2024/12 “Being a Member of an Online Group Can Make You More Accepting of Fake News: The Case of Thailand” by Surachanee Sriyai and Akkaranai Kwanyou

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

- In Thailand, various online political communities have emerged since the 2014 coup d’état, as the traditional public sphere became constricted. Since then, every major Thai political party has built an active presence on at least one social media platform.

- Despite their large memberships, little scholarly attention has been given to the role of online groups and how they contribute to the circulation of fake news and disinformation during the campaigning season.

- This paper explores the dynamics of information sharing in online political groups. It tests whether being a member of an online group can make individuals more susceptible to fake news. Preliminary findings from a nationwide survey of 1,225 respondents suggest that membership in an online group can heighten susceptibility to fake news from both the believability and the shareability perspectives.

- However, this survey alone cannot determine why dis/misinformation is more prevalent in online pages and groups. Rather, we can only conclude that there is something about being a member of online political communities that is associated with individuals’ tendency to believe and share fake news.

* Surachanee Sriyai is Visiting fellow at ISEAS Yusof – Ishak Institute, while Akkaranai Kwanyou is PhD candidate at the Computational Social Science Lab, The University of Sydney, and Associate Professor in the Faculty of Sociology and Anthropology at Thammasat University.

ISEAS Perspective 2024/12, 15 February 2024

INTRODUCTION

In Thailand, various online political communities have emerged since the 2014 coup d’état, as the traditional public sphere for freedom of expression became constricted. In the 2020s, more such groups are flourishing and garnering public attention, coinciding with the advent of the youth-led, pro-democracy movement. A remarkable example of such an influential online political group is the Royalist Marketplace founded by political-exile scholar Pavin Chachavalpongpun. This private Facebook group, originally with over 2 million members, has been catching the attention of the public from both sides of the ideological spectrum, through frank and sometimes satirical discussions about the monarchy, a longstanding institution with an exalted position in Thai society. When the first version of the group was geo-locked by the government, Pavin created another, and this gained over 1.1 million members within the course of its first week.5 Presently, the group has 2.3 million members and sees many active discussions on its platform.

Every major Thai political party has now built an active presence on at least one social media platform. For instance, Move Forward Party (MFP), an opposition party, has over a million followers on their Facebook page, while Pheu Thai Party (PTP), a leading part of the governing coalition, has close to 939k followers. Some political candidates have developed their own fanbase and communicate with their supporters via separate online platforms. Pita Limcharoenrat, for instance, has a total of over 2 million followers on all his social media outlets. Rukchanok “Ice” Srinork, an MFP’s parliamentarian, is also known to be communicating with her half-a-million followers about her daily life as an MP via TikTok and Facebook. In addition, many more unofficial online sites have emerged, set up by supporters of parties and candidates, both paid and organic, which have established themselves as influential information channels.

Despite their large memberships, little scholarly attention has been given to these groups and how they contribute to the information ecosystem during campaigns. This paper explores the dynamics of information sharing in online political groups, with the hypothesis that there is a relevant difference in terms of the behaviour of members on one hand, and of non-members on the other, when they receive and process information. We test whether being a member of an online group can make individuals more willing to believe or share fake news. Our preliminary findings suggest that membership of an online group is indeed associated with a tendency to believe and share fake news.

METHODOLOGY AND FINDINGS

Using data from a nationwide survey conducted by Hicken, Sinpeng, and their team about media consumption behaviour during the 2023 Thai general elections,[1] we explore the linkage in Thailand between group membership and fake news. To ensure the representativeness of the study sample relative to the overall population, the researchers conducted a comprehensive field data collection initiative covering all regions of the country, encompassing both urban and rural areas. The total number of participants was 1,225. Furthermore, the sampling strategy aimed through stratification to encompass all age groups in proportion to their representation in the population.

The questionnaire comprises four principal sections and encompasses (1) general information pertaining to the sample group; (2) behaviour in the reception of media and information concerning elections; (3) experiences related to encountering fake news in the media; and (4) political stances and voting behaviours during elections. We derived data from section 2 and 3 that address experiences of encountering fake news in the media by designing the questions to be in a quasi-experimental fashion. During the survey, respondents were exposed to fabricated news posts on Facebook encompassing political and general topics, followed by inquiries such as “How true do you think the content in this post is?” and “How likely would you be to share this content on your own social media?” The former question aims to gauge the perceived believability, while the latter focused on the propensity for shareability. To account for the possibility of a priori exposure to the information, the prompted news posts were completely fabricated by the research team and were never circulated outside the survey.

Based on the individuals’ responses to those questions, we then constructed two scale variables, ranging from 0 to 5, to be used as dependent variables: believability and shareability of fake news. Our decision to separately gauge the effect of believability and shareability aligns with the commonly utilized approach in political communication. As demonstrated in a study conducted by Halpern, Valenzuela, Katz, et al., the phenomenon of receiving fake news is delineated into three primary components: exposure, belief, and sharing of fake news.[2] The mathematical model employed in their investigation elucidated that the measurement of believability and shareability established an intricate relationship referred to as “trust in others”. A believability score of 5 indicates a high level of confidence in the authenticity of fake news, suggesting unquestionable belief in its accuracy. Similarly, for the shareability variable, a score of 5 signifies a strong inclination to share fake news.

Regarding the independent variable, we constructed a dichotomous variable, group membership, based on respondents’ answers to the following question: “Do you belong to a group of supporters of candidates or parties on social media (i.e., LINE group, Facebook group)?” The variable took a value of 1 if the respondent admitted to being a group member; and 0 if otherwise. Then, we ran an Independent Sample T-Test to examine whether there is a statistically significant mean difference in believability and shareability between members and non-members of a political Facebook page and/or Line group. To get a sense of how widespread membership in these groups is among the Thais, we looked at the descriptive statistics concerning the sample’s engagement in online groups. The table below demonstrates the result from our T-Test analysis, showing the difference between the means of the two groups to be statistically significant. In other words, it is supportive of our initial hypothesis that joining an online group has a direct influence on the tendency to both believe and share fake news.

| [Dependent Variables] Response to fake news | [Independent Variables] Membership in a support group for a candidate or political party on social media | N | Mean | S.D. | t-test for Equality of Means | Sig. (2-tailed) |

| a. believability | (1) Yes (2) No | 357 868 | 3.34 3.14 | 1.21 0.98 | 2.84 | 0.005* |

| b. shareability | (1) Yes (2) No | 357 868 | 3.31 2.82 | 1.25 1.19 | 6.29 | 0.000* |

* Significant at level p < 0.01

Furthermore, the box plot shown below also indicates a significant difference in the likelihood of believing and sharing fake news among the two groups of respondents, since the mean value for the believability of fake news was higher for the “YES” group (members) compared to the “NO” group (non-members). The averages were 3.34 and 3.14, respectively. Correspondingly, the average shareability of fake news among the members was also considerably higher than that of the non-members, with average values of 3.31 and 2.82 respectively.

Box plot diagram: The distribution of the believability and shareability of fake news score, classified by group membership

In summary, the data analysis corroborated our hypothesis about information sharing in online groups: There is indeed something significantly different between the behaviour of members and of non-members; it appears that being a member of an online group can make one more susceptible to both believing and sharing fake news. Since the questions that we used to construct the variables in the analysis asked specifically about individuals’ membership to an online group supporting a political party or candidate, we can also infer that the impact of believability and shareability of false information here can potentially affect one’s electoral behaviour too. However, it is also imperative to note that there are at least two key constraints intrinsic to the data used in this analysis. One, the nature of the survey questionnaires only allows us to scratch the surface of the dynamics of information sharing in online groups. A deeper study is needed for a better understanding of the taxonomy of contents that are being shared in these online communities (i.e., what types of content shared). Through this survey alone, we cannot deterministically infer that dis/misinformation are more prevalent in online pages and groups; thus, making their members more susceptible to fake news. Rather, we can only say that there is something about being a member to online political communities which one can associate with an individual’s tendency to believe and share fake news. Two, the survey question did not ask about membership to a Facebook page and a Line group separately, inhibiting us from distinguishing the different nature of the platforms and their varying ability to monitor and moderate contents, albeit that there is anecdotal evidence suggesting that end-to-end encrypted messages can become a hotbed for disinformation propagation and a potential threat to electoral integrity.[3]

CONCLUSION: EXCLUSIVE COMMUNITIES, BIASES, AND TRIBALISM

Our interest in the effect of membership of online groups, especially political ones, is based on the premise that members can gain access to exclusive content that may not be publicly available to non-members. At the very least, subscribing to a political page or account will enable the person to gain “first access” to the content since most platforms’ algorithms tend to prioritize posts from inner circles such as friends, family members, and followed lists. Moreover, becoming a part of such an exclusive community can also serve as a heuristic cue that reinforces the sense of solidarity and belonging among members.

As our findings indicate, being a member of an online group is in fact associated with a stronger tendency to both believe and share fake news. We suggest that this could be due to two reasons: confirmation bias and tribalism. Online platforms tend to function as an “echo chamber” that perpetuates confirmation bias; that is a known global phenomenon. Individuals are likely to believe information that aligns well with their existing beliefs and ideology, thus, reinforcing the perceived credibility and veracity of the information. This concept, however, only partially explains the dynamics of information sharing wherein people share information that they believe in (e.g., high level of believability).

But what leads people to share information that they know is false, especially in the member-only settings? We suggest that tribalism can be one explanation. Once a person joins an online group, subscribing to an exclusive community, they feel that they gain access to things that they would otherwise not have access to; and to some, this even serves as a badge of privilege. This membership thus comes with social costs, and deviating from the constructed norms of the “tribe” may lead to negative consequences. A study of Lawson, Anand and Hakkar in the context of Indian netizens found that group members who do not conform to the behaviours of other group members by sharing the information propagated within the group can be subjected to reduced social interaction over time.[4] So, it is also possible that a group member will share fake news despite having doubts about the veracity, for fear of losing access to future information shared within the group.

Using the concepts of biases and tribalism allows us to move beyond focusing on the direct impact of content on behaviours. In the final analysis, it may not be the regular exposure to false contents per se that contributes to one’s susceptibility to fake news, but rather it is the venue in which they are shared which strengthens that tendency.

REFERENCES

- Clegg, N. How Meta Is Planning for Elections in 2024. Meta https://about.fb.com/news/2023/11/how-meta-is-planning-for-elections-in-2024/ (2023).

- TikTok. TikTok’s Stance on Political Ads. https://www.tiktok.com/creators/creator-portal/en-us/community-guidelines-and-safety/tiktoks-stance-on-political-ads/ (2024).

- O’Carroll, L. & Milmo, D. Musk ditches X’s election integrity team ahead of key votes around world. The Guardian (2023).

- M. Asher, L., Shikhar, A. & Hemant, H. Tribalism and Tribulations: The Social Costs of Not Sharing Fake News. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 152, 611–631 (2023).

- Prachathai. ‘Royalist Marketplace’ geo-blocked in Thailand, unblocked an hour later. Prachathai English (2023).

- Hicken, A. & Sinpeng, A. Thai Political Survey. (2023).

- Halpern, Daniel Valenzuela, S., Katz, J. & Miranda, J. P. From Belief in Conspiracy Theories to Trust in Others: Which Factors Influence Exposure, Believing and Sharing Fake News. In Social Computing and Social Media. Design, Human Behavior and Analytics (ed. Meiselwitz, G.) (Springer, 2019).

- Sriyai, S. The Postings of My Father: Tradeoff Between Privacy and Misinformation. Fulcrum https://fulcrum.sg/the-postings-of-my-father-tradeoff-between-privacy-and-misinformation/ (2023).

ENDNOTES

For endnotes, please refer to the original pdf document.

| ISEAS Perspective is published electronically by: ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute 30 Heng Mui Keng Terrace Singapore 119614 Main Tel: (65) 6778 0955 Main Fax: (65) 6778 1735 Get Involved with ISEAS. Please click here: /support/get-involved-with-iseas/ | ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute accepts no responsibility for facts presented and views expressed. Responsibility rests exclusively with the individual author or authors. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form without permission. © Copyright is held by the author or authors of each article. | Editorial Chairman: Choi Shing Kwok Editorial Advisor: Tan Chin Tiong Editorial Committee: Terence Chong, Cassey Lee, Norshahril Saat, and Hoang Thi Ha Managing Editor: Ooi Kee Beng Editors: William Choong, Lee Poh Onn, Lee Sue-Ann, and Ng Kah Meng Comments are welcome and may be sent to the author(s). |

2024/11 “The Cultural Power of Chinese Herbal Medicine Resulting from the Southeast Asian Belt and Road Corridors” by Khun Eng Kuah

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

- This paper explores the use of Chinese herbal medicine (TCM) as cultural power along the Southeast Asian Belt and Road corridors. It examines both the Mainland Chinese state and the Diaspora Chinese TCM corporations in utilising Chinese herbal medicine to exert influence on each other.

- The Mainland Chinese state expanded TCM into Southeast Asia (SEA) through a series of strategies, including setting up its flagship TCM corporation, the Beijing Tongrentang in SEA countries, establishing joint ventures with SEA Diaspora Chinese TCM corporations and offering joint TCM programmes in educational institutions.

- TCM companies in SEA not only offer herbal products and medication to the local population but also to Mainland Chinese tourists who buy these products in bulk due to the latter’s superior quality.

- TCM as cultural power goes both ways and is tapped upon by different players, not only for instrumental purposes but also to facilitate prospects for collaboration.

* Khun Eng Kuah is a former Visiting Senior Fellow at ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute. She is Distinguished Professor at the School of International Studies/Academy of Overseas Chinese Studies, Jinan University (Guangzhou, China) and Adjunct Professor, Department of Chinese Studies, National University of Singapore. The author is grateful to the Collaborative Center for the Promotion of Chinese Culture in Hong Kong, Macau, Taiwan, and Overseas, Jinan University for partial funding of this project.

ISEAS Perspective 2024/11, 14 February 2024

INTRODUCTION

This paper[1] seeks to demonstrate, using the case of Chinese herbal medicine (TCM), that ‘cultural power’ works multi-dimensionally. While Mainland China may use TCM as soft power to further its socioeconomic interaction with Southeast Asia, the Diaspora Chinese TCM corporations, in turn, extend their presence and influence on Mainland Chinese TCM consumption patterns through the superior quality of their products. This study solely focuses on the two way exchange of TCM products.

In 2013, President Xi Jinping launched the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) as part of China’s economic strategy to expand and widen China’s economic sphere of influence.[2] It specifically targeted six economic corridors that are within its reach of friendly influence. These are (a) New Eurasia Land Bridge Corridor; (b) China-Mongolia-Russia Economic Corridor; (c) China-Central Asia-West Asia Economic Corridor; (d) China-Pakistan Economic Corridor; (e) Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar Economic Corridor; and (f) China-Indochina Peninsula Economic Corridor. The focus of this monumental project is for China to become involved in the port, transportation lines and infrastructure development of these countries. Throughout Central Asia and Central Europe, within the Indian sub-continent to Africa, and in Southeast Asia, a flurry of activities has impacted the macro and micro-economy of those affected by BRI.

Table 1: Export Markets of China’s TCM Products by Regions

| Export Market | Export Quantity (‘000) | Export Amount (‘000 US$) | Export Quantity (%) | Export Amount (%) |

| Asia | 185.4 | 971430.70 | 82.95 | 85.28 |

| Europe | 18.6 | 91020.19 | 8.32 | 7.99 |

| North America | 9.6 | 48970.65 | 4.30 | 4.30 |

| Africa | 7.4 | 13370.16 | 3.31 | 1.17 |

| Asia Pacific | 1.2 | 9320.69 | 0.54 | 0.82 |

| Latin America | 1.3 | 5000.73 | 0.58 | 0.44 |

| Global Total | 223.5 | 1139140.13 | 100 | 100 |

Source: Adapted from 2016 Report on the Developmental Flow of Chinese Herbal Medicine, Department of Market Order, Ministry of Commerce, p.8; and Khun Eng Kuah. 2021. “Traditional Chinese Herbal Medicine as Cultural Power along the Southeast Asian Belt and Road Corridor”. Asian Journal of Social Science 49: 230.

Aside from this, there is also a focus on investments and the types of goods and services that China wishes to import from and export out of these countries. To expand TCM as an important export, the Chinese government targeted countries along the BRI corridors, especially the China-Indochina Peninsular Economic Corridor, commonly known as the BRI Southeast Asian Corridor, where half the ethnic Chinese population residing outside China lives. In December 2016, the State Council formulated the White Paper for China’s Traditional Chinese Medicine; this was followed by the National People’s Congress Standing Committee promulgating the Chinese Medicine Law and the Ministry of Commerce announcing the National Drug Circulation Industry Development Plan (2016−2020).[3] Firstly, it is estimated that the global consumption of TCM will reach USD 50 billion dollars in the years to come,[4] TCM is a lucrative venture for China, which is the biggest producer of such medicinal products and herbs. Asia is the biggest importer of TCM herbs and products and in 2017, it received 85% of the total Mainland Chinese TCM exports. Of the 85%, 54% was exported to ASEAN countries. There was also a 54% increase in export to Southeast Asia, South Asia and the Middle East at the same time, totalling US$760 million.[5]

Secondly, TCM is regarded as an important component of soft power for China to compete as an important humanitarian player in developing nations along the Belt and Road corridors. A report by Xinhua News agency titled “Xinhua Headlines: Traditional Chinese Medicine Gaining Popularity in Africa Amid COVID-19 Outbreak”, revealed that Chinese medical teams have seen a surge in patients seeking TCM treatment and consumption of TCM products to treat Covid-19 infections since early 2020.[6] Another Xinhua News agency reported that “Xinhua Headlines: Traditional Chinese Medicine Aids Global Fights Against COVID-19”. This amply demonstrates that in addition to ‘mask diplomacy’, TCM also became part of the geopolitical contest during the COVID-19 pandemic in countries, especially in Africa and Asia.

Apart from the sale of TCM products, China has also been pushing for the transmission of TCM knowledge through partnerships with various TCM colleges and universities. To name a few, Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman in Malaysia, and Nanyang Technological University and Singapore College of TCM in Singapore, now offer TCM courses at certificate, diploma and degree levels to train local TCM practitioners.[7] In this respect, China has the advantage of producing well-developed TCM training programmes to offer to educational institutions in Southeast Asia and other parts of the world.

Furthermore, Beijing’s flagship TCM corporation Beijing Tongrentang (同仁堂) has been aggressively opening up branches throughout the Asia-Pacific, including 4 branches in the already crowded TCM market in Singapore and 3 branches in Kuala Lumpur, and partnering Hai-O, which has 54 branches for the distribution of its TCM products and herbs.[8] In Indonesia and Thailand, there are standalone Beijing Tongrentang shops selling its products in local TCM shops. In Vietnam, it functions as a joint venture. In Australia, there are 9 integrated Tongrentang stores-clinics in the major cities of Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane, Perth and Cairns.[9] These Tongrentang stores-clinics compete with the local TCM stores for customers and patients. In Singapore and Malaysia, the local ethnic Chinese customers patronize their familiar local TCM stores for TCM products and herbs; likewise, they go to their familiar TCM physicians for treatment purposes. Some of the larger TCM clinics hire mainland Chinese TCM physicians to remedy the shortage of locally-trained TCM physicians.

SOUTHEAST ASIAN KNOWLEDGE OF TCM AND CULTURAL POWER

Southeast Asia houses around 30 million of the 60 million global Diaspora Chinese, and many of them regard TCM as an important alternative treatment for health and illness. There are many TCM halls that sell traditional Chinese herbs and herbal drinks, in addition to the numerous TCM clinics. This attests to the continued importance of TCM within the Diaspora Chinese universe. In fact, 85.5% of China’s TCM products are exported to Asia, including Southeast Asia. In 2017, the export share of TCM and herbal products to ASEAN countries was around 34%.[10]

Traditionally, TCM products have been consumed regularly in Southeast Asia, and countries such as Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia, the Philippines and Thailand have many local established TCM institutions that offer TCM training programmes. Their TCM corporations and factories produce and package TCM products and treatments according to the needs of the local communities. At the same time, they have expanded into the global market.

Especially in Singapore and Malaysia, there are several big local companies such as Eu Yan Sang and Hai-O Group which specialise in traditional Chinese medicine, Chinese herbs, as well as herb-based health supplements. Eu Yan Sang also produces globally sought-after Chinese herb-based health supplements and medicated oil. They also specifically produce a range of women-oriented products catering to menstruation, pregnancy and post-natal treatment.[11] In recent years, Eu Yan Sang expanded globally and into Mainland China, but there has been less success in the latter case, given the stringent Mainland Chinese laws with regards to pharmaceutical products. Nevertheless, the company is scaling up its presence in China.[12] Other TCM companies expanding in the Singapore market include ZTP, established in 1997 and now has at least 40 retail outlets,[13] and Wong Yiu Nam Medical Hall, an old brand TCM company that was first established in 1935 in Singapore. Wong Yiu Nam was acquired in 2009 by the Taiwanese healthcare group, Ma Kuang Healthcare Group. It continues to provide TCM products and herbs to the local population and also tourists as well as patients of the Ma Kuang TCM clinics in Singapore. Ma Kuang TCM clinics are also found in China and Taiwan.[14]

These Singapore and Malaysian brands of medicated oils, Chinese herbal products and herbal health supplements have attracted the attention of Southeast Asian Chinese as well as other ethnic groups, and Mainland Chinese who travel to Singapore buy large quantities of these products. Singapore and Malaysian produced brands of medicated oil and ointment such as Tiger Balm ointment, Axe Brand Universal Oil, Eagle Brand medicated oil and Hoe Hin White Flower embrocation (commonly known as Pak Fah Yeow or White Flower Oil), are well sought after and used by the Diaspora Chinese globally and by Mainland Chinese. Mainland Chinese can purchase these products online and the prices of some of these products are sometimes higher than for similar items produced in Mainland China. For example, the famous Singapore brand Tiger Balm costs at least 20-30% more in Mainland China. Why Mainland Chinese flock to Singapore and Malaysia for their supplements is because the products made in Southeast Asia are subjected to excellent quality controls. Additionally, their ingredients are clearly and accurately spelt out. The standard of service of the staff is also better than on the mainland. Thus, irrespective of whether it is in Chinatown, neighbourhood shops and at the airport, it is not uncommon to see Mainland Chinese purchasing Chinese medicated oil, herbal products and supplements in large quantities.

Although TCM as an alternative treatment for health and illness remains a niche product within the Diaspora Chinese communities, it is increasingly seen, accepted and used by select groups of people of different ethnicities who favour natural products and naturopathy; in Africa, these are considered a cheaper health alternative. In recent years, governments of some African countries have entered into agreements with Mainland China on the development of TCM in the African countries. However, many TCM products use animal parts; this has led to Mainland Chinese pharmaceutical companies sourcing animal parts and products in Africa and endangering wildlife and threatening some species to extinction in the process.[15]

CONCLUSION

Chinese herbal medicine is well-established among the Diaspora Chinese and Mainland Chinese. This provides the Chinese government with a way to exercise soft power and to further its influence along the Southeast Asian Belt and Road corridors. This is seen in TCM’s rapid expansion into this region through joint ventures and through the setting up of its TCM flagship Beijing Tongrentang corporation. However, it is not a one-way traffic; Southeast Asian nations such as Singapore and Malaysia are taking big steps in consolidating their hold on TCM exports and using it as reverse soft power to export to the Mainland Chinese market. The superior quality and the trust enjoyed by Singapore and Malaysian brands of TCM products including medicated oils continue to make them well sought after by Mainland Chinese. Hence, in studying TCM as cultural power, it is important to note that cultural power is not a one-way process. It is a multilateral process where the players involved are actively engaging with each other, and exploring ways to benefit themselves and each other.

ENDNOTES

For endnotes, please refer to the original pdf document.

| ISEAS Perspective is published electronically by: ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute 30 Heng Mui Keng Terrace Singapore 119614 Main Tel: (65) 6778 0955 Main Fax: (65) 6778 1735 Get Involved with ISEAS. Please click here: /support/get-involved-with-iseas/ | ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute accepts no responsibility for facts presented and views expressed. Responsibility rests exclusively with the individual author or authors. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form without permission. © Copyright is held by the author or authors of each article. | Editorial Chairman: Choi Shing Kwok Editorial Advisor: Tan Chin Tiong Editorial Committee: Terence Chong, Cassey Lee, Norshahril Saat, and Hoang Thi Ha Managing Editor: Ooi Kee Beng Editors: William Choong, Lee Poh Onn, Lee Sue-Ann, and Ng Kah Meng Comments are welcome and may be sent to the author(s). |

“Enhancing ASEAN’s Role in Critical Mineral Supply Chains” by Sharon Seah and Mirza Sadaqat Huda

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

• The clean energy transition momentum is gathering pace globally, and in Southeast Asia as well. The transition is dependent on an uninterrupted supply of critical minerals and metals that are essential for the production of low-carbon technologies.

• The supply of critical minerals is impeded by several constraints. First is the dominance of a handful of countries in both the upstream and downstream parts of the supply chain. Second is the current geopolitical race to secure supplies leading to greater protectionist behaviours, exhibited through export bans and trade impediments.

• This study focuses on four selected critical minerals which are important to the region. Two criteria are used in determining a mineral having high significance: (1) There are significant deposits of it which can be tapped on to bolster Southeast Asia’s strategic position in the supply chains; and (2) It is an essential input in industries and sectors of importance in Southeast Asia. The four critical minerals examined in this study are: copper, nickel, bauxite (alumina), and rare earth elements (REEs).

• The study makes three recommendations to enhance ASEAN’s role in the critical minerals supply chains. The first addresses the insufficiency of investments in early-stage exploration and exploitation of critical minerals and, in the process, calls for an embracing of circular economy principles. The second appeals for investments at all stages, including in technology to tap into downstream activities beyond refining and purification, and in the manufacturing of component parts such as battery cell storage and permanent magnets. The third calls for improvements in sustainability management in the mining sector, which is generally extremely environmentally and socially damaging to communities.

Trends in Southeast Asia 2024/3, February 2024

2024/10 “Vietnam-U.S. Security Cooperation Prospects under the Comprehensive Strategic Partnership” by Phan Xuan Dung and Hoai Vu

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

- In the past decade, Vietnam and the United States have incrementally strengthened security cooperation across various areas, including maritime security, defence sales, search and rescue, humanitarian and disaster relief, war legacy issues, and peacekeeping.

- Hanoi and Washington have pledged to enhance and broaden their security relations under the recently established comprehensive strategic partnership (CSP).

- Several conducive factors support the advancement of Vietnam-U.S. security cooperation in the upcoming years. These include growing strategic convergence, a deepening network of shared defence partners, and Vietnam’s military modernization efforts.

- However, sudden leaps or dramatic breakthroughs in Vietnam-U.S. security cooperation are unlikely due to certain constraints. These include Vietnam’s cautious approach, defence cooperation not being the top priority under the CSP, defence interoperability gaps, and lingering trust deficits.

- Therefore, despite the recent upgrade in diplomatic status, Vietnam-U.S. security cooperation has not reached a new level. Nonetheless, expanded defence collaboration in soft areas could help overcome some of the existing constraints and advance mutual strategic interests.

* Phan Xuan Dung is Research Officer in the Vietnam Studies Programme of the ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute. Hoai Vu is Research Assistant at the Institute for Foreign Policy and Strategic Studies under the Diplomatic Academy of Vietnam.

ISEAS Perspective 2024/10, 6 February 2024

INTRODUCTION

Since establishing a ‘comprehensive partnership’ in 2013, Vietnam and the United States have incrementally expanded their security relations, a domain that was hitherto sensitive and limited in scope. In 2015, the two countries adopted the Vietnam-U.S. Joint Vision Statement on Defence Cooperation, which codified activities already undertaken under the 2011 Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) on Advancing Bilateral Defence Cooperation.[1] Vietnam and the U.S. also engage in two dialogue mechanisms — the Political, Security, and Defence Dialogue and the Defence Policy Dialogue. Guided by these bilateral frameworks, Vietnam-U.S. security cooperation has progressed significantly across various areas, including maritime security, defence sales, search and rescue (SAR), humanitarian assistance and disaster relief (HADR), war legacy issues and peacekeeping.

Despite these remarkable strides, Vietnam-U.S. security cooperation remains at a low level, and primarily involves soft forms of engagement.[2] The recent upgrade of bilateral ties to a comprehensive strategic partnership (CSP) raises the question of whether this will change.

This article examines the recent progress in Vietnam-U.S. security cooperation and discusses its prospects under the CSP. It argues that given the current facilitators and constraints, the two countries will continue to advance defence collaboration at a measured pace, focusing on areas of low sensitivity.

RECENT PROGRESS IN VIETNAM-U.S. SECURITY COOPERATION

Maritime Security and Defence Articles

Maritime security and defence articles are key components in Vietnam-U.S. growing defence links. From 2017 to 2023, the U.S. State Department granted Vietnam approximately US$104 million in security assistance through the Foreign Military Financing (FMF) programme, aiming to bolster Vietnam’s maritime security and law enforcement capabilities.[3] Additionally, Vietnam received a separate US$81.5 million from FMF in 2018 as part of the U.S. Indo-Pacific Strategy.

A notable aspect of bilateral maritime security cooperation is U.S. port calls to Vietnam and joint naval exercises. After Vietnam opened the Cam Ranh Bay Military Port to all foreign naval vessels in 2010, the USNS Richard Byrd transport ship became the first to use the port’s logistical services in 2011.[4] Since then, U.S. ships have docked at the port for logistics and maintenance services almost every year. Three U.S. aircraft carriers — USS Carl Vison, USS Theodore Roosevelt, and USS Ronald Reagan — made port calls and held exchange activities in Vietnam in 2018, 2020 and 2023, respectively. Several U.S. naval vessels have visited Vietnamese ports and conducted non-combatant drills known as Naval Engagement Activity (NEA), with the Vietnam People’s Navy. The latest iteration of NEA, conducted in 2017, focused on diving, search and rescue operations, and undersea medicine.[5] Moreover, since 2016, Vietnam has participated in U.S.-led multilateral maritime exercises, including the Southeast Asian Maritime Law Enforcement Initiative (SEAMLE), the ASEAN-U.S. Maritime Exercise, and the Rim of the Pacific Exercise (RIMPAC).[6]

The U.S. fully lifted its lethal arms embargo on Vietnam in 2016, enabling Vietnam to procure U.S. equipment to modernize its military. From 2016 to 2021, the U.S. authorized the permanent export of more than US$29.8 million in defence articles to Vietnam.[7] The U.S. Defence Department’s active Foreign Military Sales with Vietnam has also surpassed US$118 million. Key U.S. arms transfer to Vietnam includes the handover of two decommissioned Hamilton-class cutters, currently the largest cutters in the Vietnam Coast Guard (VCG). In 2023, the U.S. promised the delivery of the third one,[8] making Vietnam and the Philippines the only countries to receive three U.S. Hamilton-class cutters (other recipients have received either one or two).[9] The U.S. has also supplied the VCG with six Boeing Insitu ScanEagle tactical drones and 24 Metal Shark patrol boats.[10] Additionally, Vietnam has bought 12 Beechcraft T-6 Texan II trainer planes as part of a package that comes with logistical and technical support.[11]

SAR and HADR

Given Vietnam’s vulnerability to natural disasters and climate change impacts, enhancing disaster preparedness and recovery capabilities is crucial. Thus, cooperation with the U.S. in SAR and HADR activities plays a vital role in augmenting Vietnam’s security. In 2014, the USS John S. McCain conducted a SAR exercise with the VPN off the coast of Da Nang as part of its NEA with Vietnam.[12] This marked the first SAR training activity between the two navies. Subsequent NEAs also included exercises on SAR and HADR. In 2016, the two countries signed a letter of intent to form a working group to explore the possibility of storing supplies in Vietnam for HADR purposes.[13] Vietnam has also participated in multilateral cooperation projects on HADR and joint HADR exercises under the Pacific Partnership and Pacific Angel engagements.

War Legacy Issues

Collaboration to address the consequences of the Vietnam War, including unexploded ordnance (UXO), Agent Orange, and soldiers missing in action (MIA), continues to serve as the foundation of Vietnam-U.S. defence relations. The U.S. has provided over US$230 million for UXO mitigation efforts in Vietnam.[14] In 2018, the two governments celebrated the completion of the six-year joint dioxin remediation project in Da Nang. A year later, joint cleanup efforts commenced at Bien Hoa Air Base, the largest remaining dioxin hotspot in Vietnam. The U.S. government’s financial contribution for this project currently stands at US$218 million, including US$90 million from the U.S. Defense Department.[15] In addition, as of 2023, the U.S. has provided US$139 million to fund health programmes that support Vietnamese with disabilities linked to Agent Orange exposure.[16] Regarding the search for American MIAs, as of June 2023, 151 unilateral and joint remains evacuation missions have been conducted, leading to the repatriation of the remains of 734 American soldiers.[17] In 2021, Washington officially began assisting Hanoi in identifying the remains of Vietnamese MIAs through a programme funded by the U.S. Defense Department.[18] Since then, the U.S. has provided Vietnam with more than 30 sets of documents related to Vietnamese MIAs, along with many war artifacts.[19]

Peacekeeping

In recent years, Vietnam has actively participated in United Nations peacekeeping missions, with support from several partners, including the U.S. In 2015, the two countries signed an MOU on peacekeeping, cementing their cooperation in experience sharing, personnel training, technical assistance, equipment, and infrastructure support.[20] Such cooperation lays the groundwork for future bilateral cooperation on peacekeeping missions. Under the Global Peace Operations Initiative (GPOI), the U.S. has spent US$10.87 million to support Vietnam’s peacekeeping contributions, including the deployment of a level-2 field hospital to the UN Mission to South Sudan in 2018.[21]

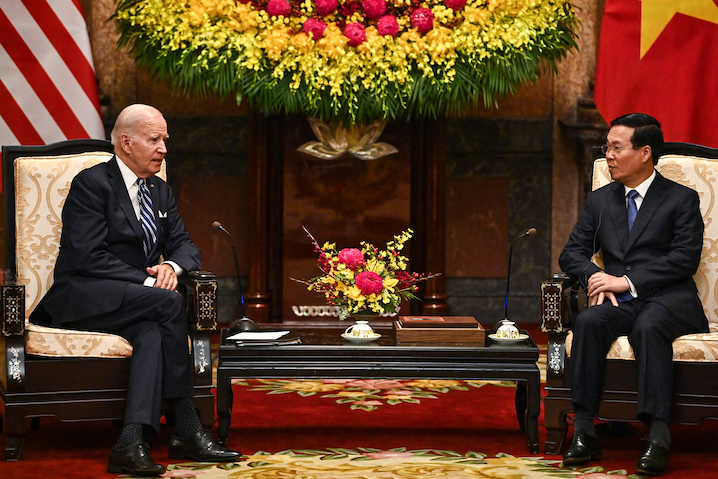

VIETNAM-US SECURITY COOPERATION UNDER THE CSP: FACILITATORS AND CONSTRAINTS

Over the past decade, Vietnam-U.S. security cooperation has witnessed substantial growth under the comprehensive partnership. This positive trajectory is expected to continue under the CSP established during President Joe Biden’s visit to Hanoi in September 2023. The joint leaders’ statement on the Vietnam-U.S. CSP reaffirms continued cooperation on maritime security, SAR, HADR, war legacy issues, and peacekeeping operations.[22] On defence industry and trade cooperation, the statement underscores the U.S. commitment to assist Vietnam in developing self-reliant defence capabilities. A new development is the establishment of a Law Enforcement and Security Dialogue between relevant law enforcement, security, and intelligence agencies.[23]

This section discusses the facilitators and constraints that will shape Vietnam-U.S. security cooperation under the CSP in the upcoming years.

Facilitators

First, the two countries share growing strategic convergence, aligning on key bilateral and regional security issues. As stated in the joint statement on the CSP, the U.S. supports a strong, independent, self-reliant, and prosperous Vietnam in safeguarding its sovereignty and territorial integrity.[24] Regionally, the U.S. envisions a unified and robust ASEAN where Vietnam plays an active role in promoting the group’s centrality in addressing regional security issues. The joint statement also reiterates the two countries’ mutual interests in promoting freedom of navigation and upholding international law in the South China Sea. Moreover, the importance of Vietnam’s geostrategic position in the U.S. Indo-Pacific strategy has been increasingly stressed by U.S. officials and U.S. national security documents.[25] This underscores Washington’s commitment to work with Hanoi in promoting a shared vision of regional security.

Second, Vietnam-U.S. security cooperation stands to benefit from a deepening network of shared defence partners. Vietnam has been strengthening bilateral ties with key U.S. allies and partners in Asia, many of which are its comprehensive strategic partners (India, Japan, South Korea) or soon-to-be comprehensive strategic partners (Australia,[26] Indonesia,[27] Singapore,[28] and Thailand[29]). In 2022, ASEAN also upgraded its relations with the U.S. to a CSP, paving the way for new maritime and defence initiatives.[30] These developments position Vietnam and the U.S. to expand the scope of their defence cooperation, particularly on maritime security and peacekeeping, under trilateral, quadrilateral, and multilateral frameworks.[31]

Third, Vietnam’s military modernization efforts present opportunities for further collaboration on defence articles and technology. After the 13th Party Congress in 2021, Vietnam approved a plan to build a streamlined and strong army by 2025 and a revolutionary, regular, elite, and modern army by 2030.[32] Vietnam has also strived to diversify its arms imports and boost domestic defence production capabilities to become more self-sufficient. The U.S. is recognized as a key partner in these efforts. This was made evident in the presence of several major American defence firms at Vietnam’s first international defence expo in December 2022. U.S. Ambassador to Vietnam, Marc Knapper, said that the event “represents a new stage in Vietnam’s efforts to globalize, diversify, and modernize, and the United States wants to be part of it.”[33] Indeed, following the expo, Lockheed Martin, Boeing, Raytheon, and Textron reportedly held discussions with top Vietnamese government officials regarding the possible sales of helicopters and drones to Vietnam.[34]

Constraints

Despite these conducive factors, sudden leaps or dramatic breakthroughs in Vietnam-U.S. security cooperation are unlikely due to several constraints.

The first is Vietnam’s cautious approach to deepening ties with the U.S. in order to avoid negative reactions from China. Despite concerns over China’s maritime ambitions, Hanoi prioritises maintaining a stable and peaceful relationship with its northern neighbour. China might feel threatened by bolstered Vietnam-U.S. defence ties and respond with punitive actions against Vietnam. Thus, Hanoi has made efforts to reassure Beijing that its CSP with Washington is not an anti-China security pact. During recent Vietnam-China high-level meetings that occurred around the upgrade, Vietnamese leaders repeatedly reaffirmed positive bilateral ties with China and Vietnam’s ‘four nos’ defence policy.[35] Notably, Vietnam hosted President Xi Jinping in December 2023, just three months after Biden’s visit. On this occasion, Vietnam elevated ties with China by establishing a “community of a shared future”,[36] seemingly to balance the upgrade with the U.S.

Given its sensitivities to rising tension between the two great powers, Vietnam might scale back on joint naval activities and military training with the U.S. to keep a low profile. This could explain why Vietnam cancelled 15 defence engagement activities with the U.S. in 2019[37] and did not participate in RIMPAC in 2022, despite having participated in 2018.[38] Vietnam will also be hesitant to engage in combat military exercises with the U.S. in the South China Sea.

A second related constraint is that defence cooperation is not the top priority under the CSP. In the joint statement on CSP, economic and technological cooperation are clearly the main focus, while defence and security ties receive less attention. Moreover, the statement leans towards non-traditional security issues that the two countries have already been collaborating on.

This makes sense as Vietnam’s primary motivation for seeking a CSP with the U.S. was not defence needs. The upgrade aligned with Vietnam’s desire to create a robust and diverse network of strategic partners to ensure three key long-term objectives — security, prosperity, and international status. While the U.S. is seen as an important partner in all three aspects, Vietnam currently emphasizes economic development goals.[39] Hence, for Vietnam, the CSP is more about economics than defence and security.[40]

Washington initially expected that a strategic partnership with Hanoi would result in stronger bilateral defence ties to counter Beijing’s maritime ambitions. However, leading up to the establishment of the CSP, the U.S. had progressively understood that Vietnam would not be comfortable with making the CSP all about defence and security. In various official and unofficial exchanges, U.S. officials and scholars recognized Vietnam’s delicate approach, as well as the need for more patience on the U.S. side.[41]

The third constraint are the defence interoperability gaps between Vietnamese and American forces. A major obstacle is the language barrier. Proficiency in English is still a challenge for the Vietnamese military, and few American personnel can speak Vietnamese.[42] Another obstacle is the low level of cooperation on defence sales, exemplified by Vietnam’s limited import of U.S. weapons. Some scholars have suggested that Vietnam could elevate bilateral defence ties with the U.S. by concluding large-scale arms deals.[43] However, since the lifting of the U.S. arms embargo in 2016, no such deal has transpired. The U.S. is reportedly in talks with Vietnam on the possible sale of F-16 fighter jets.[44] Vietnam has yet to confirm this information, and the deal might not materialize. In the past, Vietnam has shown reluctance to buy major U.S. weapons, such as a second-hand F-16 fighter jet and a P-3C Orion maritime patrol aircraft.[45] Hanoi worried that purchasing major offensive weapons from the U.S. could irk Beijing, especially after the high-profile CSP upgrade. Moreover, there are interoperability concerns over Vietnam’s limited capacity to acquire and integrate U.S. military technology. These include high costs, a steep learning curve, and incompatibility with Russian-made equipment, which currently forms the majority of Vietnam’s weapon systems.[46]

Last but not least, trust deficits between the two countries remain. Despite the increased U.S. recognition of Vietnam’s one-party state system, political differences could still impede defence cooperation. In particular, Hanoi fears that the U.S. Congress might reject equipment sales due to concerns over human rights conditions in Vietnam.[47] Divergent stances on the Russian-Ukraine war, along with Vietnam’s continued reliance on Russia for major arms supplies, also hinder greater strategic trust. Vietnam is cognizant of potential sanctions under the U.S. Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act for buying Russian weapons.[48] Finally, Hanoi has reasons to doubt Washington’s commitments to the region in the upcoming years, given the U.S. ongoing preoccupation with conflicts in Europe and the Middle East.

CONCLUSION

Despite the recent upgrade in diplomatic status, Vietnam-U.S. security cooperation has not reached a new level. Instead, bilateral military relations will continue to concentrate on areas of low sensitivity, including maritime law enforcement, SAR, HADR, war legacy issues, and peacekeeping. Nonetheless, expanding collaboration in these fields could mitigate some of the existing constraints in Vietnam-U.S. defence ties and advance mutual strategic interests.

The US should provide more funding and equipment for Vietnam to enhance its self-reliant defence capabilities, as stated in the CSP. However, it is imperative that the U.S. consider Vietnam’s post-upgrade sensitivities and refrain from pushing for large-scale arms trade that could alarm China. The priority should be to help Vietnam modernize the VCG and improve its maritime domain awareness through equipment transfers and technical assistance. This serves the mutual interests of both countries by promoting freedom of navigation and upholding international law in the South China Sea.

In addition, boosting education and training for Vietnamese military officers will help bridge interoperability gaps between US and Vietnamese military forces. This could include more opportunities for Vietnamese officers to join English language training programmes and study in U.S. institutions. The U.S. should also invite Vietnam to join more non-combat bilateral and multilateral naval exercises. This will foster professional and operational relations between the two countries and with other defence partners.

Finally, increased U.S. efforts to address Agent Orange and UXO, as well as assisting Vietnam in the search for its MIAs, can play an important role in reducing trust deficits. Vietnamese leaders have consistently indicated that greater U.S. efforts to address war consequences are a prerequisite for bilateral cooperation in other areas.[49]

ENDNOTES

For endnotes, please refer to the original pdf document.

| ISEAS Perspective is published electronically by: ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute 30 Heng Mui Keng Terrace Singapore 119614 Main Tel: (65) 6778 0955 Main Fax: (65) 6778 1735 Get Involved with ISEAS. Please click here: /support/get-involved-with-iseas/ | ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute accepts no responsibility for facts presented and views expressed. Responsibility rests exclusively with the individual author or authors. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form without permission. © Copyright is held by the author or authors of each article. | Editorial Chairman: Choi Shing Kwok Editorial Advisor: Tan Chin Tiong Editorial Committee: Terence Chong, Cassey Lee, Norshahril Saat, and Hoang Thi Ha Managing Editor: Ooi Kee Beng Editors: William Choong, Lee Poh Onn, Lee Sue-Ann, and Ng Kah Meng Comments are welcome and may be sent to the author(s). |

2024/9 “Advancing the ASEAN Outlook on the Indo-Pacific Beyond Indonesia’s Chairmanship” by Joanne Lin

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

- Indonesia’s Chairmanship in 2023 has advanced the AOIP’s implementation through tangible projects and activities, thereby elevating the AOIP as a pivotal platform for promoting ASEAN’s central role.

- Beyond Indonesia’s Chairmanship, ASEAN needs to prioritise a consistent and impactful implementation of the AOIP across successive Chairmanships. This is essential to solidify the AOIP’s standing as a strategic document to reinforce ASEAN’s central role in the region.

- To advance the AOIP and ensure its ongoing strategic relevance, ASEAN can adopt some key strategies. These include assuming a leadership role in implementation, formulating a multi-year work plan, maintaining a commitment to quality-focused approaches, transforming bilateral activities into regional projects, and establishing a dedicated fund.

- While the AOIP alone may not fully address escalating strategic competition, leveraging ASEAN-led mechanisms for its implementation positions the organisation as a “bridge-builder”. This role allows ASEAN to actively contribute to inclusive multilateral solutions, and foster dialogue and cooperation among regional powers.

* Joanne Lin is Co-coordinator of the ASEAN Studies Centre at ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute, and Lead Researcher (Political-Security) at the Centre.

ISEAS Perspective 2024/9, 2 February 2024

INTRODUCTION

ASEAN embraced the ASEAN Outlook on the Indo-Pacific (AOIP)[1] in 2019 as a strategic response to escalating geopolitical tensions[2] and the growing influence of major powers in the region. The Outlook reflects ASEAN’s commitment to maintaining its centrality and leading role in the region by promoting its mechanisms and adhering to key principles such as inclusivity, openness, and a rules-based framework.

Specifically, the Outlook aims to foster practical and tangible cooperation with ASEAN’s external partners in four key areas: maritime cooperation, economic, connectivity, and sustainable development. Despite Indonesia’s advocacy and support from ASEAN’s dialogue partners, the initial implementation faced criticism for its sluggish progress and perceived lack of concrete initiatives during the first four years.

Apart from discussions and sporadic activities[3] with dialogue partners, there was no course of action for the implementation of the AOIP until November 2022, when ASEAN leaders adopted the Declaration on Mainstreaming Four Priority Areas of The ASEAN Outlook on The Indo-Pacific within ASEAN-Led Mechanisms.[4] The declaration acknowledged the need for collective leadership with ASEAN to proactively address emerging challenges in the region. It also endorsed a List of Criteria on Mainstreaming the AOIP (an internal document) to implement the four priority areas of the AOIP through ASEAN-led mechanisms such as the ASEAN Plus-One, ASEAN Plus Three (APT), East Asia Summit (EAS), the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF) and the ASEAN Defence Ministers’ Meeting Plus (ADMM-Plus).

This development helped set the stage for Indonesia’s Chairmanship in 2023 to advance AOIP’s implementation through tangible projects and activities. A notable achievement was the inaugural ASEAN Indo-Pacific Forum in September 2023[5] focusing on green infrastructure and resilient supply chains, sustainable and innovative financing, digital transformation and the creative economy. The Forum brought together ASEAN member states and external partners and reportedly identified 93 cooperation projects worth US$38.2 billion, with an additional 73 potential projects amounting to US$17.8 billion.[6]

For the first time since the AOIP’s adoption, the initiative seems to yield tangible benefits to the region, attracting new commitments by ASEAN’s external partners. As a result, regional leaders increasingly recognise the AOIP as a pivotal platform for promoting ASEAN’s central role and mechanisms.[7] The initiative has also been praised by Singapore Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong, who commended it for being “omnidirectional and inclusive”.[8]

Despite the success of the Forum, questions linger regarding the AOIP’s effectiveness in shaping the regional architecture as well as in addressing current and future geostrategic challenges. There are also uncertainties in the prospect of advancing the AOIP beyond Indonesia’s Chairmanship. This Perspective addresses these questions and explores potential strategies for ASEAN to ensure the continued relevance and successful implementation of the AOIP across all chairmanships.

ASSESSING THE IMPACT AND LIMITATIONS OF THE AOIP

Despite its lack of a strategic dimension, the AOIP has been deemed successful in securing buy-ins from ASEAN’s external partners, mainly owing to its mild and apolitical nature, and for focusing on cooperation rather than rivalry.[9] The document’s neutrality (which differs from most Indo-Pacific strategies) makes it possible for most countries to accept the AOIP’s values and cooperation.

The overwhelming support from ASEAN’s dialogue and external partners, including China (a target of various Indo-Pacific strategies) has led to an increasing recognition of the AOIP’s benefits by more ASEAN countries. Currently, seven dialogue partners, namely India, Japan, the US, Australia, China, the Republic of Korea (ROK) and New Zealand have issued standalone statements with ASEAN regarding AOIP cooperation. While Canada and the EU have not issued separate statements, they have incorporated similar language in joint leaders’ statements with ASEAN. This has therefore enabled ASEAN to be a norm-setter and to play a leading role in the Indo-Pacific.

Beyond dialogue partners, most other external partners of ASEAN have committed to various forms of concrete cooperation across AOIP’s priority areas, enhancing the prospects for sustained implementation and for more partners in the long run.

While the AOIP has increased ASEAN’s standing in the regional architecture through the support of external partners, its strategic impact in addressing or mitigating the negative consequences of major power strategic competition in the region remains in question.

Despite garnering support from ASEAN’s partners, the AOIP’s lack of a strategic thrust hampers its ability to effectively manage external threats, particularly those posed by China. The inclusive nature of the AOIP makes it challenging for ASEAN to be viewed as a “like-minded” partner by countries that have a vested interest in the Indo-Pacific, such as the US, Japan, Australia and India (QUAD members), as well as countries such as the ROK, UK, Canada, France and Germany. This is especially so when ASEAN refuses to speak out against China for its aggression in regional flashpoints such as the South China Sea and the Taiwan Strait.

Essentially, the AOIP’s limited strategic perspective and its absence of a hard power component constrain its efficacy in addressing conflicts. Apart from preventive diplomacy, it is unable to deter security threats or provide a strategic balance[10] in the region. This has prompted Indonesia’s former Foreign Minister Marty Natalegawa to claim that the AOIP was more of a defensive and programmatic approach than a bold one seeking to actively confront geopolitical challenges.[11]

The proliferation of non-ASEAN security groupings like the QUAD and AUKUS demonstrate that ASEAN-led initiatives such as the AOIP may not adequately meet the region’s security needs. Opinion polls, as reflected in surveys like the State of Southeast Asia Survey reports,[12] suggest that major powers’ security initiatives may weaken ASEAN’s centrality, despite their rhetorical support for the AOIP and ASEAN centrality.

Although there is increasing interest for ASEAN to take on a greater responsibility in managing major power rivalries, the region is far from being a provider of regional security.[13] Notwithstanding the AOIP being created to address geostrategic tensions, the defence sector, in particular, has been hesitant to adopt the Indo-Pacific concept. The ASEAN Defence Ministers’ Meeting (ADMM) has only recently adopted a concept paper on the implementation of the AOIP from a defence perspective,[14] four years after the AOIP was published. Moreover, despite the expansive scope of maritime cooperation, the ADMM can only approve one AOIP activity each year and the activity should be one-off and informal in nature – signalling a lack of enthusiasm to mainstream the AOIP in the defence sector.

As such, under Indonesia’s leadership, the AOIP’s implementation has focused on softer cooperation and easier objectives like green infrastructure, digital developments, sustainable development, and the promotion of trade and investment.

This has led some observers to argue that the AOIP primarily symbolises the group’s aspirations rather than offering a concrete pathway to achieve specific outcomes.[15] Therefore, the Outlook may only be sufficient to kickstart and support more processes, dialogues, and lower-hanging cooperation rather than achieving tangible strategic outcomes, particularly those pertaining to security.

AOIP’S IMPLEMENTATION BEYOND INDONESIA’S CHAIRMANSHIP

The significant advancement of the AOIP’s implementation in 2023 was not surprising. Indonesia’s fervent push for extensive implementation was notably in line with President Joko Widodo’s priority of establishing the country as a Global Maritime Fulcrum. However, the enthusiasm for the AOIP’s continued progress beyond Indonesia’s Chairmanship remains uncertain.

During the early stages of formulating this Outlook, ASEAN countries were not unified in their perspectives on the narratives surrounding the Indo-Pacific or their level of support for the concept.[16] As such, despite the ultimate endorsement of the AOIP by all ASEAN countries, one of the significant challenges in its implementation is the varying degree of ownership among the member countries, along with their willingness and ability to allocate resources for its implementation.

Encouragingly, the AOIP is gradually becoming internalised within ASEAN as an instrument that brings tangible benefits to the grouping. As noted in the ASEAN Leaders’ Declaration on ASEAN As an Epicentrum of Growth[17] adopted in September 2023, ASEAN leaders have committed to further efforts in operationalising the AOIP by expediting AOIP projects and activities initiated by ASEAN or jointly with external partners, and to support the list of concrete projects identified at the inaugural ASEAN-Indo-Pacific Forum[18].

The Foreign Minister of Laos as the Chair of ASEAN in 2024 has given the reassurance that Laos will continue the implementation of ASEAN’s initiatives, including the AOIP.[19] Similar to Indonesia’s priorities in 2023, it is expected that Laos will strengthen the connectivity and sustainable development aspects of the AOIP by focusing on integrating and connecting economies, digital transformation, and climate change resilience.[20] Additionally, the Secretary-General of ASEAN Kao Kim Hourn has expressed hope that Laos might consider convening the 2nd ASEAN-Indo-Pacific Forum this year, with a theme that is in line with Laos’ Chairmanship priorities.

Importantly, Indonesia’s efforts in pushing for the mainstreaming of the AOIP has resulted in some level of institutionalisation through the creation of processes such as the “List of Criteria on Mainstreaming the AOIP”. Systematic processes have been put in place to identify, evaluate, track and monitor programmes, projects and activities under the AOIP undertaken by the ASEAN Secretariat. This form of tracking is expected to persist across Chairmanships, irrespective of the levels of motivation and aspiration that each Chair may have towards the Indo-Pacific and the Outlook. Overall, these developments suggest a growing recognition of the AOIP’s significance within ASEAN.

POTENTIAL STRATEGIES IN ADVANCING THE AOIP

In advancing the implementation of the AOIP, ASEAN may consider the following strategies. Firstly, a multi-year work plan encompassing a list of activities is crucial for maintaining a consistent trajectory of progress and ensuring a more impactful implementation. While external partners may propose recommendations for joint activities, ASEAN should also assess its own needs to prioritise specific areas of cooperation to align with frameworks such as the ASEAN Maritime Outlook (AMO),[21] which can offer a clearer direction for ASEAN’s maritime efforts in the Indo-Pacific.[22]

Secondly, to reinforce ASEAN centrality, the grouping should take the lead in proposing programmes and projects under the AOIP that will contribute to ASEAN community building and meet sectoral bodies’ priorities. ASEAN should identify the most appropriate partners to implement specific projects based on the strength of each country. ASEAN should also ensure synergies in the activities across ASEAN-led mechanisms. This approach will prevent overlaps in activities or workshops proposed by external partners for a more streamlined implementation.

Thirdly, the identification of AOIP initiatives should involve meaningful efforts rather than a mere re-packaging of existing cooperation under various Plans of Action. ASEAN should focus on innovative initiatives that can enhance AOIP’s strategic value across ASEAN-led mechanisms including the EAS, ADMM-Plus, and the ARF, prioritising quality over quantity. Quantity-focused approaches may lead to competition among dialogue partners and undermine the strategic essence of the AOIP. ASEAN should shift its focus from an obsession with numbers or statistics to activities that yield not only output but meaningful outcomes that can increase its members’ capabilities in a strategic competition.

Fourthly, although ASEAN has identified an extensive list of concrete projects, predominantly of a bilateral nature, as seen at the inaugural ASEAN-Indo-Pacific Forum, there is a crucial need to transform these isolated initiatives into cohesive ASEAN strategic objectives. The transformation can be achieved through the process of “connecting the connectivities”[23] or fostering collaboration and knowledge-sharing among member states to produce innovative projects. Moving forward, a concerted effort should be made to ensure that AOIP projects or activities deliver benefits to as many ASEAN member states as possible, thereby solidifying their status as true “ASEAN” initiatives.

Lastly, there is a pressing need to establish a dedicated fund to implement AOIP activities. This will allow ASEAN to rely more on internal funding for its neutrality and centrality, and to assert more control over its priorities. While cooperation with external partners should persist, having an independent funding mechanism will let ASEAN determine the nature and execution of projects. Furthermore, this will ease the burden of the current and future Chairs in organising larger-scale events such as the ASEAN-Indo-Pacific Forum, and provide more incentives for them to host more such activities.

CONCLUSION

The AOIP has experienced significant success during the Indonesia Chairmanship. However, achieving consistent and impactful implementation of the AOIP across successive Chairmanships is imperative to solidify the Outlook as a strategic document that can bolster ASEAN’s central role. The analysis above highlights crucial factors for ensuring AOIP’s success, emphasising the importance of ASEAN’s leadership, developing a multi-year work plan, ensuring commitment to quality-focused approaches, transforming bilateral activities into regional projects, and establishing a dedicated fund. These will not only foster a sustained momentum in advancing the AOIP but also ensure its strategic relevance.

The analysis also underscores that relying solely on the AOIP may prove inadequate in addressing the rising strategic competition and the multitudes of initiatives led by major powers. However, leveraging ASEAN-led mechanisms, particularly the EAS (the region’s premier leaders-led forum) in the implementation of the AOIP, has the potential to position ASEAN as a pivotal “bridge-builder”. Secretary-General of the United Nations Antonio Guterres has emphasised ASEAN’s crucial role in ‘building bridges of understanding’ and advancing multilateral solutions.[24] This approach empowers ASEAN to facilitate extensive dialogue among regional powers and foster interactions between countries like China and the US. Furthermore, it allows ASEAN to actively contribute to shaping guiding principles and norms, advocating for multilateralism, and working towards a more inclusive regional architecture.

ENDNOTES

For endnotes, please refer to the original pdf document.

| ISEAS Perspective is published electronically by: ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute 30 Heng Mui Keng Terrace Singapore 119614 Main Tel: (65) 6778 0955 Main Fax: (65) 6778 1735 Get Involved with ISEAS. Please click here: /support/get-involved-with-iseas/ | ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute accepts no responsibility for facts presented and views expressed. Responsibility rests exclusively with the individual author or authors. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form without permission. © Copyright is held by the author or authors of each article. | Editorial Chairman: Choi Shing Kwok Editorial Advisor: Tan Chin Tiong Editorial Committee: Terence Chong, Cassey Lee, Norshahril Saat, and Hoang Thi Ha Managing Editor: Ooi Kee Beng Editors: William Choong, Lee Poh Onn, Lee Sue-Ann, and Ng Kah Meng Comments are welcome and may be sent to the author(s). |

Temasek Working Paper No. 7: 2024 – The Changing Fortunes of the Raja Negara and the Orang Laut of Singapore in the 18th Century by Benjamin J.Q. Khoo

2024/8 “Understanding Indonesia’s 2024 Presidential Elections: A New Polarisation Evolving” by Max Lane

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

- The coalition developing around the candidacy of Prabowo shows characteristics of being a regrouping of core elements from Suharto’s New Order. Incumbent President Joko Widodo is also supporting this coalition. One of Widodo’s sons is Prabowo’s vice-presidential running mate.

- While polls put Prabowo in the lead, scoring in the mid-40 percentages, support for him may nevertheless be stagnating.

- A polarisation is developing between this coalition and the other parties, especially the PDI-P, and some elements of civil society, especially the liberal media and students. This polarisation is connected to tensions between modes of politics: one strongly influenced by Suharto era cronyism and one connected to those disadvantaged for being outside that elite.

- A differentiation between an approach emphasising policy discussion and one emphasising rhetorical image-making has become sharper. This is paralleled by stronger criticism by the two other candidates, Anies Baswedan and Ganjar Pranowo, of Prabowo’s support for Widodo’s dynasty-building manoeuvres, his accumulation of wealth, and alleged mismanagement of the defence equipment procurement.

- As this polarisation is still in its early stages, it is not clear how significant it will be in the thinking of Indonesia’s 200 million voters. But while it develops, there is increasing potential for collaboration between the Baswedan and Pranowo camps, and more support from civil society for them.

ISEAS Perspective 2024/8, 31 January 2024

*Max Lane is Visiting Senior Fellow at ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute. He is the author of “An Introduction to the Politics of the Indonesian Union Movement” (ISEAS 2019) and the editor of “Continuity and Change after Indonesia’s Reforms: Contributions to an Ongoing Assessment” (ISEAS 2019). His newest book is “Indonesia Out of Exile: How Pramoedya’s Buru Quartet Killed a Dictatorship” (Penguin Random House, 2022).

INTRODUCTION

According to almost all recent polls, Indonesia’s Defence Minister Prabowo. Prabowo is the leading presidential candidate, scoring always over 40%[1] for “electability”. He has the support of the incumbent President, Joko Widodo, whose eldest son is Prabowo’s vice-presidential candidate and whose youngest son is chairperson of the fanatically pro-Prabowo Indonesian Solidarity Party (PSI). Prabowo also has the support of former two-term president Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, and prominent New Order military figure General Wiranto. There is also a kind of blessing from well-known members of the Suharto family, with Prabowo elevating his former wife, Titiek Suharto, to vice-chair of his party Gerindra’s Advisory Board.[2]

What is surprising is that despite all the support, his poll results less than a month out from the election on 14 February are considerably lower than those of candidate Widodo in the lead-up to the 2019 presidential election. At that time, Widodo was polling at over 50% with his opponent then, Prabowo, at 33%.[3] Today, even with Widodo’s and Yudhoyono’s ostensible support, Prabowo is scoring around 43%, up only 10% from 2019.

A NEW DIFFERENTIATION OR EVEN POLARISATION IN THE ELITE

The 20-year period after the fall of President Abdurrahman Wahid has been characterised by the theatre of rhetorical polarisation among the Indonesian political elite. Although there is still some time left for campaigning, the contestation between the three presidential candidates – Baswedan, Prabowo and Pranowo – is revealing new cleavages which may reframe Indonesia’s political life. On the other hand, a consensus over the fundamentals of the status quo, as defined by government policies of the last ten years, may see a relapse into the politics of unanimity.

There are two types of political differentiation being revealed in the current electoral process.

The first relates to the nature of the coalition formed in support of Prabowo. As indicated above, this coalition comprises many elements associated with the New Order. Apart from Prabowo, Yudhoyono and Wiranto, there is also former Coordinating Minister Luhut Panjaitan, Widodo’s business partner since at least 2008.[4] Another is General Moeldoko, former Commander of the Armed Forces between 2013-2015, who Widodo appointed his Chief of Staff. Also appearing is long-term Golkar figure and oligarch, Aburizal Bakrie, the Mentor of Prabowo’s campaign team. While Widodo successfully portrayed himself in 2013-2014 as a novelty from outside the New Order elite, this image was belied by his immediate appointment of Luhut as a de facto ‘prime minister’, who was assigned more than 14 crucial policy implementation tasks.[5] This was followed later by Widodo’s rapid appointment of Moeldoko as his Chief of Staff and then his total rapprochement with Prabowo. Prabowo further indicated the process of Widodo’s integration into this milieu. His association with figures from Suharto’s New Order was further emphasised when Golkar recently posted an AI-generated video of the long-dead Suharto speaking for the Prabowo campaign.[6]

While there are also big business supporters of both the Anies Baswedan and Ganjar Pranowo candidatures,[7] this combination of ex-generals, Golkar figures and the Suharto family exposes Prabowo’s coalition as harking back to the Suharto era’s New Order. There is even talk of Prabowo and Titiek Suharto remarrying to bring a Suharto back into the presidential palace.[8] The Baswedan coalition and the Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (PDI-P) both receive support from business figures who came into prominence during the New Order. Baswedan is supported by former Golkar figure and oligarch businessman, Surya Paloh. However, it can be argued that the latter supporters do not represent core New Order elements in the way that Prabowo’s coalition does.

The PDI-P itself, under the leadership of chairperson and former president Megawati Sukarnoputri, had opposed Suharto when he was moving towards a dynastic approach to politics. Suharto’s government intervened in the internal affairs of Megawati’s party to stop her from becoming its leader, and in 1998 Suharto appointed his daughter, Tutut, to the Cabinet in a clear attempt to pave the way for a dynastic succession.[9] For ten years, during the two presidential terms of Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, the PDI-P was outside of government. The party is not based on or embedded in cronyism with the oligarchs at the level of national government. During the two terms of Widodo’s presidency, Widodo prioritised positions for his own cronies, especially Luhut Panjaitan but also others such as the academic, Pratikno. In the process, PDI-P has been kept out of the most important business-linked ministries.[10]

Baswedan, as a politician and an academic prior to that, has not been embedded in any party or other institution. He courted the Democrat Party (PD) in 2013, then the PDI-P during Widodo’s 2014 campaign, and was nominated by the Justice and Welfare Party (PKS) and Gerindra when he stood for Governor of Jakarta in 2017, prior to being supported by the National Democratic Party (Nasdem) and the National Awakening Party (PKB), as well as the PKS for his presidential campaign now. This is the history of an ambitious politician, but one not embedded within the core of the elite coming out of the New Order.

This new polarisation between core New Order elite elements, now including Joko Widodo, and those outside has meant that the polarisation is creating concern beyond the political parties, among some elements of civil society. This is most visible in sections of the media – led by the liberal TEMPO magazine[11] – as well as human rights NGOs and students opposing the Prabowo-Gibran Rakabuming Raka (read: Widodo) camp. There are two reasons for these concerns. First is the use of Widodo’s incumbency to build a dynasty for his family, and second is the displayed impunity (Prabowo’s) for past human rights violations. The liberal media has led in expressing these worries, but in early January 2024, the first signs appeared of what may well become a student protest movement.[12]