverse network of strategic partners to ensure three key long-term objectives — security, prosperity, and international status. While the U.S. is seen as an important partner in all three aspects, Vietnam currently emphasizes economic development goals.[39] Hence, for Vietnam, the CSP is more about economics than defence and security.[40]

Washington initially expected that a strategic partnership with Hanoi would result in stronger bilateral defence ties to counter Beijing’s maritime ambitions. However, leading up to the establishment of the CSP, the U.S. had progressively understood that Vietnam would not be comfortable with making the CSP all about defence and security. In various official and unofficial exchanges, U.S. officials and scholars recognized Vietnam’s delicate approach, as well as the need for more patience on the U.S. side.[41]

The third constraint are the defence interoperability gaps between Vietnamese and American forces. A major obstacle is the language barrier. Proficiency in English is still a challenge for the Vietnamese military, and few American personnel can speak Vietnamese.[42] Another obstacle is the low level of cooperation on defence sales, exemplified by Vietnam’s limited import of U.S. weapons. Some scholars have suggested that Vietnam could elevate bilateral defence ties with the U.S. by concluding large-scale arms deals.[43] However, since the lifting of the U.S. arms embargo in 2016, no such deal has transpired. The U.S. is reportedly in talks with Vietnam on the possible sale of F-16 fighter jets.[44] Vietnam has yet to confirm this information, and the deal might not materialize. In the past, Vietnam has shown reluctance to buy major U.S. weapons, such as a second-hand F-16 fighter jet and a P-3C Orion maritime patrol aircraft.[45] Hanoi worried that purchasing major offensive weapons from the U.S. could irk Beijing, especially after the high-profile CSP upgrade. Moreover, there are interoperability concerns over Vietnam’s limited capacity to acquire and integrate U.S. military technology. These include high costs, a steep learning curve, and incompatibility with Russian-made equipment, which currently forms the majority of Vietnam’s weapon systems.[46]

Last but not least, trust deficits between the two countries remain. Despite the increased U.S. recognition of Vietnam’s one-party state system, political differences could still impede defence cooperation. In particular, Hanoi fears that the U.S. Congress might reject equipment sales due to concerns over human rights conditions in Vietnam.[47] Divergent stances on the Russian-Ukraine war, along with Vietnam’s continued reliance on Russia for major arms supplies, also hinder greater strategic trust. Vietnam is cognizant of potential sanctions under the U.S. Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act for buying Russian weapons.[48] Finally, Hanoi has reasons to doubt Washington’s commitments to the region in the upcoming years, given the U.S. ongoing preoccupation with conflicts in Europe and the Middle East.

CONCLUSION

Despite the recent upgrade in diplomatic status, Vietnam-U.S. security cooperation has not reached a new level. Instead, bilateral military relations will continue to concentrate on areas of low sensitivity, including maritime law enforcement, SAR, HADR, war legacy issues, and peacekeeping. Nonetheless, expanding collaboration in these fields could mitigate some of the existing constraints in Vietnam-U.S. defence ties and advance mutual strategic interests.

The US should provide more funding and equipment for Vietnam to enhance its self-reliant defence capabilities, as stated in the CSP. However, it is imperative that the U.S. consider Vietnam’s post-upgrade sensitivities and refrain from pushing for large-scale arms trade that could alarm China. The priority should be to help Vietnam modernize the VCG and improve its maritime domain awareness through equipment transfers and technical assistance. This serves the mutual interests of both countries by promoting freedom of navigation and upholding international law in the South China Sea.

In addition, boosting education and training for Vietnamese military officers will help bridge interoperability gaps between US and Vietnamese military forces. This could include more opportunities for Vietnamese officers to join English language training programmes and study in U.S. institutions. The U.S. should also invite Vietnam to join more non-combat bilateral and multilateral naval exercises. This will foster professional and operational relations between the two countries and with other defence partners.

Finally, increased U.S. efforts to address Agent Orange and UXO, as well as assisting Vietnam in the search for its MIAs, can play an important role in reducing trust deficits. Vietnamese leaders have consistently indicated that greater U.S. efforts to address war consequences are a prerequisite for bilateral cooperation in other areas.[49]

ENDNOTES

For endnotes, please refer to the original pdf document.

| ISEAS Perspective is published electronically by: ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute 30 Heng Mui Keng Terrace Singapore 119614 Main Tel: (65) 6778 0955 Main Fax: (65) 6778 1735 Get Involved with ISEAS. Please click here: /support/get-involved-with-iseas/ | ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute accepts no responsibility for facts presented and views expressed. Responsibility rests exclusively with the individual author or authors. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form without permission. © Copyright is held by the author or authors of each article. | Editorial Chairman: Choi Shing Kwok Editorial Advisor: Tan Chin Tiong Editorial Committee: Terence Chong, Cassey Lee, Norshahril Saat, and Hoang Thi Ha Managing Editor: Ooi Kee Beng Editors: William Choong, Lee Poh Onn, Lee Sue-Ann, and Ng Kah Meng Comments are welcome and may be sent to the author(s). |